| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XI Number 17 . . . . April 29, 2005

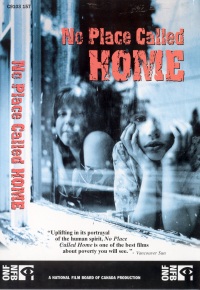

The Rices are nice, says Heidi, the French teacher at Our Lady of Grace School, near Barrie, Ontario. "The children are polite and beautifully brought up." All six children, from 14-year-old Richard to eight-year-old Zachy, hope to pursue professional careers. Their mother, Kay, and their father figure, Karl, are loving and devoted parents. Kay and her mother (the children's grandmother) are insightful and articulate. So why are they the subject of a movie? The Rices are poor. "It's what we are, not who we are," says 34-four year old Kay. They have recently moved to the small southern Ontario town of Angus, a community which the children like better than Barrie. One of the girls explains that, in Angus, people are all more or less in the same boat, and everyone goes to the second hand stores, but that in Barrie, a wealthier community, kids claimed that the Rices got their lunch from garbage cans and said they lived in a cardboard box and had baths out in the rain. Previous generations of the family have suffered in poverty. Kay's mother, who grew up in the pre-gentrified Cabbagetown section of Toronto, in a single parent household, left her abusive husband and moved to Barrie for a fresh start. Kay grew up poor there and was once beaten up by a schoolmate for the clothes she was wearing and had to be hospitalized. Cheerful and energetic, Kay works in restaurants and convenience stores, and Karl drives a taxi. Together, in 2002, they cleared less than $10,000, for the eight of them. They have always had a problem finding good housing -- hence, the title of the film, No Place Called Home. This title would seem to be an intentional twist on the old saying, "There's no place like home." True enough, but the adage implies that you have a home. No one wants to rent to someone with six children; consequently, they have lived in places with bad wiring and cockroaches. As the film begins, Kay and her family are in a house far too small. She and Karl are sleeping on the living room sofa and floor to allow the six children the two bedrooms. Kay makes a verbal agreement with her landlord to clean up another house that he owns in return for two months' rent. After a Herculean effort involving the entire family, the landlord reneges on his promise and demands $650 in rent, which Kay doesn't have. At this point, Karl loses his job. Film maker Craig Chivers explores the slippery slope of calamity that begins when one thing goes wrong for a poor family. Kay is forced to go to the St. Vincent de Paul, a Catholic charity, for food and clothing vouchers. There she meets the children's teacher, Heidi, who volunteers. When Heidi sees the family's living conditions, she can hardly believe that such nice children came from such an environment. "How can these children reach their potential?" she asks rhetorically. Film maker Craig Chivers seems to anticipate the viewer's questions. Why is Kay not on Mother's Allowance or some form of social benefits? The answer: she would have to give up most of her Family Allowance cheque and declare any earned income. The film follows the Rices' struggle with the landlord. Kay says that he has forbidden her to call in any inspectors to examine the state of the building. "Ditch the bitch" is his plan if she does. He drops off letters in the middle of the night, demanding his rent, and threatening to call the Children's Aid Society. This organization is a bogeyman to poor people who fear losing their children. Kay decides to take her case to the Ontario Rental Tribunal. "I'm a somebody," she says bravely, "and so are my children, and they are who I'm fighting for." Her high hopes, and those of the viewer, are almost immediately dashed. She cannot afford a lawyer, is turned down by legal aid, and must prepare her own case, assisted at the last minute by a paralegal who has never met them before the court date. The landlord files a countersuit for $10,000 in damages if the Rices will not drop their suit and move out of his house. Kay refuses to drop her suit. The tribunal orders them out of the house by July 1st, while taking the other matters under review. The judge presiding over the tribunal is unkind to Kay when she tries to introduce evidence of her work on the house. Going through her documentation, he says, will be a "one hedgerow at a time" process. Surely, reviewing the evidence is his job. Meanwhile, the Rices must find a new home. Kay phones over a hundred prospective landlords, but no one wants to rent to someone with six children. After holding a garage sale and trying to get a loan, the family ends up in tents in Kay's brother's back yard in Barrie. It is a wet summer, the tents leak, and Kay becomes ill. She is unable to attend the final tribunal meeting, leaving Karl struggling to present the family's case. September is approaching. If the Rices have no permanent address when school starts, will the C.A.S. break up the family? Then, Karl finds a well-maintained, freshly painted, carpeted house in Orillia. By admitting to only three children, and using Heidi's name as a reference, the Rices get the place. Kay muses as to whether it's worthwhile to teach her children to be truthful and to believe in justice. The tribunal found that the landlord owed them money but that they also owed him rent; they got $72 in the end. The film ends on a positive note. Shortly after settling in Orillia, Kay gets a permanent night shift job at the casino at $11.50 an hour. A year later, the family is still together in the pleasant rented house where the refrain is, "Shoes off!" Craig Chivers has challenged several myths about poor people, including the notion that they prefer social assistance to work. When Kay says that she hopes her children will "turn out to be good people" and "get what they want in life," most viewers will agree wholeheartedly. Highly Recommended. Ruth Latta of Ottawa, ON, is a teacher/writer/editor. Her mystery novel, Tea With Delilah, was published in November 2004 by Baico Publishing of Gatineau, PQ.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE - April 29, 2005. AUTHORS | TITLES | MEDIA REVIEWS | PROFILES | BACK ISSUES | SEARCH | CMARCHIVE | HOME |