Michelle Gilders

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

Books by Michelle Gilders. This article is based on an interview conducted in Winnipeg on December 11, 2002 Visit Michelle's home page at http://www.michellegilders.com

Born on Christmas Day in 1966 in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, in England, author, photographer and biologist Michelle Gilders describes her birth place as "a very attractive little market town that's surrounded by farm land. Quite an old town with lots of old churches, pubs and town buildings, it's about 50 km north of London. One of Hitchen's claims to fame is that there's a pub in Hitchen at which Queen Elizabeth I used to stay on her way through."

Born on Christmas Day in 1966 in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, in England, author, photographer and biologist Michelle Gilders describes her birth place as "a very attractive little market town that's surrounded by farm land. Quite an old town with lots of old churches, pubs and town buildings, it's about 50 km north of London. One of Hitchen's claims to fame is that there's a pub in Hitchen at which Queen Elizabeth I used to stay on her way through."

As a child, Michelle had a rather unusual life goal. "I wanted my own zoo. I wanted to be Gerald Durrell or David Attenborough. I dragged my parents and older brother around to every Royal Society for the Protection of Birds' sanctuary or Water-fowl Trust and zoo in the United Kingdom. I always had a fascination with wildlife and wanted to do whatever I could to get close to wildlife. On weekend excursions and summer holidays, my mother and father would always take me out to museums and zoos. I loved to read at a very young age, and I just devoured any books they would give me. I was probably about seven or eight years old when I was reading Gerald Durrell's books about his adventures in the world catching animals to stock his zoo on Jersey."

After attending Hitchen's all-girls comprehensive school, Michelle went on to Oxford's New College and graduated in 1988 with both a BA and an MA. "I read pure and applied biology. What is so different about our university courses (degree programs) compared to North American ones is that's all we do, and so I didn't have to do lots of other subjects. I read (took courses in) biology for three years, and so I got through the degree a little faster than my North American counterparts. Oxford degrees are always Bachelor of Arts degrees. They don't give out B.Sc. degrees, and so, regardless of the actual discipline you are studying, the degree you receive is a BA. The other thing about Oxford is that, in your final year, you prepare a dissertation that goes towards the Master's degree. Consequently, when you graduate, you received both a BA and an MA."

"When I left university, I applied for a job with British Petroleum, and I worked for them for two years in London as a political analyst, working on environmental regulations. I wrote briefings on environmental topics for management at the BP head office in London, and I thoroughly enjoyed doing that. It really gave me a broad understanding of international issues and distilling them down for management who perhaps didn't have a lot of exposure to some of the technical terms."

"I had joined BP in the fall of 1988, and between that fall and the next spring I saved as much as I could from every paycheck for a whale watching trip to Mexico. While I had done some trips in continental Europe with my parents, that was my first real overseas vacation on my own. My dissertation at Oxford had been on marine mammals, and so this was my chance to really get out in the field and to enjoy them on a holiday. I got to see whales up close and just loved that."

"Everyone always describes whale watching as an extended period of boredom followed by brief little spurts of excitement when the whale comes up and does something. Then it dives, and particularly with whales like sperm whales, there may be an hour before they are going to pop up again, and so that gives you a chance to sit back and contemplate everything. You start seeing things that maybe you wouldn't notice before, like the gulls that are flying around or the smaller seabirds, or you start looking around and maybe see a sea turtle pop up. You'll see the kelp and so many other things that people tend to dismiss, and so it gives you that appreciation of taking everything else in. I'm never bored when I'm outside. Even if there's nothing obvious around, you can still just sit back and actually start seeing behaviour whether it's just watching the sparrows and the starlings. It really is fascinating. There's a whole world out there, whole other levels of existence and life and family drama going on that we tend to just overlook. I remember once when I was probably in my early teens in England, getting so excited and dragging my mother outside because there was an ants' nest in the garden. The colony was becoming winged, and so they were all coming out and flying off. My mother rushed back inside to bring out a kettle of boiling water to them all. And I said, "No, Mum! Don't do that. I'm watching them. Don't kill them. From an early age, I was protecting everything."

"The following late summer/early autumn after my Mexico trip, I went to southeast Alaska on another whale watching trip. Because I was going through Alaska, I went by the BP office in Anchorage and introduced myself. They were very nice and took me up to the Arctic to the oil fields there. When I got back to London, I was just raving about Alaska, and that was right at the same time that BP was asking, 'Where do you want to go next?' because I was due for a posting. I wanted to go to Alaska! Fortunately, it just worked out that the one biologist from Alaska ended up transferring to a BP office in Scotland, and I took her position in Anchorage in 1990."

"Though based in Anchorage, I was working as an environmentalist scientist in the Arctic oil fields. Specifically, I was working on field programs that looked at the impacts of all development on Arctic wildlife communities, and so I got to work with caribou, grizzly and polar bears, and all the shore birds that are up there. It is also quite odd when you go to those remote communities, and they've got cell phones and satellite TV. They'd get Chicago TV stations and would be watching Baywatch, and the news from Chicago. It was just so incongruous. Like kids anywhere, the children would be going around their houses on in-line skates, but meanwhile their parents would be butchering a seal in the bathtub. It's an amazing amalgamation of different cultures."

"I loved the high north in Alaska as well and the remote communities. I was lucky enough to stay in quite a lot of the Inupiat towns in northern Alaska. You always get to stay in people's homes because there isn't much tourist accommodation and they are so hospitable. I've had caribou, walrus jerky, muktuk and whale blubber, which is definitely an acquired taste, especially when it is served with the skin still attached. I'm vegetarian, but when you go to communities and you're staying in people's houses and they're being so hospitable, obviously you do have to make allowances."

"When you're in Alaska, the first thing all your friends ask you at the beginning of the year is, 'Are you going "outside?"' which means, 'Are you going to be able to leave the state at some point during the year?' Alaska's a wonderful place for a biologist, but it's a little bit too remote. You just had to go "outside" for sanity's sake. We used to have weekends away to Seattle to go to the theaters because not a lot of cultural things ever came to Alaska. After being there for six years and thinking about it long term, I decided, 'No, Alaska probably wasn't where I was going to stay.' I like the North, and the wilderness and wildlife of the north, and so I really didn't want to go too far south. Canada seemed like an natural area to end up. I had a lot of biologist friends with whom I had worked in Alaska who were Canadian. They would come up for the summers and work in Alaska, and then head back south. Many of them lived in the Vancouver area and on Vancouver Island, and so I initially moved to Vancouver. However, I ended up missing the real winter weather too much. I like the mountains and the snow, and so, after a couple of years in Vancouver weathering the very wet grey winters, I moved to Canmore, AB where, for four years, I rented right in the mountains which was fantastic. In the summer of 2002, I bought a house in Cochrane, about 45 minutes east of Canmore. I still have a nice few of the mountains, but they are a little bit further away."

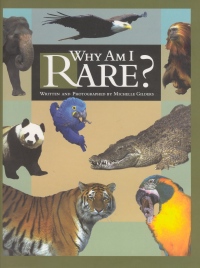

Michelle's first seven books were for adults, and she explains that her entry into writing "really sort of evolved out of my love of wildlife and travel. Initially, I starting off just wanting to record what I saw and experienced and to share it with family. I began doing it right from that first trip to Mexico. Actually, one of the photographs that's in Why Am I Rare? was from that first major trip. So, I really started the writing basically by keeping journals on my trips and then wanting to write them up afterwards. As I started to travel more and more and put those journals together, they really almost started to emerge into a book form, and I started writing my first book, Reflections of a Whale Watcher, which is on whale watching in Mexico. I had done some writing for a few magazines but nothing substantial, and so I was really going into the 'business' as a complete neophyte. I got the Writer's Yearbook and, using the outlines they have in the Yearbook , I started sending out query letters to publishers who seemed interested in nature and wildlife books."

"I collected an awful lot of reject letters, and I've kept everyone. I actually have a binder full of them. You have to keep those because you can never really survive being a writer if you ever take the rejection seriously or as a reflection on the quality of your writing. You just have to almost see them as 'little successes.' You've sent your manuscript out, and somebody's looked at it. OK, it's not right for them, but you've achieved something even if it's getting a rejection slip. Then you just use that as a motivation and say, 'Well, the next one might be different,' and you keep sending it out. I sent Reflections of a Whale Watcher out for a year before I got the call from Indiana University Press. Of course, I was working full-time at this point as well, and so the whale watcher book was really nights and weekends and not a lot of sleep during that time."

"My second book, Crossing Alaska, was interesting because, while I was at BP, the company sponsored the production of a book called Alaska's Arctic. It was published by Graphic Arts, and I got to know the editors and all the people who were working on that book. While I was still in Alaska, we started discussing the possibility of doing a book that coincided with the 25th anniversary of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline that runs from Prudhoe Bay down to Valdez. That was again right around the time that I was considering leaving Alaska and going freelance. When I actually decided to do that in 1996, we had already started talking about getting this book going, and then when I moved to Vancouver, we continued with it. That's the first book I did as a freelancer."

"While I was living in Alaska, though a very good friend of mine, I met wildlife photographer Art Wolfe who was kind enough to write a little blurb for the back of the whale watcher book. When I moved to Vancouver, I got in touch with him and told him that I was freelancing. I met with him again and his team who were based in Seattle, and we struck it off very, very well, and we started working on a number of book ideas. They already had another writer lined up for Water: World Between Heaven and Earth, who, for some reasons hadn't actually done the work. They phoned me up and asked, 'Can you write this book?' while adding, 'You have six weeks.' After picking myself up off the floor and panicking while thinking, 'Can I write this book in six weeks?' I accepted and did it.

"Water was basically a photographic book with a text of some 4,000-5,000 words. I wasn't provided with an outline, just the instruction to write what I wanted to write about the concept of water in all its forms. It wasn't a huge text by any stretch of the imagination, but it was certainly one that I wanted to get the text to feed into the photos and build on them and really get across the essence of what the photographer was trying to express. Art is such a wonderful photographer, and the images that he had really stretched the whole gamut from landscape to wildlife to native peoples around the world and their involvement with water. It was a challenging project but fortunately it went well, and I did some additional books with him after that."

"The Living Wild was a wonderful book. Art wanted to do a book that was a millennium type book, a book that would look at the state of conservation around the world at the turn of the century. He had five very well known conservationists from around the world put together essays that would address basically a looking back and then a looking forward. I worked as editor on The Living Wild and also put together all the notes on the photos and background on all species that were featured there."

"With Africa, basically I put together a series of essays on each of the major eco-systems in Africa, the rainforest, desserts, woodlands and wetlands, again tying them into Art's photos. What I wanted to do with these sort of books is to slip the science in so that people don't even notice they are getting some substantial scientific information. One thing that I've developed over the years as I've worked on these books is the practice of trying to send it out to as many people as I can before it comes out, people who are experts in their fields, to biologists all over the world. When I did The Nature of Great Apes, I sent that text out to people worldwide who were working on apes so that I could get their review. They could tell me any new information that hadn't been published or was just published. I also reviewed many articles in the peer-reviewed literature to try to get it as up-to-date as possible. Getting that technical review by people has been essential, particularly in books like the one on apes where I really want to make it a little different from other books that are out there on the same subject by trying to include the brand new scientific information."

Michelle's moving into writing for children came about, in part, because of happenstance. "Living in Alberta, I made contact with Dennis Johnson at Red Deer Press. I was actually talking with him about another book that I'm working on, a large format book on endangered species. Aimed at adults, it would have my own photos along with detailed information on each of the species. During the conversation, I casually mentioned to Dennis that I had 10 or 12 treatments of children's books in a drawer at home that I was wanting to do at some point. I had always been interested in getting into children's books, and what I said sparked his interest because Red Deer had been looking at expanding their children's book list, particularly in the nonfiction area. I passed the manuscripts over to him, and fortunately, they liked most of them."

"With my adult books, I know that if somebody's going to go out and buy The Living Wild, I've already got someone who's passionately interested in wildlife, but an area that I've always wanted to go into is where I can get kids who still have that open fascination. If you can get them at a young age, you can build on that for later on. The next book in the "Early Bird Nature Books" series will be on habitat, and, at the moment we have six planned in this series. I'm also working on another series of six for 7-12-year-olds that will all be coming out at once. The books in the projected "The Young Explorers' Series" will each examine a single species or group of closely related species: tigers, elephants, whales, penguins, crocodilians and marsupials. All the photography in these books will be my own."

In describing what she has found to be the greatest differences in writing for children as opposed to adults, Michelle says, "You really have to know your subject so well that you can get across your meaning in very short, brief little paragraphs and punchy sentences. With adult books, I think there's a tendency to wax lyrical and go on for pages and pages before you actually get to your point. As well, you bring in lots of ancillary information. I think that, in children's books, you really need to focus a lot more and get things across in as straightforward a manner as possible. You're still trying to make it readable and enjoyable and stimulating, but you've got to be a lot more focused."

"As I was working on the text for Why Am I Rare?, I developed the idea of using sidebars. When you're doing a book on endangered species or on any environmental subject, you're inevitably going to have to deal with terms like 'habitat,' 'species,' 'biodiversity' and 'extinction,' concepts that we take for granted that adults will know their meaning. But with kids, especially at the book's target ages, they hear all of these terms, but I don't know if they really have a clear understanding of what they mean. So, I would mention the terms in the text, and then the reader could go to the nice bright box and get a good, simple definition of what each term means. I wanted to make the explanations an integral part of the text rather than having a glossary at the end which is rather boring and which nobody might end up reading."

Why Am I Rare? concludes with a "What You Can Do To Help" section. Michelle had some very deliberate reasons for ending the book in this fashion. "Why Am I Rare? is obviously about species that are on the brink of extinction, and so there's a tendency to view it as a hopeless case. When there are animal species whose numbers are down to even less than a hundred in the wild, can we really do anything to save them? But there have been some great success stories, and I cover some of those in the book, situations where the animals literally have been on the brink of extinction but enough people have got together and worked and been able to pull them back. You can look at Gray Whales and Bald Eagles. So, yes, a lot of these animals are very, very rare, but that doesn't mean that it's too late, and the "What Can You Do to Help?" section is really aimed at taking that situation and saying, 'Look, an individual's actions do make a difference." Of the animals that are in the book, only a few are found in Canada, but I wanted to do a list at the end that would really involve kids to make them see that they can actually do things, themselves, that will make a difference for their local wildlife and hopefully encourage them to get more involved then in international issues. One suggestion is to adopt a species for their class project where I suggest that they pick an usual rare species. For instance, instead of picking the Giant Panda, instead, select the Puerto Rican crested toad, something different and something that's maybe hard to find information on. One of my pet peeves on wildlife issues concerns people who let their cats out at night because cats are tremendous predators and do an amazing amount of damage to small bird and small mammal populations, and so I want kids to realize that something as simple as keeping their cat indoors at night will help protect wildlife in their areas."

The end papers of Why Am I Rare? consists of a closeup of a giraffe's skin. Says Michelle, "I love taking photographs like that. I love the abstract and artistic photos. I take a lot of patterns. I think eventually there's going to be a book on patterns, shapes, and unusual ways of looking at animals. I also have a large number of "butt shots" as you can see on pg. 32 of Why Am I Rare? As soon as I took that picture, I thought, 'I know where that's going to go. That's the last picture, and it's the "end" of the book.'"

Michelle admits that "I do tend to get wrapped in the research part of writing. That's one of my favourite parts - just developing the ideas, searching out the information, making the contacts around the world and asking questions of these people about what things I should include. You could keep doing that forever. I also have to stop myself from wanting to include everything. Even doing a book like Why Am I Rare? there were so many other things I wanted to include, but you have to set boundaries. I was very lucky to work with a wonderful team of people in putting that together, and my editor, Peter Carver, who kept me under control about what things I could leave out. I think that, as an author, whenever you look at a completed book, you notice all the things you left out, but you have to remember that your reader won't know and that it's not going to really detract from the final book."

"I think with the age range that Why Am I Rare? is aimed at, the younger kids are obviously going to be looking at the pictures. They may be sort of skimming it, or maybe it'll be read to them. The older kids will get a lot more out of the text, and the even the older ones will then be interested on going on to the internet and doing a little bit more exploring. I've included some web sites at the end of the book, but I'm going to be building a companion website which will have a lot more links to other sites on the internet."

While Michelle is also a photographer, she observes that "trying to actually get established as purely a wildlife photographer these days and to make a living at it is virtually impossible just because there's so many great photographers out there. You're facing the professionals on one side, and then you've got all of the amateurs out there with the great equipment who are almost willing to give their images away. I've sold some images to CD-ROMS and calendars, and when I've done magazine articles, I've often had my own photographs to be used there. I don't really do magazine articles much any more because the amount of work I want to do to make it a good article is just too much for the money that's involved. Combining my photography with own writing is really how I want to develop things in the future."

"Over the years with the trips I've done, I've managed to build up a pretty good library of probably around 30,000 images. Working with some of the great photographers that I've worked with, people like Art Wolfe and David and Marc Muench, I've absorbed from them the technique and have tried to learn from them whenever I could. In these days with the type of equipment that's out there, anyone can be a photographer. I think one of the major differences between the amateur and the professional is that the professional has to have the eye for framing the picture. The other main distinction between an amateur and a professional is that the professional can shoot several thousand rolls a year whereas the amateur isn't going to be able to shoot that many. As a professional, if you spend the time and are willing to burn the film, you'll shoot lots of rolls and hope that you'll get just a handful of images. Amateur photographers tend to expect to get a high proportion of good shots. If an amateur shoots a roll of 36 and gets one back that's any good, they think, 'Oh, that's awful,' but, for a professional photographer, as long as that's the shot you're going to end up using, then that's great."

Michelle also works as an environmental consultant. "I still do a lot of oil and gas consulting, and so that's the 'real' job. But it's freelancing, and so I can pick the projects that I want to work on and do it that way. It gives me the time then to work on books. The two meld quite well because, as we all know, books can take a long time to come out, and so usually I have a long lead time that I can then work other things around it. If I need to concentrate on consulting for a while, I can do that for a few months and then go back to the books because I know what the deadlines are. I have my own environmental consulting firm, Natura, and then I work on specific projects through LGL Limited who are based in Sydney, BC."

And, if writing and consulting activities haven't kept Michelle busy enough, she also has served as a trip leader on various expeditions, "I've done some guiding to Alaska and to Antarctica a couple of times. It's one of my favourite places. These cold places, like Antarctica, the Falklands and the South Georgia area, are some of the most amazing places in the world. The wildlife is phenomenal. You can go to South Georgia and see a King Penguin colony of a half million birds. It's unbelievable, and, of course, because the animals are living on an island with no terrestrial predators, they have no fear, and so you can walk up to them. Actually, they'll come up to you and stare up at you. The young penguins will whack you with their flippers because they want to be fed. They think you're just a really big penguin. If you want to really confuse penguins in South Georgia, you just start walking along the beach while acting like a penguin, and they'll start following you."

"South Georgia's a remarkable place because it sort of helps you put everything in perspective. It's a place that has had a terrible history because it used to be a major whaling station. In the last century, tens of thousands of whales and seals and penguins were killed there for their blubber and oil. You can see the remnants of those whaling stations, and so you've got this strange contrast between these breath takingingly beautiful vistas and wildlife and then the rusted remains of harpoon guns and rendering areas for whales. You end up with a lot of different emotions when you're there, just experiencing it all and realizing how close we came to losing a lot of these animals."

"I've also done trips to Alaska and Russia, basically just across the Bering Straits from Alaska. My job is to explain what people are seeing and give a little bit of a background on the biology of what they are seeing. Usually I'm working with local guides in the area as well who know the specifics, and I'm there as the general interpreter. I do a lot of wildlife photography during the trips, but sometimes guiding can get in the way of getting the pictures that I actually need for specific projects. I definitely like the guiding and hope to do some more in the future, but again, it's trying to find the time to fit all of that in."

Single, Michelle shares her home with a parrot and a rabbit. The parrot, an African gray, is named Darwin, "which, of course, is the classic name for a biologist. Darwin's three-years-old, and he's definitely my 'child.' He follows me everywhere, and he's a good disciplinarian actually because, first thing in the morning, he'll be waiting for me to get up. If I'm late getting up, I'll start to hear him whistling and his voice going, 'Good morning. Good morning.' When I get downstairs and uncover his cage, then it's, 'Breakfast, fresh water, breakfast, fresh water.' As soon as he's had breakfast, then he starts his 'Want to go the office.' I have to take him up because he loves to go to the office. He hasn't quite worked out weekends. If I ever try to actually not work on a weekend, he still wants to go to the office. He will wander down the hallway and start climbing the stairs. He gets tired about half way up, and so then he'll just stop and wait for me. Darwin's wings are lightly clipped so that he can't get any lift, but he can glide and so he gets around pretty well."

"I also have Dillon, a pet Dutch cinnamon rabbit, and Darwin talks to him. Darwin will fly over to him and go, 'Dillon, what you doing?' and then poop on him. The poor rabbit's like, 'Again?' Very talkative and interactive, Darwin has a vocabulary of about 350 words. He knows what he wants, and he'll ask for foods by name: 'Want banana, want banana.' If you try to give him something else, he'll throw it away and just say, 'Want banana.' Darwin also loves pasta and fish and chips, and he gets very excited when he sees I'm making the latter. And just like a child, when he doesn't want to do something, it's, 'No, no. Don't, don't.' He knows different times of the day. When it gets to be about six or seven o'clock in the evening, he'll start flying over to me at my desk saying, 'More tickle, more tickle,' his way of saying he wants to go downstairs and have some playtime. So Darwin's good at getting me up to the office first thing in the morning and then getting me to leave the office in the evenings."

Darwin's the model for the logo for the "Early Bird Nature Books." "I wanted a bird to be the logo although what's there looks a little bit more like a Scarlet Macaw in its colour than an African Gray. At some point, I'm going to have to take Darwin along to a book signing. I think he'd go down as a treat though he probably wouldn't say anything. I have some friends who don't believe he talks. If there are people around that Darwin doesn't know, he'll be really shy and quiet, just taking everything in."

With everything she does, Michelle obviously needs to be well organized in order to be able to write. "Obviously, in a lot of cases, the consulting has to take priority because that's the money-making part of my career, and so, when I have projects come in, that work definitely takes priority but usually I can fit it in around the deadlines that I have for books that are coming up. If things are in conflict, then that just means I'm up really late at night working on both, but usually everything works out ok. Even if I'm consulting, I do try to spend a little bit of time each day on a book, even if it's just thinking about it. I'm a firm believer that writers are 'working' at their writing all the time, even if they're not actually writing. For me, when I'm developing ideas for a book or just trying to think it through, the time where I'm just sitting thinking about it is often the most important time. Even when I'm working on other things, in the back of my mind I'm thinking about a problem I have. "How I'm going to get a particular piece of information across in an accessible way, or what species I'm going to cover?' It's the usual thing where, in the middle of the night, I'll wake up, 'Oh, I've got that idea' and quickly write it down and get back to it later."

Michelle is also a list-maker. "I think that comes from the background I had in working for industry for eight years. I make lists of what things I've got to do, and I basically plan out the things that I want to achieve during that week. I also think I'm the sort of person who makes lists just so that I know I'm going to be able to cross certain things off. 'Yes, I've accomplished that. It's done.' At the moment, my list has things like 'organize slide data base' (a year long topic that I'm going to have to deal with, but eventually it will get done) and 'Thank-you letters' to the zoos that I've been shooting at."

"When you're working on books, everyone always says, 'Well, aren't you afraid that when you're finished one, that's it. You're not going to have any more ideas?' For me, it's, 'No, there's no shortage of ideas.' On my computer, I keep a list of 40 or 50 book titles of things I would like to do at some point. When I'm working on a book and I finally get it off to my editors for the 'magic' that they work on it, I'm already thinking about the next one and the next one so that, when the book comes out, I'm already working on maybe even two or three more. So far (touch wood), there's been no lack of ideas of things I want to cover. I think one of the reasons I became a writer and a photographer was that it's a wonderful excuse to travel, and it's a wonderful excuse to buy lots of books and do a lot of research, and to me there's nothing better than that. When I was working in Alaska and my friends discovered I managed to deduct my trip to Tahiti as a business expense, they were just so jealous, but I published some of the photos and others will be used in future projects."

"I think one of the problems that writers face is that, after a while if you haven't actually written anything, how do you then get back into it, and you hit that wall. I don't really call it writer's block. It's sort of inactivity. There's a wonderful book by Anne Lamott, Bird By Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, which is about writing. The analogy the author uses is that her bother went up to their father one day and said, 'Oh, I've got a huge school project on birds, and I left it so late. How do I do it? ' And the father's advice was, 'Just take it bird by bird.' Using that advice, I'm not suddenly thinking, 'Now I've got to write six children's books by spring.' It's, 'I've got to write one spread today, and then the next spread the next day. Over several weeks, I'll have the first book done.' If you just break it down, that really helps to frame for the day what you're trying to do."