Books by Eva Wiseman.:

Eva Wismen photo by Barry Mallin.

Eva Wiseman

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

Eva Wiseman was born in Papa [it means Pope] in the Transdanubia region of Hungary close to the Austrian border. The events of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising led to Eva’s family’s fleeing first to Austria, where they lived in a refugee camp before ultimately immigrating to Canada. Four decades would elapse before Eva told the family’s story of escape and resettlement in her first novel for middle schoolers, A Place Not Home.

Eva Wiseman was born in Papa [it means Pope] in the Transdanubia region of Hungary close to the Austrian border. The events of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising led to Eva’s family’s fleeing first to Austria, where they lived in a refugee camp before ultimately immigrating to Canada. Four decades would elapse before Eva told the family’s story of escape and resettlement in her first novel for middle schoolers, A Place Not Home.

“I have a sister, Agi, who is two years younger than me. In A Place Not Home, which is very autobiographical, I used our middle names for the two girls in the Adler family. Ida is my sister’s middle name, and my middle name is Kornelia, and so that’s why the central character’s Nelly. When we came to Canada, we first went to Montreal. One person I didn’t put into the book was my great uncle who lived with us. He was a physician, and my dad’s a veterinarian. In Montreal, because they had to speak French and English, neither my uncle or father could get jobs.”

Eva acknowledges that “certain things I have fictionalized in A Place Not Home because it’s a novel.” One of the areas where fact and fiction diverge relates to Eva’s early schooling. With Eva’s father being unable to find employment in Canada, the family went to Israel. “I had started my grade 4 in Hungary, continued in Montreal, finished it in Israel, did all of grade 5 in Israel, started grade 6 in Israel, and then we came back to Canada. I didn’t put all that into the book as I didn’t feel another immigration added anything to the story and would just drag it out and not have much relevance.”

“My father loved Israel and got a job there right away as a veterinarian, but my mother didn’t like it. She felt it was unsafe and insisted that we come back to Canada. My mother, who never left her children and always listened to my father, came back to Canada three months ahead of the rest of us and found jobs for my father and my uncle. As in A Place Not Home, my father worked at night as a watchman to make money and to study English at the same time. My father’s not a man to whom languages come easily, but in 13 months of day and night studying, he learned English and passed the same exam as the Canadian veterinarians. I remember that he was in his mid-forties and his hair turned white during that year. He had a good career in Canada.”

Eva credits well-known Canadian author Tim Wynne-Jones with playing a critical role in her first becoming a published author. “I don’t think I would be published if it wasn’t for Tim.” Being new to the whole area of publishing, when it came time to send out the manuscript for A Place Not Home, Eva says she phoned the Canadian Children’s Book Center for advice. “They sent a list of publishers who accepted unsolicited manuscripts, and I went through it. To be honest, I even sent the manuscript to some of the publishers twice.”

While Eva’s manuscript was rejected many times, she says, “I had better rejections than anybody else. They would write me long pages saying, ‘This is what you should do. That is what you should change. And I would do it. Unfortunately, by the time I would do what they wanted, the person who sent these suggestions to me was no longer with that publishing company. However, when you’re a beginning author, if a publisher tells you to do something, you do it.”

One of the many people who received Eva’s manuscript was Tim Wynne Jones. “If I recall correctly, he was editing books for Red Deer Press at the time.” Although Eva’s book didn’t mesh with the type of books Red Deer Press was publishing, Tim thought its contents might interest Kathy Lowinger who was then with Lester Publishing. Eva remembers that “I was visiting my parents in Hawaii where they used to go after my dad retired. Kathy phoned me there and told me that she liked the book, and, that, if I wanted to, I could rewrite it, with no obligation on Lester’s part to accept it. It took me a year to rewrite the manuscript, and then Lester accepted it. The book was at the printers when Lester went under. Then Stoddart took over the book over, and then they went under. That’s why A Place Not Home is now at Fitzhenry & Whiteside. I used to joke that I was the kiss of death for publishers.”

