| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XII Number 10 . . . .January 20, 2006

excerpt:

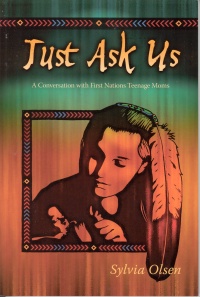

Heather's First Nations relatives accepted Yetsa, but remained shocked that she had become pregnant: being half-white did not make her immune from the "Indian girl with the baby" stereotype. Heather's non-Aboriginal relatives saw her pregnancy as a typical outcome of her being Aboriginal. And, regardless of who they were, everyone wondered about what Olsen and Heather were going to do with the situation, and what would be best for both the young mother and her child. Those are the questions which are faced by all teen parents and their own parents, but Olsen saw this family crisis as an opportunity to explore a social and cultural phenomenon, to seek answers to crucial questions, and to offer an opportunity for all involved to discuss, share, and seek solutions. The outcome is Just Ask Us, an interesting combination of action research and authentic personal story-telling. With funding from the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, the project was undertaken in 2003. Thirteen young mothers, ranging in ages from 15 through 24, participated both in formal discussions (focus groups and directed interviews) and informal, community-strengthening events (picnics, birthday parties, baby showers), building relationships and camaraderie. Several young men also took part in the project, but it is the voices of women which dominate the conversation. Adding to the conversation are the voices of community members, elders, grandparents, social and health support workers. It is truly a rich and revealing discussion, although Olsen also points out that "there were things they didn't want to talk about. Sexual abuse and violence were two subjects acknowledged but generally avoided." Each chapter begins with a fictionalized vignette (based on a combination of real stories, blended to maintain anonymity), followed by text which explores and discusses a series of issues. "What's the Problem?" offers an historical and cultural context, and "Who We Really Are" explores the stereotype of First Nations teen mothers, making it clear that, in so many ways, they are teens like any other in Canada. "We Need to Understand" why sex education, as currently presented, doesn't work for this audience while "Sex Changes Everything" and "Condoms and Complications" focus on the difficulty that teens have with responsible sexual decision-making, and the reasons why condom use is frequently ineffective. Once a young woman finds herself pregnant, abortion is rarely considered, and the reason is this: "Because we don't look down on people who have babies. We accept babies, no matter what." Culturally - irrespective of traditional or Western religious affiliation - abortion is not accepted as an option amongst First Nations communities in the same way that it is outside First Nations communities. "Being Pregnant" takes the reader through the minefield of emotions faced as a young woman works through denial, having to tell and deal with the responses of family members and her boyfriend, and then, to live with the irrevocable changes pregnancy brings: weight gain, giving up smoking and alcohol, disinterest or abandonment by the baby's father. These young women are suddenly thrust into roles, responsibilities, and situations for which they are unprepared. In "We're Adults and Parents," we read of their broken dreams, difficulties or delays in completing their education, conflicts with their own parents and family members as to how to raise their children, and overwhelming, their sense of frustration and disappointment at hopes that are dashed and dreams that are now denied, at least for the present. And they do have hopes and dreams because, even though they are dealing with adult responsibilities, they also insist "We're Still Teenagers." Being a teen has its own set of challenges; being teen mothers, they find themselves stressed by the demands of an infant, continually having to deal money shortages, having conflicts with their own parents (who themselves unprepared to be grandparents), losing friendships with their peer group, and running into difficulties with or ending the relationships with their baby's father. Olsen points out that the problems discussed in this chapter aren't unique to the young women of the study: "Teenage mothers face parental fears that are common to all mothers... But unlike older parents, they don't have the skills, experience, or education to deal with those fears." Still, many rise to the challenge and find within themselves strength and courage to make necessary life changes: "My baby straightened me up. Once I was a mom it made me think. School wasn't my main priority until after my son was born. That's when I really knew I had to graduate. I wanted to give him a better life than I had. I wanted him to have a mom that had a job." Highly Recommended. Joanne Peters is a teacher-librarian at Kelvin High School in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- January 20, 2006.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |