| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XI Number 8 . . . . December 10, 2004

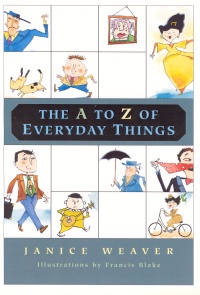

excerpt: Not everyone jumped right on the Gregorian calendar bandwagon, however. There's always great resistance whenever someone starts messing with time itself especially when that someone is a religious leader, not a scientist or even an elected official and many countries that were using the Julian calendar took hundreds of years to accept Pope Gregory's reforms. In Britain and her colonies, the Gregorian calendar was adopted only in 1752. By then, eleven days had to be dropped to bring everything back in line. People went to bed on September 2 that year and woke up the next morning on September 14, with many convinced that their lives had somehow been shortened by eleven days. Others took it all in stride, with one man jokingly complaining to the newspaper that though he seemed to have been dozing for more than a week, he felt he wasn't "any more refreshed than after a common night's sleep." Readers will find, when it comes to Janice Weaver's The A to Z of Everyday Things, that, although the book's publishers tailor it to the "10 and up" market, one size fits just about all. With exuberance and humor, Weaver traces the origins of twenty-six everyday things and shares how they have evolved over time. Accessorizing Weaver's fall line-up are the smart illustrations of Francis Blake. Capping it off is the beautiful cover design which sets varnished images against a matte background. The contrasting texture that results is analogous to appliqu‚ and appeals to the reader's sense of touch as well as sight. In the introduction, Weaver claims to have "filled this book with stories" about "extraordinary ordinary things." The language here is crucial. The author offers not stiff and starchy "explications" or "analyses," but the more relaxed "stories." Everybody likes a good yarn. By dressing down technology, Weaver renders it accessible to the young people who might not otherwise relate to it in its formal garb. Since Weaver esteems the alphabet as the most important invention ever, because by it we transmit vast quantities of knowledge across time and space, she patterns her book on it. That is, she devises one entry for each of the 26 letters of the Roman alphabet. Naturally, "A" is for "Alphabet." The book continues with "B" for "Black," "C" for "Calendars," "D" for "Diamonds," and so on. Whereas the average chapter length is four pages, those covering weightier topics (the alphabet, calendars, money, and zero) are one-and-a- half times as long. The author trims her book with an index and an extensive bibliographical list of print and online resources. From calendars and kissing to oaths and underwear, Weaver's catalogue includes an unusual and seemingly random assortment of items. Yet, the author has a knack for mixing and matching them in her fluid, non-linear style. All sorts of connections and cross-references exist within entries, the most obvious being "Black" which invokes comparisons to its binary opposite, "White" in chapter "W." Another such correlation involves "Rice," which shows up in the sidebar on "Chopsticks and Rice" under "Forks," and in the list of ingredients for the original "Ice Cream," as well as in a section of its own. Then, too, the first chapter links not only to "Numbers" in the middle of the book but also to the final chapter on "Zero": all three sections deal with the development of symbols to record information. The fact that the text often folds back in on itself in these ways contributes to the "extraordinariness" of the everyday things. Alongside the principal information, The A to Z of Everyday Things works into sidebars some otherwise loosely gathered threads. One type of sidebar centres text horizontally on the page, frames it with a double border and a heading, and introduces into the background a faint watermark of the pertinent letter of the alphabet. The other sort arranges text in small, gray- shaded boxes, without headings, set flush against the outer margins and full-page. Through these sidebars, readers learn facts such as that the Chinese word for computer comprises the symbols for "electric" and "brain," and that tulips, rather than necklaces, were choice adornments in 1630s Holland. Clearly, Blake's illustrations are the perfect accessories to pull together Weaver's textual wardrobe. The drawings that mark the start of each chapter are often amusing in their own right; they are funnier still as readers come to understand them within the context of the text. For instance, the introductory image for "L - Lipstick" depicts one laurel-wreathed, togaed man jealously eyeing another laurel-wreathed, togaed man's dark-hued, pursed lips. The illustration makes sense once a reader encounters the sidebar note that explains men in Ancient Rome wore different shades of lipstick to denote their social status. The illustration at "Y - Yawning" is comical because the one character stifles an enormous yawn as he turns away from two opera singers. The humor occurs on two levels, both occurrences due to pointed contrasts. First, all three of the characters' eyes are closed whereas their mouths are open. Despite those similarities, the singers appear enraptured by their own performances, while the yawner just appears bored. Second, the yawning character expresses what many people think (that opera is a drag) but refrain from saying for fear of being thought unsophisticated. As the illustrator's own website remarks, Blake's ink and watercolor pictures "can be darkly satirical or warm and personable, but [they] are always informed by a sharp wit" (www.francisblake.com/index.html). That same sharp wit informs the cover artwork, as well. The cover establishes visual continuity by repeating some of the images located at the beginnings of chapters. Yet this is repetition with a difference: the characters' postures and expressions are subject to change, even if only very subtly. For example, inside under "Queen's English" a surly-looking, sleep-deprived, wart-ridden Noah Webster figure clasps his dictionary tightly under his arm, with bookmarks that look suspiciously like anachronistic post-it notes sticking out at the edges. On the front cover, however, Webster props up his dictionary on a lectern, pointing to the word it has opened to: "bore." Additionally, the teddy bear on the front rests beside a suitcase labeled "Paris"; Teddy either has ditched, or has been ditched by, the human traveling companion we see him with in "H - Holidays." In any event, Blake's illustrations will appeal to readers precisely because they are dynamic rather than static -- that is, they "move." As for tone and examples, the author demonstrates with her choices that she has an excellent sense of her audience. Her tone is not too taut, nor too slack; instead, it is relaxed and conversational. Readers witness Weaver's wittiness when she writes of the reluctance of Western world to adopt the notion of zero. She comments that it was "a whole lot of fuss over nothing" (p. 102). Yet along with the humor, Weaver also conveys a sense of reverence for the rituals and traditions of the past that inform so many of our everyday things. Furthermore, Weaver makes use of up-to-date examples. For instance, she mentions the recent marketing campaigns to persuade women to purchase diamond rings for their right hands (p.18). In addition, when she remarks that soldiers in the Trojan War exhibited a passion for tabl‚ comparable to our culture's present-day obsession with high-tech electronic games, she drops Brad Pitt's name into the fray because of his role in the movie Troy (p. 29). Although the content tries to pass itself off as North American in scope, it demonstrates an unmistakable American bias. Indeed, the numerous references to the United States might get tiresome if it were not for the fact that so many of the commonplace American items originated in Greece, Rome, Italy, China, India, and England, and were either inherited or appropriated from those civilizations. At the same time, while this reviewer was pleased to see Weaver reference Canada with respect to "Diamonds," she was surprised that Canada's connection to "Tulips," which dates back to World War II, never materialized. After all, the annual National Tulip Festival in Ottawa ("The Tulip Capital of North America") originated with a gift of 100,000 tulip bulbs from the Dutch Royal Family (http://www.tulipfestival.ca/en/FestivalHistory/). Nevertheless, _The A to Z of Everyday Things_ demonstrates how multiple influences and perspectives hone, and thereby improve, ideas and inventions. At Cdn $12.99, The A to Z of Everyday Things offers sensible fashion at a discount price. This versatile book about ideas and inventions would make a good "hand-me-down" for nine-year- olds, yet would outfit early teens just as easily. In addition, the author is generous with the material so that no alterations are necessary for older readers. It is for the young and the young at heart anyone who wants to look smart. Hats off to Weaver and Blake for this, their second collaboration! Recommended. Julie Chychota has an M.A. in English, and is employed by the University of Manitoba and Red River College in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- December 10, 2004.

AUTHORS

| TITLES | MEDIA REVIEWS

| PROFILES

| BACK ISSUES

| SEARCH | CMARCHIVE

| HOME |