Karen Krossing

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

Karen Krossing's childhood was rich with family stories told by her mother. One such story tells how determined Karen was to follow her own path, even before she was born. For some reason, she waited an extra two months in the womb before consenting to be born. Then she stubbornly sucked her thumb, rather than bother with breathing. Karen was born November 28, 1965, in Richmond Hill, ON, but grew up in the neighbouring community of Thornhill, a suburb just north of Toronto.

Reflecting on her childhood career aspirations, Karen says, "I don't remember wanting to be a writer as a young child, but I sure wanted to by the time I was in high school." Yet conversations with her mother have led Karen to consider that perhaps her desire to be a writer might have actually begun much earlier. "My parents were both teachers, and Bryan Buchan, one of the teachers at my mother's school, wrote a book in 1975 called The Dragon Children. It was illustrated by Kathryn Cole who, much later, edited my book Take the Stairs. I was 10 when Bryan's book appeared, and my copy is inscribed, 'To Karen, one of the greatest writers I know, Bryan Buchan.'"

"That inscription in Bryan's book prompted a discussion with my mother. I grew up in a family of avid readers, but I didn't read as much as my older sister did. She would read when I wanted to play with her, and I would get annoyed. I read less because I was writing instead. Evidently, my mother would take my writings to school and give them to Bryan, who would comment on them. My mother said I wanted to be a writer back then, and that I was busy writing at that early age." While neither Karen nor her mother kept any of Karen's childhood writings, she does have a comic book that she wrote and illustrated at age eight. "It was called 'Lucky Lisa' and involved a mother, father, Lisa and her dog Max. I illustrated it with simple drawings that clearly show why I'm not an illustrator today."

"Another of my mother's family stories is that, even before I began writing, I would play contentedly with anything, even a set of spoons. They would be my characters, and I would talk or sing their parts, making stories as I played. My mother is a natural storyteller, and I grew up with constant stories. Because stories were important to me, I made stories too."

"When I got to high school, I wrote mostly short pieces and poetry full of angst. As I said, my goal then was to become a writer. However, near the end of grade 11, I came home one day and announced to my mother, 'I'm sick of high school. I hate it. I'm going to go to summer school to take my grade 12 math so I can graduate next year.' And that's what I did, because we didn't need to have a certain number of credits to graduate, just our grade 13 credits. I took grade 12 math in summer school, and then, because math is easy for me, I took three math courses that next year. I would have graduated in June, but I got early acceptance to the University of Guelph, so I went there. My high school still thinks of me as a dropout. I was only 17 when I left for university, and I grew up fast in my first year."

"I took English at university. I planned to study what I enjoyed then and later take a program that would get me a job. I liked reading, and, at that point, there weren't many writing programs. I published some of my angst-ridden poems at Guelph in a little magazine called Spilt Milk. I really liked Guelph and wanted to live there after graduation, but there were no jobs for me then."

"My first job after graduating with my B.A. in 1986 was at a typesetting company in Toronto, where I proofread things like Camera Canada and the Holstein Journal. I'd never read an advertisement for cattle sperm before; it was an eye-opener. I also proofread cheques: the addresses and the bank account numbers on hundreds and hundreds of cheques a day. It was so monotonous."

"I stayed at that company for about a year, then I got a job at an educational publishing company called Houghton Mifflin. I was there for over two years, starting as an Editorial Assistant in the math division. Later, I switched to become Editor in language arts, which was more to my liking. The language arts program was based on 'original' literature, so we were reading children's literature and commissioning original writing, which was great fun. One day, the company sent me to CANSCAIP's 'Packaging Your Imagination,' which is a day of workshops for those interested in writing, illustrating or performing for young people. I remember being amazed and thrilled that day to find so many interesting creative people who were supportive of new writers. I wasn't writing much then. I guess I'd found my way into the world of writing before I was ready."

"After Houghton Mifflin, I went to Oxford University Press where I worked for two years as an editor of language arts and social studies textbooks. I discovered that I liked working with authors. A good editor is a writing coach, and I learned a lot about writing from that time. First of all, being a terrible speller, I learned how to spell better, and I learned advanced grammar and word usage. I also learned how to help somebody else write the book he/she wants to write. I enjoyed the dynamics of working with an author in that way. With educational publishing, some textbooks are partially ghost-written by the editors, and I liked that aspect too."

"My third publishing job was with McGraw-Hill Ryerson, and I stayed there for six years. They were located in Whitby, about forty-five minutes from Toronto, and I drove out every day to work on social studies, language, business and law textbooks. Again, I did some of the writing, like when I interviewed a feng shui master and then wrote a profile for a retail-marketing book. It was great to be involved in the planning of a book and then nurture the writing process along the way."

"I was 20 when I met my husband-to-be, Kevin. He was just 18. I was finishing university, and he had finished high school. When I met him, he was working at Canadian Tire, but he went back to school after that, and he now runs his own consulting business. We've been together ever since we met, and we married in 1992. Paige, our first daughter, was born two years later; then, Tess, our second daughter, was born two years after that. I worked at McGraw-Hill until Tess was born, but I'd been taking a technical writing program at Glendon College at night. My plan was to freelance as an editor and technical writer after she was born, and I did for a while."

"Kevin and I both agreed that we wanted to raise our children ourselves, not have them in daycare for most of their waking hours. We planned that we would both work only four days a week and share the parenting. It didn't work well because most jobs demand more than part-time hours. Eventually, Kevin was working five days a week, and I worked only three while the kids were with a babysitter. But my corporate clients required more commitment than that. My pager would go off just as one kid was having a temper tantrum or suffering a grievous injury. I didn't want to put the kids second, but my clients wanted instant results. I decided that I would use my work time for creative writing. It was less demanding and could wait if the kids needed me. Creative writing fit with our parenting plans, but it also fit with my personal goals."

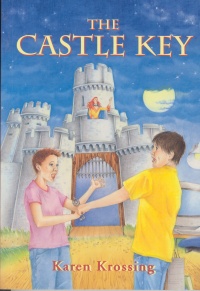

"My goal was still to be a writer at this point, but I had assumed that I would start writing fiction when I retired. Now, I had this fabulous opportunity. I made a plan. I would try writing fiction for five years. If I had no positive results in that time, then I would stop writing full-time. Five years later, I had a short story and The Castle Key published, plus I had a grant for my next project. I said to Kevin, 'Well, it's been five years. I guess we should talk.' I asked his opinion about continuing to write because a writer needs family support. It's not an easy job, or a well-paid one. But Kevin just laughed and said, 'There's no reason to talk. Keep writing.' He's always been very supportive."

"I didn't know I wanted to be a writer for children. When I was writing at home those three days a week, the first thing I wrote was a children's novel called 'The Dance Without End.' I didn't practice even a short story first. Since then, I've thought a lot about why I write for children and teens. I suppose I like the stages of children, and I especially like the teenage years. I find them fascinating. I also like imaginative literature and speculative fiction because there so much room and scope. Children and teens seemed a natural audience for me."

"'The Dance Without End' is unpublished and should remain that way. I wrote it very quickly, in about six months, and then I wrote the first draft of The Castle Key. I sent the two manuscripts out to an editor friend and asked her to read them as a favour. She gave me great feedback, but she also clearly stated that they were far from being publishable. It was a shock. I hadn't realized how many drafts I would have to write. When I was editing nonfiction books, I'd learned how to write, but I didn't know much about character. Since the basis of fiction is character, I was in trouble."

"The 'Dance' novel had too many problems to try to fix, and I didn't really care enough about the book to attempt to revise it. I don't regret writing it, because it taught me so much about what not to do. Over the next three years, I reworked The Castle Key. I went back to the beginning to learn about character development. That was my biggest challenge: how to show character through action, dialogue and description. The nonfiction that I'd been writing had been so different. I hadn't worried about point of view or character. That was my learning curve."

"I had researched The Castle Key thoroughly. At least I knew how to research from my years as an editor. I had learned about castles, determined the exact time period for my castle, and made maps and floor plans. What changed in the new drafts was characterization. When I revised The Castle Key, the characters began to talk to me and tell me what they wanted to do, rather than me determining the plot. It was a huge shift. Some of the characters developed new names. Eventually, I found Moon's voice, and let her tell the story."

"I think that all fiction is a blend of reality and imagination, and any book reflects the writer and the writer's world. Take the Stairs is based more closely on my world, but parts of the The Castle Key are based on me too. Moon, in particular, is similar to me. Moon starts off with a wish to have her mother back, and she believes that she can get that through magic. I wished that I could be a writer, so I played at it, pretending I was a writer for three days a week. I didn't tell anyone, other than Kevin, what a ridiculous task I had chosen. My friends and family all thought I was still doing 'real' work. So I wished I was a writer, and Moon wished that she could get her mother back, and we both went on the journey together. Like Moon, I believe that a little magic helped me along the way."

"I have a file full of rejection letters for 'The Dance Without End' and for The Castle Key. I don't know why I keep them. Rejection is never easy, but it's a part of the writing life that I've had to accept. An important quality for a writer is to be determined enough to continue writing, no matter what happens. This attitude paid off eventually when Napoleon agreed to publish The Castle Key, after another major rewrite."

Karen's first published piece was actually a short story, "Dragon's Breath," which she had entered in the Thistledown Press Short Story contest and which appeared in 1998 in Opening Tricks. "I was thrilled when I learned my story was going to be included. Peter Carver was the collection's editor, and, when we were discussing the editing of the story, he told me about a writing class that he taught through George Brown College and suggested I take it. I signed up for his fall class in 1998, and I've been taking it on and off ever since. He teaches an introductory class and then an advanced class where people read works-in-progress. Some writers have been attending his advanced class for 10 years or more. It's addictive and full of fabulous writers and critiquers. I was in Kathy Stinson's writing groups sometimes too, which were originally an offshoot of Peter's class. Both Peter and Kathy attract a dynamic group of writers who they nurture and encourage. I'm lucky to be part of that."

"I stayed so long in Peter's class because I wanted to be a better judge of my own writing, which is so hard to do. If I read a piece just after I've written it, I think it's pretty good. I can see how far I've come, but not how much further I have to go. So I've learned to put a piece away and read it again when I don't have an emotional attachment to it anymore. That may be a day, three weeks, or, with a novel, six months later. It takes time until I can judge my writing more clearly. I've developed better critiquing skills and learned how to respond to others in constructive, supportive ways. I've been involved with different writing groups through the years, and sometimes I trade manuscripts with other writers and exchange feedback. At times, I read a chapter to my daughters and my husband, but I learned long ago that other writers are the best critiquers."

"I started writing the first of the stories for what became Take the Stairs in 1998. I had written one of them before I started Peter's class. They weren't a collection to begin with; they were individual stories. Because I had written two novels, I wanted to experiment with shorter fiction, using different characters and different writing styles. I wanted to try writing in third person and first person, using male and female characters, with angry and placid protagonists. I just wanted to play. All the stories in Take the Stairs except 'Jennifer's Story' were workshopped in Peter's class, which made them stronger. The stories weren't linked to begin with. They were separate, and I sent them out that way in my search for a publisher."

"Second Story liked them but never responded with an absolute yes because the stories weren't 'ready.' This is part of my struggle to learn when a story is 'done' and to be a better critiquer of my own work. I sent the collection out before it was ready, and it sat at Second Story for two years before it was accepted. After about a year into the two years, I talked to Margie Wolfe, the publisher, about publication and she said, 'I'm not sure. I'm thinking about it still.' I decided to revise the collection. I looked at my original notes and found an idea suggesting that 'Hide and Seek' become the first story in the collection, introducing all the characters who live in a rundown inner city apartment building. Each story would then be from the point of view of a different character from that building. I read that note and thought, 'Why didn't I do that?'"

"So I got rid of a number of the original stories, wrote new ones, and linked them. The characters names often changed. The first story I had written became the first story in the book, 'Hide and Seek.' The idea of the building as a character was there from the beginning, and I started the book with a short, piece about that 'character.' 64 Wilnut Street, aka The Building, comes from my husband Kevin, who grew up in some unpleasant apartment buildings in the Toronto area. When we first met, I was at his family's apartment often, and that building, as well as others he lived in, are a basis for The Building. The last story, which is also the title story, 'Take the Stairs (Tony, Apt. 818)' is very much Kevin. He's the guy who didn't want to admit where he lived."

The 13 stories in Take the Stairs have an almost equal balance of male and female characters and are largely told in an alternating gender format. Karen determined the order of the stories. "I wanted to make sure that there was a balance of male and female characters in the book. Most of the new ones that I wrote when I went back and reworked the original stories were male stories like 'Opportunity (Flynn, Apt. 606),' 'Easy Target (Asim, Apt. 1005),' 'Off the Couch (Roger, Apt. 615)' and 'Take the Stairs (Tony, Apt. 818).' I killed off some female and some male stories that weren't strong enough. Asim existed in a different form. The only girl that was new was Jennifer. All the rest were original girls. I did choose the alternating male/female format, probably because of my overly organized mind. The stories are also somewhat chronological, although some stories, like 'Grains of Sand (Magda, Apt. 220),' stretch over a longer period of time, and some of them happen within a few days. The collection also has the structure of Petra's disappearance, which begins in the first story and ends in the last."

"I knew I needed a story for Jennifer, and I couldn't get it. She existed in 'Hide and Seek,' the original story, and I never knew why she was so flirtatious. I had the beginning scene of Jennifer's story, but I didn't know where it went next, and I didn't know what to do with it. As I was reworking the collection, I saw Margie Wolfe at an event, and I told her how I had been reworking the manuscript. She said, 'That sounds interesting. Send it to me,' and I did. Jennifer's story wasn't in the collection when Margie accepted it. Margie did say, 'I'd like to see a gay or lesbian character in there.' At that moment, Margie confirmed for me that I'd found the right publisher for the book. I thought about what she said. 'Was I going to write something new?' I thought about Jennifer's story that was partly written and realized, 'That's why she's behaving that way,' and then the story came out quickly."

To the observation that the female adolescents in Take the Stairs largely face tougher problems than do their male counterparts, Karen responds, "I noticed that too, and that concerned me when I was working on the stories. These girls' problems seem so big. But these stories are based on my life, people that I know and people that I grew up with as a teen. There are many tougher things, in some ways, that some girls have to face. One reason I like Jennifer is because she's so strong. These characters really live for me, and some stories threatened to become novels. 'Night Watch (Allie, Apt. 412),' which is about a girl on suicide watch for her depressed mother, is one that pushed to be more than a short story. I really like writing for teens. It's such an interesting time, and short stories for teens are so wonderful because there are so many 'dramatic' moments that are life changing."

The collection also contains a mixture of races, but the characters' racial origins are understated. "I did that on purpose. I didn't want to say 'the black guy' or 'the Asian girl,' and that's partly because I don't think that way. Toronto's a very multicultural society, and there's a fantastic blend. For example, my kids grow up with different cultures within their own classrooms. To them, it's just, 'My friend, Maria.' It's not 'the girl that's half Filipino and half Scottish-Canadian.'"

Another part of Karen's life is doing writing workshops for adults and children. She explains, "It's a natural evolution of being a writing coach, which is the way I thought of editing. When I tell people that I'm a writer they often say 'I want to write a story too,' or 'I have a half-finished novel.' I hear it all the time. My sister, who studied as a chartered accountant, once said to me that she didn't feel like she had the right to write, which is what I thought when I was beginning too. I replied, 'Well, you can do needlepoint, and you don't feel like you need to get permission before you begin.' Now, she writes, when she has time."

"I feel that it's important to nurture writing wherever people feel a need to write, and it's not always necessarily writing to become a published author. I have stories that I've written for my kids based on things that we've said or done, and we self-publish them. One, with a print run of two, is called 'The Spilling Fairy.' It's based on the fact that I spill and break things often. Once, when I spilt grandly, I made up this story as an excuse for why I spill. I wrote it down, and one of my daughters illustrated it. Stories like that have as much value as published ones. Some of the people that I teach or coach may not become world famous writers, but they have important stories that they need to share with whomever is going to be their audience."

Karen's first "teaching" experience was with a private writing group that sprang from Peter's class. "I proposed that we go away for a weekend, and I structured the weekend with writing exercises and discussions, using masks to develop characters and other fun activities. I'm a big believer in writing exercises as a springboard to creativity. Then I got an email about three years ago from the Learning Annex, an alternative adult-education organization that offers short, inexpensive courses and seminars on personal growth, asking if I would do a writing workshop for them, and now I do that on a continual basis. The audience is made up of real beginners, people who want to write. Some of them have started, and some of them are just thinking about it. There are so many voices that want to be heard, people who want to write. I also do writing workshops with kids in schools. In 2003, I taught a workshop on writing fantasy and science fiction for the Canadian Children's Book Camp. We were creating new worlds, drawing maps, and determining characters to start stories with fantastical worlds."

After a time-slip fantasy and a YA collection of realistic stories, Karen says that her next book is set in a future world. Titled 'Pure,' it's for a teen audience and will be published in 2005 with Second Story. "The main character, a 15-year-old girl named Lenni, lives in a society where genetic enhancement is forbidden. She discovers the horrifying truth: that her parents illegally enhanced her, in fact, choosing who she would be. Lenni has to deal with the prejudices against her and escape from the Genetic Purity Council, or Purity. The book is about finding out who you are and about how we create ourselves. Lenni is an artist so she's involved in the act of creation, but the book also deals with how we create ourselves through genetics and how we will treat our genetic underclass."

"The idea for 'Pure' came when I heard an interview with Maureen McTeer on CBC radio. She had published a new book about the ethical and legal implications of genetic technologies. The interviewer asked something like, 'How would a teen feel to have been genetically 'arranged' by his/her parents?' With that one question, I thought 'Wow!' I knew this was an ideal topic for a teen novel. It's perfect because teens are determining their futures, breaking away from their parents to define themselves, and to find out that your parents had decided your genetic makeup would be so invasive."

"What I've learned to do with any idea, including 'Pure,' is to stop, think about it, and see if it has enough staying power for me to work on it for years. I'm a ponderous thinker, and some ideas feel really good at the beginning, but I've learned to wait and think then decide which ideas I'm going to develop."

"I work on more than one project at a time, and they are all at different stages. Right now, I'm concentrating on 'Pure' steadily, but I have two other books started in first draft. I've stopped them for now because I have to ponder 'Pure.' In the meantime, my subconscious is hard at work on the other books, and I jot down ideas for them as they come. Characters come to me slowly, intuitively. So right now, I have three projects on the go, but I'm not writing on them all the time, and I can take time to think."

"All of these stories start with a flash of an idea or character or 'something.' For instance, the story 'Hide and Seek' started when I was going on a short tour of someone's home, which was as big as a castle, near Casa Loma in Toronto. The house belonged to a client of Kevin's, and several young employees on the tour with me giggled and said, 'Wouldn't this be a great place for hide and seek?' I thought about a story where kids were playing hide and seek, but the game meant more to one character because she had more reason to hide. Boom! The idea came, and then I worked with it over time."

Asked if working on three books at once is confusing, Karen clarifies how she deals with more than one book at a time. "It takes me a long time to get up and started on a project. When I return to 'Pure,' after working on a different book, I have to get into character before I begin. Right now, Lenni, is 'living' in my head so I'm madly writing that book. I want to keep Lenni in my thoughts and write as far as I can. When I come to a natural stopping point, because I don't know what happens next or because I'm not sure how to deal with a problem in the manuscript, I switch projects and let my subconscious work out the kinks. Then, the gear-up process for the next project is again huge, onerous, and terribly difficult."

"To get started writing each morning, I'll read over yesterday's work and revise as needed. Then I'll write the next scene, and so on, until I get a whole draft. Sometimes, I'll write chapters out of order, or three at once, to see how the story works as a unit. With my latest book, 'Pure,' I'm on my ninth draft, and I've kept a copy of each version. With the first two novels I wrote, I didn't keep copies of distinct drafts. 'The Dance Without End' and The Castle Key were written from chapter synopses. With 'Dance,' I worked with the plan too strictly whereas with The Castle Key I let the plan flow. And with Take the Stairs I wrote notes before I started each story, character and relationships notes, any research I needed, such as how chicken eggs hatch for "Off the Couch (Roger, Apt. 615)," and then I wrote the story to discover what would happen. I let the character drive the story."

"I write almost every day. If I don't write, I get grumpy. I write in my home office on a computer. I'm very strict about writing. I sit down and write the whole time, and I don't allow myself to do anything else, like run errands or visit friends. This is writing time; that's what it is used for. My writing days are not regular because of my kids. Sometimes my kids, who are now both in school, will come home for lunch, so I have to stop writing. Then, I get about three writing hours in the morning and about two in the afternoon. It can be hard to get started again after lunch. When they're not home for lunch, I write from 9 until 3, only stopping when I'm hungry. If one of the kids gets sick, then I feel frustrated. I'm glad I can be there for them, but I also think, 'It's not fair. I was planning to write.' Yet I decided long ago that people would always come before writing. People are more important than books, even though books are really, really, really important."

Books by Karen Krossing

Photo credit: Jackie Scott.

This article is based on an interview conducted in Toronto, ON, on February 28, 2004.