| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume X Number 8. . . . December

12, 2003

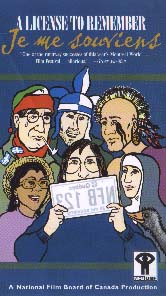

When director Thierry Le Brun set off across Quebec to find out the meaning of the phrase, "Je me souviens," he uncovers, in a freewheeling way, the complexity of Quebec. The phrase appears on Quebec license plates, and, as common a sight it may be on a daily basis, there is no consensus as to what is being remembered or who the "Je" may be. The motto was inscribed on the Quebec legislature by its architect, Eugene Tache, in 1880, and to this day, no one knows exactly what Tache meant. Some feel that perhaps he wanted to represent all the contributions to the founding of Quebec. Rene Levesque replaced "La Belle Province" on the license plates with Tache's phrase as a constant reminder to remember. He never did say what exactly they were supposed to remember. Early in the film, one can see that a simple question will not generate an easy answer. A cab driver, when asked the question, admits he was told what it meant but has forgotten. When he calls his dispatcher for guidance, he is told that he remembers his origins and ancestors. Thus begins a detailed and at times contradictory explanation. Le Brun first goes to Kahnawake and finds that the Mohawks there see the motto as French propaganda and a daily reminder that they have lost land, identity and culture. They remember that in the history books they are presented as the ones who massacred the French settlers. "Je me souviens" means that Quebec history began when Champlain came to Canada. To the 22nd Regiment, the famous "Van doos," the phrase calls to mind those who have died in battle. To others in the same regiment, it is a reminder of the battles fought in Quebec between England and France. To an English speaker, the phrase is a reminder that he, too, is Qu‚b‚cois as his family has been in Quebec for many generations. Quebec, he states, owes much to English Canada, and this should not be forgotten. At a commemoration ceremony for Jean-Olivier Chenier, a leader and martyr during the 1837 Rebellion, one man, overcome with emotion, wants everyone to remember how the rebels died at the hands of the English while trying to preserve their French heritage. Not so, says another participant at the same memorial. The 1837 Rebellion in Quebec, he claims, was the same as that in Ontario. The people were simply trying to fight corruption in government. Some remember that the Act of Union in 1837-8, the precursor to the British North American Act, was forced upon them. As a result, the French majority became a minority in the newly defined country. Some want to remember the power of the Roman Catholic Church and how that has finally been reduced. The liberation from Church authority was manifested by the sexual revolution. One speaker recalls when she moved into her English neighbourhood. A new neighbour asked her what it was that her people wanted. He told her that they "never used to have problems with our French Canadian servants." "That," she says, " is why the bombs." A Quebec man working in Manitoba is told by his boss to "speak White" when dealing with the customers. This phrase becomes the theme of some very powerful poetry. Another speaker, more pragmatic than nationalistic, sees the phrase as a piece of propaganda. He says, "They want us to remember what they want us to remember - that Indians are bad, the English are bad and that we won't be able to speak French unless we separate." He sees that as an "old wives' tale." While the past has value, he states that one cannot put it in the bank. A middle aged man is ashamed that his father, when speaking about French rights, speaks in English. The father is not a sovereignist. When the vote time comes, the speaker is hurt that his father's "no" vote will cancel out his "yes." An Afro-Canadian speaker remembers that at one time Quebec had 4,000 slaves. He states that, while things are not perfect today, times have been much worse. With these voices and many others, the film is a wonderful attempt to capture what it means to be Québécois. While LeBrun never gets a definitive answer to his question, he manages to weave the tapestry that makes up Quebec society and culture. All the speakers have opinions as to what is being remembered and who the "Je" is. While many of the voices disagree with each other, no one is wrong. The film has applicability in History, Politics, English (the use of point of view), Sociology and French at the senior level. The sound track contains some French rap performers so it will appeal to a youth audience. Highly Recommended. Frank Loreto is a teacher-librarian at St. Thomas Aquinas Secondary School in Brampton, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- December 12, 2003.

AUTHORS

| TITLES | MEDIA REVIEWS

| PROFILES

| BACK ISSUES

| SEARCH | CMARCHIVE

| HOME |