| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XII Number 18 . . . .May 12, 2006

|

When I Was a Boy Neruda Called Me Policarpo: A Memoir.

Poli Délano. Illustrated by Manuel Monroy. Poems by Pablo Neruda. Translated by Sean Higgins.

Toronto, ON: Groundwood/House of Anansi, 2006.

84 pp., cloth, $17.95.

ISBN 0-88899-726-4.

Subject Headings:

Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973-Juvenile literature.

Délano, Poli-Childhood and youth-Juvenile literature.

Poets, Chilean-20th century-Biography-Juvenile literature.

Authors, Chilean-20th century-Biography-Juvenile literature.

Grades 4-7 / Ages 9-12.

Review by Lois Brymer.

*1/2 /4

Reviewed from Advance Reader Copy.

|

| |

|

excerpt:

Tía Delia was still sleeping, so I slipped into her room by myself to wish her a Merry Christmas, and to look at the old maps that covered the walls of the room.

As I went to give her a kiss on the cheek, El Niño came flying out from under the covers and sank his sharp fangs into my left leg, right under my knee.

I fell to the floor screaming in fear and pain. I felt as though my heart was trying to escape from my body.

My parents came running, and then Tío Pablo rushed in, his face covered in shaving cream.

“What’s going on?” he yelled.

The grownups tried to beat the badger off my leg—many of their kicks hitting me instead—and finally managed to separate the beast from my bloody, shredded leg.

Being bitten at eight years of age by El Niño, the “belligerent” yet adored pet badger of Nobel Laureate, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, is one of the childhood memories that Poli Délano remembers about the “things that happened in those days” when he and his parents lived for a while on an old estate near Mexico City with the “eccentric” poet and his wealthy Argentinian wife, Delia del Carril.

When I Was a Boy Neruda Called Me Policarpo is Poli Délano’s memoir of some very unusual adventures he had as a young boy with the fun-loving man he called “my Tío Pablo.” In recalling their experiences together, the author, whose real name is Enrique Délano Falcón, surmises that, because Neruda was a poet, “maybe that’s why he was given to doing odd things,” notably, buying an embalmed kangaroo and a skull small enough to have been a child’s; serving ants under the guise of caviar to his wife (also known as Tía Hormiguita which means “ant”); and taking all-day trips on Sundays to a town called Cuernavaca to eat iguana at Neruda’s favourite restaurant.

Délano, who still goes by “Policarpo” or “Poli,” the nickname that Neruda gave him before he was born, writes about growing up in the lavish and outlandish lifestyle that his parents and the Nerudas led as Chilean diplomats during the mid-1930s to mid-1940s. He remembers listening to adult conversations at parties and poetry readings about noted poets and how World War II was progressing; dancing to the music of marimba players; dropping in on friends of Tío Pablo, one in particular, a painter who had about fifty Pekinese dogs and served his guests juice made from the Jamaica flower; going someplace new every weekend with his Tío Pablo and Tía Delia to look at “weird junk” at the market; finding out that the “tastiest bit” of human flesh is the meaty part of the hand; and watching a spider fight (bets were made) between a “portentous walking stick” and a “pampered pet tarantula” named Renata.

Délano also reminisces about what he learned from his Tío Pablo especially about eating. Neruda, who had “pretty strange tastes” and a “fondness” for such exotic delicacies as bear meat, roasted goat and monkey, fish eggs, Chinese snakes, Japanese insects, and quail eggs suggested to his “Poli” that “it is good to try everything,” even fried worms and grasshoppers which Délano says he found disgusting, “but only a little.”

Although Tío Pablo taught him other fun things, for instance how to swim; how to catch bugs and insects; and how to look for flora and fauna in the sea, perhaps the most important lesson the author learned from his mentor was that not all children were as privileged as he was. In the final chapter entitled, “Like Taking a Bone from a Dog,” Délano talks about being bullied and getting beaten up by several boys for invading their territory when, wanting to earn some spending money to buy a fountain pen and a watch, he stole their idea of selling chewing gum in front of the local cinema and looking after the cars of theatre goers. He remembers Tío Pablo telling him, “If this had happened among gangsters, they would have killed you without a second thought” and then Tía Delia further explaining to him that the other boys were trying to make money out of necessity to support their families not to buy “possessions” as Délano had intended to do.

When I Was a Boy Neruda Called Me Policarpo is described on the dust jacket as Délano’s “charming memoir” of a “magical time.” While the author’s boyhood experiences seem to be extraordinary and memorable, and no doubt were magical for him, unfortunately the charm, magic, and Délano’s writing style (he is an award-winning author) do not shine through in Sean Higgins’ English translation. The language is stiff, formal, and unnatural. For example, when Tía Delia wears mismatched shoes and her husband asks her if she has lost her mind and she replies to him that her other pair of shoes is exactly the same, Délano informs readers, “It made me laugh so much, I had to excuse myself and go out to the patio.” Would an eight-or-nine-year-old boy say that?

As well as deficiencies in the translation, the memoir comes across as a superficial recounting of the comings and goings of Délano, his parents, and the Nerudas. This may be deliberate on the author’s part to simulate the simplicity of a child’s diary. However, if this is the case, it does not make for a page-turning, engaging, or attention-grabbing read.

Délano’s storytelling lacks depth, energy, and detail. Most important, there is no intimacy with the characters. Just when the author begins to draw his audience into his world - being bullied at boarding school; becoming mesmerized by the cliff divers in Acapulco; killing a snake with his new bow and arrow set; or watching his Tío Pablo get his head split open in a brawl with some Germans - he moves on to something else. He not only leaves readers up in the air, he never allows them to get too close to him, to his feelings, or to the action.

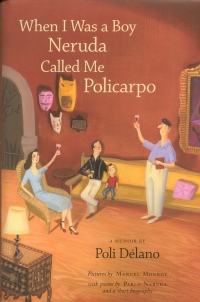

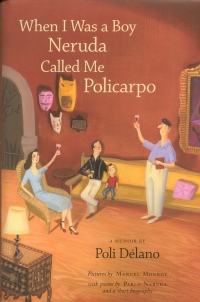

Visually the book has “pick up” appeal. The cover illustration, which looks like an acrylic painting, captures the “joie de vivre” of the characters with Délano as a boy sitting in the middle of his parents. Eyes are focused respectfully on and toasting a standing Pablo Neruda. All are oblivious to the mischievous badger, El Niño, who is in the background eating his way through a book and a rug. There is a playfulness to Mexican illustrator Manuel Monroy’s folk art style that reflects the intended spirit of the book and the characters’ lifestyle. Visually the book has “pick up” appeal. The cover illustration, which looks like an acrylic painting, captures the “joie de vivre” of the characters with Délano as a boy sitting in the middle of his parents. Eyes are focused respectfully on and toasting a standing Pablo Neruda. All are oblivious to the mischievous badger, El Niño, who is in the background eating his way through a book and a rug. There is a playfulness to Mexican illustrator Manuel Monroy’s folk art style that reflects the intended spirit of the book and the characters’ lifestyle.

The book is well-designed with an easy-to-follow layout that features a table of contents, a prologue, and seven chapters each introduced by a full-page illustration by Monroy. Six of Neruda’s poems are included throughout the memoir between chapters and are printed on taupe-shaded paper, a prominent colour in Monroy’s drawings. At the end of the book is a five-page biography and postage-stamp-sized black and white headshot of Neruda. The biographical note could have been more effective and certainly more apropos to the memoir had it been done as a photo essay that included pictures of the poet and Délano. In addition, a map of the many places the author talks about might have given non-Mexican readers a much clearer and better idea of the memoir setting.

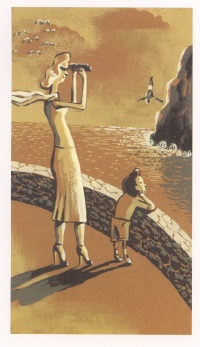

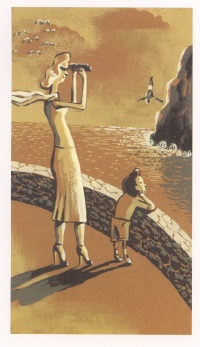

Manuel Monroy’s sepia-hued illustrations resemble the brownish-tinted photographs reminiscent of the 1930s and 1940s. Where the text fails to emit emotion, Monroy’s gentle and child-like images succeed in conveying the mood and theme of nostalgia, and the soft tones suggest the haze of the memory. Using line and shape, Monroy does a much better job than the author of connecting the reader to “Poli” whose fear, happiness, awe, excitement, disappointment, and enthusiasm can readily be seen in his face and body language. Monroy creates each scene at “Poli’s” eye-level and from his perspective as a small boy experiencing life in an adult world that is much bigger than he is. No other children appear in the illustrations perhaps because the text makes mere mention of Délano’s friends.

Neruda’s poems, with the exception "Poetry," are too sophisticated for the book’s recommended nine-to-twelve age group. Even Délano says that he didn’t understand Neruda’s poetry; but he does say that he liked how the poems sounded. "Poetry," translated by Alistair Reid, might be an excellent introduction to Neruda’s work and an inspiration for those children who have ever thought about writing poetry. Here is the first verse - simple, beautiful, and understandable:

And it was at that age.....poetry arrived

in search of me. I don’t know, I don’t where

it came from, from winter or a river.

I don’t know how or when,

no, there weren’t voices, they were not

words, nor silence,

but from a street it called me,

from the branches of the night,

abruptly from the others,

among raging fires

or returning alone,

there it was, without a face,

and it touched me.

Overall, it is doubtful that Délano’s memoir has enough appeal to hold the interest of, or to make the cultural connection with the publisher’s intended North American young audience. One wonders if Délano wrote this book for children in the first place. Is the voice of “Poli” that of a young Chilean boy sharing his experiences with other children, or is it the adult voice of Délano remembering his boyhood adventures? When I Was a Boy Neruda Called Me Policarpo seems to be a trip down memory lane for “baby boomers” who can reminisce with the author about cowboy and Indian movies and the news reels that preceded them, Roy Rogers and his horse Trigger, the Lone Ranger, Tarzan, Adams gum, Scheaffer fountain pens, and Omega watches. Children who have or have had a special relationship with a grown up may relate to “Poli,” and perhaps they may think his adventures with his Tío Pablo were neat and cool. However, they never have a chance to be part of “Poli’s” life and sadly, in the end, they are left out.

Not recommended.

Lois Brymer is a former publicist and recent graduate of the University of British Columbia’s Master of Arts in Children’s Literature Program.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 12, 2006.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

Visually the book has “pick up” appeal. The cover illustration, which looks like an acrylic painting, captures the “joie de vivre” of the characters with Délano as a boy sitting in the middle of his parents. Eyes are focused respectfully on and toasting a standing Pablo Neruda. All are oblivious to the mischievous badger, El Niño, who is in the background eating his way through a book and a rug. There is a playfulness to Mexican illustrator Manuel Monroy’s folk art style that reflects the intended spirit of the book and the characters’ lifestyle.

Visually the book has “pick up” appeal. The cover illustration, which looks like an acrylic painting, captures the “joie de vivre” of the characters with Délano as a boy sitting in the middle of his parents. Eyes are focused respectfully on and toasting a standing Pablo Neruda. All are oblivious to the mischievous badger, El Niño, who is in the background eating his way through a book and a rug. There is a playfulness to Mexican illustrator Manuel Monroy’s folk art style that reflects the intended spirit of the book and the characters’ lifestyle.