| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XV Number 6. . . .November 7, 2008

excerpt:

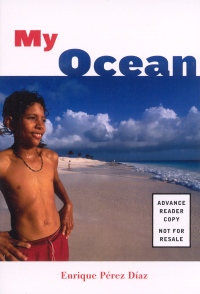

My Ocean, by Enrique Pérez Díaz, is the story of a boy trying to make sense of Cuban/American political relations as he grows up in Cuba and experiences their tangible results affecting every aspect of his life and family. In a narrative best suited to 9 to 12-year-olds, "Kiki" describes his life to "his" ocean, ostensibly writing letters to float away in bottles. By turns adoring and accusing, pleading and praising, Kiki addresses this inanimate body and brings to life his own emotionally fortifying relationship with the ocean, as well as its fraught role in enabling Cubans to escape to "El Norte," the United States to Cuba's north. This sophisticated framing technique and impressive attempt to grapple with a political situation that becomes extraordinarily complicated when it intersects with the daily lives of average people, such as Kiki and his family, ultimately falls short with a lackluster narrative. Diaz points out in his Author's Note that the events in My Ocean "attempt to give an overview of life in Cuba throughout the past fifty years." Perhaps the scope here is too ambitious; whatever the reason, the narrative is episodic rather than focused around a clear plot. Urgent issues such as whether Kiki and his mother should—philosophically and morally— join his grandparents in El Norte, and whether they can—legally, financially, and physically—do so become dulled in a plethora of daily trivia. While there is a clear attempt on Diaz's part to provide a well-rounded portrayal of real life as experienced by the average Cuban, ultimately his choice of narrative strategy is unsuccessful. Diary and epistolary formats are notoriously difficult to control, not least because of the challenges they present in conveying active scenes. This is precisely the failing point of My Ocean: Kiki's disjointed, scattered musings on his life are primarily conveyed in dull flashbacks and lack the strength to carry forward his story as a more traditional, climax-driven structure would have. In short, despite the compelling aspects of his situation, the way Kiki's story is told ultimately prevents the growth of readers' empathy.

Recommended with reservations. Michelle Superle teaches Children's Literature, Composition, and Creative Writing at the University of the Fraser Valley.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- November 7, 2008.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |