| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XIV Number 18. . . .May 2, 2008

|

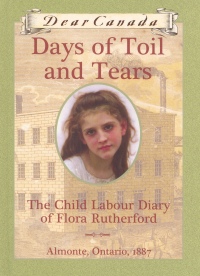

Days of Toil and Tears: The Child Labour Diary of Flora Rutherford. (Dear Canada).

Sarah Ellis.

Toronto, ON: Scholastic Canada, 2008.

219 pp., hardcover, $14.99.

ISBN 978-0-439-95594-2.

Subject Headings:

Child labor-Ontario-Almonte-Juvenile fiction.

Almonte (Ont.)-Juvenile fiction.

Grades 5-8 / Ages 10-13.

Review by Mary Thomas.

*** /4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

August 18 [1887]

Dear Papa and Mama,

Mr Longfellow is still thinking about the humbler poet.

Who, through long days of labour,

and nights devoid of ease,

Still heard in his soul the music

of wonderful melodies.

I wonder what the days of labour were? Maybe in a mill? and the nights devoid of ease? It makes me think of bad dreams. I don't tell Auntie or Uncle, but it is as though those machine teeth are waiting for me every night. In the day is is far far back in my mind, but I wish I had never seen Barney's arm with its awful pinkness. I must not be downhearted.

Now that I have eight verses of this poem by heart I can say it over and over again to the back ground of the spinning machine.

From our modern perspective, we think that nothing could be worse than working a 10-hour day in a woolen mill at the age of eleven. But for Flora, being rescued from an orphanage where she had been put when both her parents died of pleurisy (the reason why she writes her diary in the form of letters to them), going to live with her aunt and uncle is a wonderful escape and adventure. And working is a way she can contribute to her "family"'s finances.

The choice of the year 1887 is a good one as it was the year when a government commission was established to look into conditions in the mills in Ontario. Great excitement is generated at the mill where Flora and her aunt and uncle work, but there is also great apprehension on Flora's part. Since the legal working age is 14 and she is only 11, would the mill's owners be forced to let her go? She knows it would be wicked to lie about her age, but, on the other hand, she does not want to lose her job or get anyone else in trouble. Exercising some ingenuity, she escapes detection, but, because of a whistle-blower in the factory who complains to the members of the commission not about children being hired but about the toilet facilities among other things, she is fired the next week. In the year covered by the diary, Flora suffers a concussion from hitting her head on the underside of one of the looms (a mouse running over her legs while she was tying a broken thread startled her), and her uncle is badly injured, through no fault of his own, just as he was about to be promoted to a better—and better paying—job. Suddenly, a viable life style—hard, but definitely with its fun sides—becomes impossible.

One reads of the horrors of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and thinks complacently that this is all in the distant past, and besides it was never like that here in Canada. Flora's diary, set only 150 years ago, shatters those comfortable thoughts. Flora and her aunt and uncle do manage to make a future for themselves by going to British Columbia to work on another uncle's farm, but what if this uncle had not been available? An accelerating downward spiral of poverty and hopelessness, with Uncle James becoming more depressed and the two women more discouraged by the month, is about all that they could expect.

Young Flora is basically a cheerful soul who makes the best of whatever situation in which she finds herself, and she does not allow herself to become depressed or obsessed with the way things are that are not as she'd like them to be. She admits that it would be nice not to go to work every day, but, on the other hand, she is not really keen to be going to school instead. It is necessary, therefore, that the reader look behind the Sunday picnics and occasional special Saturday closings of the mill (to allow the workers to go to the circus, for example), to see the drudgery of six days of hard work from seven in the morning until six in the evening, with a half-hour for lunch and a couple of bathroom breaks. Add to this the constant danger of injury, including the inevitable loss of hearing (one woman says she really misses the sound of the birds!), and the very low wages, and you get 'toil and tears' indeed.

Luckily, the diary is imbued with Flora's sense of fun and the love of her aunt and uncle (and kitten); otherwise, it would make for a very grim read! Instead, it is a book full of people that it would have been a pleasure to know better who are making the best of a very hard life.

Recommended.

Mary Thomas feels that her job in an elementary school library in Winnipeg, MB, is far too pleasant to actually count as work, especially when measured against that of Flora, Auntie Janet, and Uncle James!

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 2, 2008.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |