| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XI Number 9 . . . .January 7, 2005

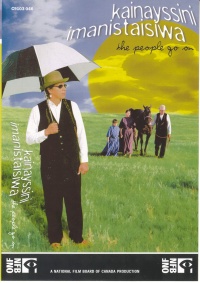

Kainayssini Imanistaisiwa: The People Go On is a film for adults, but young adults at college, university and in grades 11 and 12 would also appreciate it. The Kainai Blood Indians of southern Alberta live in sight of magnificent omnipresent mountains. Traditionally, these slopes and peaks have been incorporated into Kainai art, in a diamond or triangular pattern which Kainai have pointed out to personnel in faraway museums. The recent effort of the Kainai to find and retrieve their cultural artifacts was the catalyst which compelled writer/director Loretta Sarah Todd to make this film. The film opens with a young man, Josh One Horse, welcoming viewers to Standoff, home of the Blood Tribe. Josh takes us on a drive in his pick-up to the picturesque area where the sun dance is held, and he speaks of the influence of his grandparents who taught him about traditional ways. "We teenagers shouldn't be too cool to sit down with our elders," he says. Older spokespersons, in gorgeous natural settings, speak of the significance of the land which holds the memory of their people and is crucial to their culture. Leroy Little Bear describes the extensive area which the Blackfoot, of which Kainai Blood people are a part, call home. Louise Crop-Eared Wolf tells how, in 1877, Red Crow rejected the poor land offered him by the government of Canada, demanding a reserve "between the chief mountain and the valley buttes," where the bones of his ancestors were buried. "The land provides," says Narcisse Blood. "Birds and animals have the same need as we to survive." The survival of native people was in doubt in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, at least in the minds of white officialdom. Leroy Little Bear explains that the Aboriginal people trusted some of their sacred objects to white people because they believed initially that the white newcomers would become "one of us - adopted brothers and sisters." Meanwhile, back in Ottawa, the government believed that the natives would be extinct or assimilated within three generations. There was a rush by anthropologists to collect aboriginal clothing and other artifacts. "Missionaries, the church, the Indian agents were all change agents," he explains. The scenes in which Louis Soop of the Blood family met with Jonathan King of the British Museum in London are fascinating and moving. Soop was there to look at the artifacts in the Deanne Freeman collection. In the 1890s, Maude and Frederick G. Freeman, official food rationers for the government of Canada, collected a great many artifacts. In a poignant moment, Mr. Soop lights sweet grass and prays while King looks on. Later he notes that it had been a hundred years since anyone had prayed over the artifacts. King and Soop examine a robe dating from 1869. Decorated in figures of humans and of horses in distinctive, vivid, Blackfoot-Blood colours, it tells a story that the elders would be best able to interpret. "Why don't I just take this back with me?" Mr. Soop says, only half in jest. Sadly, Mr. Blood takes back only a photograph. Some of these artifacts travelled on loan to the Gait Museum in Lethbridge as "The Ancestors' Exhibit." After elders closely examined the items, they were attractively displayed according to tradition. A young visitor commented, "It's sad. All the things they owned are shut in these little cases and their families can't have them." Several band members, including Louise Crop-Eared Wolf, spoke of white culture's misidentification of such artifacts. In a Spokane museum, Ms. Wolf saw an exhibit showing a man holding a medicine bundle, when, in fact, they were always held by women. Of the Freeman exhibit, Narcisse Blood says, "It's not we who need to understand." To him, the display was good in that it educated white people about the original people whose land they now inhabit. He spoke of future plans to recover all such items to be preserved in a museum on the reservation. Since the 1970s, attempts have been made to repatriate medicine bundles, which are spiritual bundles made up of material items in which birds and animals have significance. "We look for ceremonial items first," Mr. Blood explains. In his travels to recover lost treasures, he has encountered a variety of receptions. "In some cases, friendships form," he says, "and relationships are what we're all about." Fred Weasel Head described his emotions when bringing home medicine bundles from the Smithsonian Institution. As the women carried the sacred bundles out of the building, he felt nervous, as if the institution might change its mind. Six bundles had to be left behind, and, when he left, it was almost as if he could hear children crying. Back home, his wife hung their family's bundle over the bed; it had been taken away in 1924. That night, Mr. Head sensed something moving around in the house. A door opened and shut, but no one visible was there. He believes the sounds came from a spirit emerging and going outside to look around its home. All of the people who appear on screen to tell of their experiences are compelling, but several other aspects of the movie didn't work for this reviewer. Two actors, a man and a woman in early 20th century costume, appeared, sometimes leading a horse across the plains, sometimes contrasted to a 21st century phenomenon, like a gas station. Obviously the writer/director intended them to show that past generations are ever-present in spirit. If the actors had worn clothing typical of the mid-19th century, their purpose would have been clearer. Mixing fictional characters with real people detracts from the power of the latter. To further emphasize that society is comprised, not only of those currently alive, but also of generations past and yet to come, black and white images from 19th century photographs appeared on banners and on TV sets lined up on the grass. These gimmicks were unnecessary. The young people examining the artifacts was a more interesting juxtaposition. Also, the device of asking tribe members, "Where were you two hundred years ago?" was unnecessary; the Kainai people were articulate without prompting. Their message will linger in viewers' minds for a long time. Highly Recommended. Ottawa's Ruth Olson Latta has a Master of Arts degree in History from Queen's University, Kingston, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- January 7, 2005.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |