| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XI Number 20 . . . . June 10, 2005

excerpt:

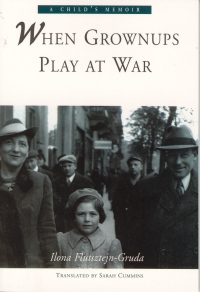

Such was the worry and the terror that nine-year old Ilona Flutsztejn-Gruda experienced in 1941 as she and her Jewish family fled the invasion of the Nazis into Lithuania. As a retired professor of chemistry at the University of Quebec, she has recorded her memories of World War II, which were published in French in 1999 and have now been translated. Originally from Poland, she and her parents survived the Holocaust by traveling east, staying in communal farms and villages, finally ending up in Uzbekistan. She details the struggle for daily survival, her personal difficulties as a child being repeatedly shifted to new situations, the pressures that threatened to tear her family apart, anti-Semitism and the tense political circumstances of the time. This makes for compelling reading. Little has been known until recent years about the Jews who escaped Hitler by moving eastward through Russia. They avoided death but nevertheless experienced the trauma of disruption, the fear of being caught, of being homeless and starving. Ilona experienced all of this, as well as periods of stability. In her travels, she saw the good and the bad in people. She was forced to adapt to different languages and cultures. Her education changed from one location to another. Separated for a time from her father, she helped her mother tend pigs and keep chickens. No matter the circumstances, children engage in play and seek out relationships. Ilona's relationships with other children and her parents are an important part of this memoir. An only child, she had an even greater need to find friends. Her cousin, Hala, was her greatest friend, and Ilona was devastated when Hala's family left for the United States. She relates her interactions with a variety of children, some of them good influences, some which gave her parents concern. These experiences were the school of life and made her much wiser than she would normally have been. An important part of the memoir is her observations on the operation of the socialist system in Russia. Although collectivization and rationing helped people survive, there were serious problems. Corruption meant that some people got more than others, from food to housing to positions. Fear and distrust led to many grave actions being taken against ordinary people. She recalls the confusion she and her mother, especially, felt at these events. Later, I wondered about this situation. Why did Polish Communists, most of whom were Jewish, show such scorn for those who weren't one of them? You'd think that in their struggle for the good of humanity, they might have felt a bit of sympathy for the disadvantaged. Instead, they acted like the chosen people, more intelligent and more important than ordinary folk. In fact, they were preparing themselves for their future role in the government. Later on, when I became a member of the Polish youth organization in Poland, I met with the same disdain. There are some problems with the narrative. She records events very specifically at times, but then leaves out information (for example, who butchered the pig when it died?) In the epilogue, she does not mention what happened to people who figured so prominently in her life where they went, if and when and how she was ever able to meet them again. When did her parents die? Readers are interested in tying up the ends of a story. The title of the book reflects the sadness of a child whose life is turned upside down by events she does not understand. The madness off World War II and wars that currently displace millions of people are not rational. Flutsztejn-Gruda's account of the events that stole her childhood adds to the collection that should be preserved for history and taught to today's youth. Recommended. Harriet Zaidman is a teacher-librarian in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW

|TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- June 10, 2005.

AUTHORS

| TITLES | MEDIA REVIEWS

| PROFILES

| BACK ISSUES

| SEARCH | CMARCHIVE

| HOME |