“Kathy Lowinger has edited all of my books, and we work really well together. I really trust her. However, if we can’t agree where I really feel strong about something, Kathy will always say, ‘It’s your book Eva.’ For example, there’s a bullying scene in A Place Not Home where Nelly is surrounded by a group of boys who call her a DP (Displaced Person). Kathy felt the scene was a bit much, but I really thought it should stay in. She said, ‘It’s your book, Eva,’ and it stayed in. In that instance, I think my decision was the right one because kids always comment on it because name calling strikes a chord with them. What I like about kids is that they don’t pull any punches. If you don’t do something properly, the kids will tell you. If they like something, they’ll tell you too. I think kids are more sophisticated readers than we give them credit for.”

“In Puppet, however, I had a storyline where Morris is teaching Julie how to read. I really loved that storyline and their bonding over literacy. Kathy said that I was imposing twentieth sensibilities on these nineteenth century characters. I thought about it and realized, ‘Yes, she’s right. I don’t think that would have happened in that situation,’ and so I took it out, but with a stab in the heart to do it. I’m always worried when I edit something out. ‘Oh, boy, the book’s going to be too short.’ Then what happens is that you write something else in its place.”

“Looking back, I was always sort of oriented towards writing. I don’t know why. With my parents, there was always real pressure to do well in school. If I got 80 percent, my dad would say, ‘Why didn’t you get 90 percent’ My sister and I did really well in school since, for immigrant families, school is the key to your future success. Ironically, with my own children, when I used to tell them, ‘Why didn’t you do better?’ my parents would say, ‘Why are you so hard on them?’”

“I always wanted to be a writer, and I always wrote. As a child, I used to write in notebooks, and I used to make my parents listen to what I’d written. Initially I wrote in Hungarian, and when we went to Israel, I wrote in Hebrew, and then I came back to Canada where I wrote in English. Whatever country we were in, that was the language I always spoke to my sister. When my father moved in with me about six years ago, I found my old notebooks. It was strange because some of them were in Hungarian, some were in Hebrew, and some of them were in English.”

“In those days in the Fifties, we were the first wave of immigrants to Canada after those who had arrived immediately after World War II.. There were barely any government services for immigrants. It wasn’t easy. My sister and I were talking the other day and observed, ‘We had a tough life,’ but, you know, at the time, you don’t think that you have a tough life because we always had a very supportive family. My parents, especially my mother, always made us feel that we could do anything.”

“When I was a teenager, I worked at the Winnipeg Free Press where I used to write for the teenage page. I actually have my always supportive mother to thank for my getting the job. As I said, I came to Winnipeg in grade 6, and in grades 7 and 8, I went to Churchill High School where I won the yearbook contest both years. You had to write a little story, and my mother said, ‘This is so fantastic. You have to get it published.’”

“I remember taking the bus with my sister, who came along for moral support, down to the Free Press that was then still located on Carlton Street. I guess I was 13 or 14, and I said to the lady at the newspaper’s front desk, ‘I’d like to speak to the editor.’ I guess she thought, ‘What a joke,’ and so she called out ‘Mr. Sinclair! Mr. Booth!’ who were respectively the City Editor and the Managing Editor. I recall saying to them. “I think you should publish my stories in the paper.’ You know, not only did they publish them, but they also hired me to write a ‘teen tidings’ column on their teenage page. Each week, representatives from different schools would call me and I would make a little story out of the happenings in their schools. When the movie stars Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon came to town, I interviewed them. That column in the newspaper and a job as a copy girl during the summers at the Free Press paid for my university. I started the column about grade 8 or 9, and I did it until I graduated from high school. In university, I was the paper’s stringer on campus.”

“The only other job I had during my teen years was at the River Heights Public Library, and I lied about my age to get the job. I said that I was 15 when I was only 14 . They hired me as a page, but I got into trouble there because I used to ‘advise’ people on what books to read. They told me that I wasn’t to do that: ‘Only the librarians do that. You’re just to put the books back.’”

“Librarians had a big role in my life. When I was in Winnipeg’s Churchill High School, I had a wonderful librarian, Miss Neithercut. My English wasn’t that good because I got to Canada in grade six, and she noticed that I was trying to read the library’s books in alphabetical order by author, from A on,. I was planning to read all of the books in the whole library. She actually did what I think any superb librarian would do. She took me behind the counter and let me read easy books, Nancy Drew and adventure stories, but by the end of the year, I was into the senior high section. She then took me to Jane Austen, and she said, ‘You should try this.’ I didn’t know that it was a classic and that it was supposed to be hard. So I read all the classics. Miss Neithercut had a tremendous influence on my life. I think when you read good stuff, eventually you want to write even more. Sadly, now librarians have been eliminated in so many schools.”

“After high school. I was supposed to become a physician. My dad’s a veterinarian, and the reason he’s a veterinarian is that, when he was a student in Hungary, the government had the Numerus Clausus, something that actually appears in My Canary Yellow Star. What the term means is that, in each professional class, like doctors and lawyers, Jews were limited to a certain percentage. My father went into veterinarian medicine with the idea of transferring over into medicine, but he liked it and so he stayed there.”

“My father and mother survived the Holocaust, and then we immigrated. My father always wanted my sister and me to become physicians because he felt that you can always make a living if you’re a doctor. It’s a portable profession. So, as I said, I was supposed to become a doctor, but, of course, I was totally not suited to it, but, being a good child, a European-born daughter, raised by Europeans, I said ‘Fine.’ Then you rebel and don’t do what your parents want you to do. Years and years later, my mother said, ‘You know, with Eva, we made a mistake. Her talents were really not in medicine,’ but my sister had no chance. She’s a physician, a family practitioner.”

Eva’s rebellion didn’t fully manifest itself immediately though. “After high school, I went to the University of Manitoba where I did a science degree. I applied for Medicine, and I was actually accepted into the medical school. My dad went down to the medical school, and I don’t know how he did it, but he convinced them to give him a box of bones that they used for anatomy class. He brought it home and said to me, ‘We’ll review this summer.’”

However, the review never took place. “That was the summer that I got engaged. I was 20. In those days, you got married early. I wasn’t that interested in bones, and so there came my first real and only rebellion - Nathan and I eloped! I remember phoning home from Regina as Mrs. Wiseman, and my mother came on the phone and said, ‘How could you do this to me, etc, etc.’ When my father came on the phone, his only comment was, ‘Ok, you don’t have to go into medicine, but you’re going to go into education.’

“But then I didn’t go into education. I actually ended up getting a job at the Winnipeg Tribune because they paid more than the Free Press and we needed the money as my husband, Nathan, was studying. I worked there until I became pregnant, and then I stayed home and freelanced for the Trib Magazine and several other magazines. The day my daughter went to kindergarten I said, ‘I’ll go get a Master’s degree in English, and I’ll become a professor.’ That was the next goal. I went and did Victorian literature and just loved it. My thesis was a treatment of children in four Victorian novels. At the time, I was not thinking about writing books for children, but I think it was kind of useful for me later on. Anything you do in life is useful. Strangely, I’ve never taken a creative writing course.”

“Because I really liked English, even when I was taking my B.Sc., I used to get special permission to take English courses, and so I had my English prerequisites for an M.A. You could always take extra courses in your undergraduate degree. My taking these extra English courses should have made it obvious that this was the way I should go, but, in the meantime, there was the pull at home to go into medicine. My parents had a tough life, and they felt that you were safe if you have a medical degree. And there’s a point to their thinking. You can change countries, you can go through the Holocaust, everything, but if you have something like a medical degree, you can fall on your feet and make a good life again. So I can understand their way of thinking, but, as things happened, I got engaged, three weeks later I got accepted into medicine, and then we were married and off to Regina and Banff for a honeymoon. We ‘stole’ my in-laws car for the trip.”

Eventually, Eva did enter the Faculty of Education at the University of Manitoba. “What happened was that I turned 40. At the time, I thought that was so old. I don’t think that any more. I was home with the two kids, and I was driving them to things and taking courses, but I felt that there must be more to life than this. I had a sort of mid-life crisis, and I said to my husband, Nathan, ‘If I died, I‘ve had such a small life. I betcha that only a half a dozen people would come to my funeral because nobody really knows me. So, what should I do?’”

Eva’s father, of course, had the answer, the same one he’d had in 1967 when Eva and Nathan eloped. “‘You should go into Education.’ The idea kind of appealed to me, and I went into education and ended up teaching adult ESL. There was an Education professor who liked me, and while I was still taking his course, he asked me if I wanted to tutor some visiting Costa Rican professors in English. That experience led to my teaching adult ESL at an employment project for professional women, and I also taught the GED (General Education Development test). I just loved the job. The students were people who wanted to learn. Then came the stage where the federal government was cutting all the funding for these programs. While I actually got another offer to teach the GED, I thought, ‘This is the time I can try writing the book I wanted to write,’ the one that became A Place Not Home. The book was shortlisted for every major award and was on the New York Public Library’s Best Books for Teens list."

As Eva has already noted, she has never taken a formal writing course, but her daughter and a true book person in a local book store, McNally Robinson Books, played a role in Eva’s learning the craft of writing for juveniles. “My daughter was just reading the ‘Baby-sitters Club’ series. I was very upset about that, and so I took her to the book store to find some better books that she would enjoy, and I started reading what she was reading. One of the staff members in the children’s department, Felicité Warner, would see me and say, ‘Oh, Eva, you have to read this. You have to read that.’ I read a fantastic number of children’s books, but, in my reading of these books, I didn’t just read for pleasure. I would also try to read in an analytical way to see what these authors, for example, did to create tone or how they took a character from one scene to another scene."

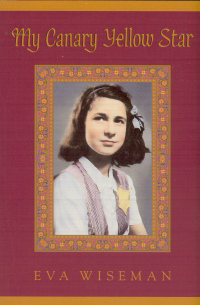

Five years were to pass after was published and Eva’s next book, My Canary Yellow Star, appeared. This work of historical fiction, which is told from the perspective of 15-year-old Marta Weisz, deals with the period in Hungary between March 19, 1944, the day German troops entered Budapest, Hungary, and January 17, 1945, the day when Soviet troops liberated Pest. The lengthy interval between books was not because Eva was without ideas, but it was during this period that Eva’s mother became ill and died.

About My Canary Yellow Star, Eva says, “That one has the least of my family or us in it. I remember that when I was growing up, I heard about Raoul Wallenberg, and I noticed that, in my family, it was always just the four of us and one great-uncle who had survived the Holocaust. My sister and I were born after the war. I never knew my grandparents, but I was aware that my friends from Budapest, Hungarian Jews, had big extended families. That was when I first heard about Wallenberg. I thought it was an interesting story, and that is why I wrote the book.”

“To write My Canary Yellow Star, I interviewed a lot of people who were saved by Wallenberg. My character Marta is not based on one person. In writing, you compile your character, and you take a little bit from here and there, and so Marta is a compilation of many people. However, many of the incidents in the book are based on actual happenings. For instance, there’s that incident in the book where they find a bunch of little kids lying on school desks because there were no beds. That happened.” My Canary Yellow Star won the McNally Robinson Book for Young People Award and was also on the New York Public Library’s Best Books for Teens list.

“I love doing the research for my books. In fact, I like it as much as the writing. For A Place Not Home, the only research I had to do was to talk to my own parents and pull things from my own memory of when I was nine. For My Canary Yellow Star, I went to Budapest. If you walk on the streets that Wallenberg walked, go into the buildings into which he was said to have gone, you can almost touch it and taste it. I believe my having that experience makes the book’s contents much more realistic. I think it’s really important for a book to have the proper setting or flavour, a sense of the times, and it goes beyond just how people dress and talk. There’s a ‘feel’ to it. I think if you do good writing, and, if you have the proper knowledge and maybe a firsthand look, then you can get that into your books.”

Winner of the Manitoba Young Readers’ Choice Award, No One Must Know, Eva’s next book, is set in 1960 in an unnamed city (Winnipeg) and has Toronto-born Alexandra, aka Alex, Gal, almost 14, as its narrator. Initially, the book does not seem to have any connection to the Holocaust as Alex appears to be a Catholic, but Alex’s parents have been hiding a secret from her. Determined that “no child of [ours] would suffer like we suffered,” Alex’s parents, survivors of Auschwitz concentration camp, have changed their surname from Goldberg to the more Hungarian-sounding Gal and are passing themselves off as Christians.

“With No One Must Know, I did a little research into what Winnipeg was like in 1960. Because I lived in Winnipeg at that time, I do remember what it was like, but I wanted to get the tone, the atmosphere. To me, that’s most important. I also talked to seven or eight people about their experiences in ‘passing’ as Christians, and that’s why I didn’t specifically identify the setting as being Winnipeg (though Winnipeggers will likely recognize their city). I didn’t want people saying about the book’s characters, ‘Oh, that character must be him or must be her.’”

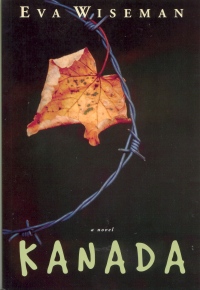

Short-listed for a Governor-General’s Literary Award, and the winner of the Geoffrey Bilson Award for Historical Fiction, Kanada is actually a prequel to No One Must Know, and its contents are based on Eva’s parents’ experiences during World War II when they were incarcerated in Auschwitz. “I know it’s a very ambitious thing to say, but I consciously set out to write a story of the Hungarian Jews throughout the Holocaust. Most of the Holocaust books for kids are about the Polish Jews, and there’s a very good reason for that. The Polish Jews were deported much earlier than the Hungarian Jews who were taken away in 1944 when Germany was already losing the war, and they knew they were losing the war. Consequently, not much has been written for young people about the Hungarian Jews, but I think that, if you suffered even one minute, it’s a minute too long, and my whole family got wiped out.” As to the book’s award recognition, Eva remarks, “You can’t think of the awards because it’s crippling. I’m not saying that I don’t want to get awards. I’m thrilled. I have writers’ insecurities, and recognition says, ‘You’re OK,’ but I think the work, itself, has to be what is motivating you.”

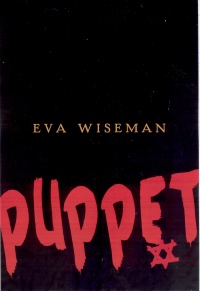

In Puppet, Wiseman’s most recent novel, she again returns to the persecution of Hungarian Jews, but this time she places her novel in a much earlier time period, 1876-1883, with most of the action occurring in 1882-83. Puppet’s origins are actually in Eva’s childhood. “When I was growing up, whenever I tattled on my sister, my mother would say, ‘Don’t be a Morris Sharf.’ When I asked her who he was, she said, ‘He was a traitor to his family,’ All the Hungarian Jews know about him and what he did.”

“I was looking for a topic for another book, and the Holocaust is very, very important to me. I wrote about the post-Holocaust period in No One Must Know which again dealt with the effect of the Holocaust on the second generation, I wrote about how the Jews were saved in Budapest in My Canary Yellow Star, and in Kanada about what happened in the countryside, my family included. I felt I’d sort of ‘done’ that, and you don’t want to repeat yourself though I do have in the back of my mind one more Holocaust book which is very different, but I don’t know if I’ll ever write it.”

“Anyway, I read about Morris Sharf, and I found out what happened in Tisza-Eszlar, a small Hungarian village, in 1882-1883 regarding a blood libel case. I can’t swear to it, but I don’t think this event has ever been done for kids. It’s not exactly a cheerful topic.” In Eva’s book, the precipitating action is the disappearance of a young Christian girl, Esther Solymosi, on Saturday, April 1, 1882. Esther’s going missing becomes associated with a “Christian belief” voiced by one of the town’s busybodies: “You know what the Jews do. Every year, before their Easter, they kill a Christian child and use his blood to make their matzo.” With Esther’s continuing absence, rumors lead to a government investigation, and four Jewish men are arrested. Despite the fact that there is no body, they are ultimately charged with killing Esther, their supposed motive for her murder being Jews’ need of Christian blood at Passover. Accused of complicity in the murder is Joseph Scharf, the synagogue’s beadle or caretaker, and it is his teen son, Morris, who, under intense psychological and physical pressure by the conviction-focused prosecution, finally submits and becomes the chief accuser, his strings being pulled by the prosecutors. Puppet’s narrator is Julie Vamosi, a young girl whose role as a servant, allows her to unobtrusively observe the goings-on.” Puppet was chosen as “A Top 10 Historical Fiction for Youth:2009" by Booklist.

“Puppet was difficult to research. First of all, I had friends who went to Hungary, and they brought back several volumes written by the chief defence lawyer which were written in Old Hungarian. Hungarian is a phonetic language, but it’s very different to read it than it is to speak it, and I just couldn’t hack it. Remember that I was starting grade four when we left Hungary, and, while I’m fluent in an informal Hungarian, my Hungarian is like a 10-year-old would speak. I kept falling asleep over these books, and I just couldn’t read them. I found some scholarly articles in English to get the facts of the case, and I also did some Internet research.”.

“I really simplified the case because there were hundreds of people who were called to testify. For example, the rafters on the river who found Esther’s body got implicated. The case was so convoluted that I had trouble understanding it myself, and so I would say to myself, ‘What do I want to do here?’ And what I wanted to do was to focus on the boy, Morris. Nobody had really ever focused on him, but he was the lynchpin of the whole case, and so that’s what I did. As far as Julie, the book’s narrator, is concerned, she’s a compilation of two characters. She’s fictional in terms of the relationship between herself and Morris, but there were two young maidservants who were kind of involved in the case.”

“I had to read through so much, and I did read the actual transcript of the trial in Hungarian. Reading that went a little bit easier because it was in a question and answer format that had been printed in a contemporary newspaper, the one that I give credit to at the beginning of the book. The scar on Esther’s right foot is absolutely real. There were several autopsies of Esther’s body , but I give the scar more importance than it had in the actual trial. The prosecution was totally corrupt, but this was a trial witnessed by many people, and Morris’s testimony just fell apart. What’s interesting is that Morris reconciled with his parents, became a diamond cutter in Vienna, I believe, and supported his parents in their old age. As soon as the Jews were declared not guilty, all over Hungary there were protests and pogroms against the Jews.”

Reflecting on her writing, Eva says, “I think you have to write about what you’re passionate about. These are the topics that interest me. I wish I could write something like Harry Potter and then retire to who knows where, but these are the topics that really interest me. Most authors say, ‘I have a character, and I work out of the character.’ I don’t. I have an historical event.. I’m very interested in how events outside our own control impact our lives, and how it affects the character For example, if it wasn’t for the Hungarian Revolution, I wouldn’t be here in Canada. The Holocaust changed my parents’ lives forever. We think we’re in control of our lives, but there are always greater forces outside.”

“You’re sort of creating a world when you write, and because you write for kids, you’re changing the world because you’re influencing the future generation. Even at my age, I’m idealistic, but the whole process and act of writing, I just really like it. Don’t think that it’s not work because it’s work for me.”

As to how she utilizes her time, Eva explains, “It’s hard. I’m supposed to be having regular office hours. The idea is to be writing all morning, then take a little break and write in the afternoon until about three o’clock. Very often what happens is that some ‘emergency’ comes up, and then the writing doesn’t start until the afternoon. Then I’ll go until 8 or 9 o’clock at night. If I have a contract, I’ll write every day. I’m pretty good then because I know it has been done, and I’ll write every spare minute I have.”

“I do a ‘billion’ drafts. I do the first draft by hand at the kitchen table, and then I go into my office. I enter what I’ve written into the computer. Then I print out a hard copy, and I change the hard copy by hand.. I reenter it again. I don’t actually do any writing on the computer. I think if you have a pen in the hand and the paper, something happens. You think better. I always say I’m a slow thinker. I don’t have a certain number of pages which I produce each day. I just go at it, and I write all the way through. Well, what I do is that I write a chapter, then I’ll print it out make changes for one draft, and I will probably reenter it right away so that I’ll be at the second draft, and then write again, but every time I read it, something ‘gets wrong’. Even when I’m doing a reading of one of my books, I say to myself, ‘Oh, how could I have done this? This is terrible. What’s wrong with my editor? How could they allow this to pass?’ I actually change stuff when I read. You do your best, but you’re never really satisfied. To be honest, I’ve never reread any of my books. Maybe I should, but the truth of the matter is that, by the time you finish, you don’t want to see it again.”

Looking ahead, Eva says, “I just finished an essay for a Penguin anthology called Piece by Piece, edited by Teresa Toten. They asked writers who were not born in Canada to write about how they became Canadians, that is their memories of their first stirrings of becoming Canadians.”

Eva also has a two book contract with Tundra and is presently doing the research for the first one. “It’s planned to come out in 2010, and. again, it will be a Jewish story because that’s what I’m passionate about. It’s going to be an exciting adventure story that takes place in the fifteenth century with a female central character, but the book also has a very strong male character. The one after that, which I hope will come out in 2011, I’m not going to say much about other than that it will be a departure for me. It has a male and a female character, and it’s going to take place in the 1990s. It’s going to be quite different although, again, it will have a Jewish theme.”

This article is based on an interview conducted in Winnipeg, MB, March 19, 2009.