Deborah Ellis

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

Books by Deborah Ellis. This article is based on an interview conducted in Toronto on February 28, 2003. While some biographical sources indicate that Deborah Ellis was born in Paris, Ontario, she corrects that information. "Actually I was born in Cochrane, Ontario, up near James Bay on August 7, 1960. I lived up in Moosonee right close to James Bay for the first couple of years of my life. My parents were working at a hydro outpost up near Abitibi Canyon which doesn't exist any more, and then they moved south when I was a little kid. I have one sister who's two years older than me. All my public schooling took place in Paris."

While some biographical sources indicate that Deborah Ellis was born in Paris, Ontario, she corrects that information. "Actually I was born in Cochrane, Ontario, up near James Bay on August 7, 1960. I lived up in Moosonee right close to James Bay for the first couple of years of my life. My parents were working at a hydro outpost up near Abitibi Canyon which doesn't exist any more, and then they moved south when I was a little kid. I have one sister who's two years older than me. All my public schooling took place in Paris."

As a child growing up, Deborah characterizes herself as "a social isolate. There's not a whole lot to say about it. Loners are loners, and that's kind of a universal thing I guess. People feel like they're on the outside, and they don't have a sense that they can change their circumstances. They just tend to hover around the outside and that doesn't change. I was pretty much like that right the way through school. However, I had a rich fantasy life, and I loved to ride my bike around the town, build forts and do stuff like that on my own and head off on my own. It was good growing up in a small town because I could just take off for the day, pack a lunch and disappear into the hills behind the town, and that was wonderful. There's an old graveyard up there where the founder of Paris, Hiram something or other is buried, and I used to ramble around in there, and so that was very cool."

"As a child, I was also a big reader. I grew up in a small town, and so my favorite books took place in New York City, books like Harriet the Spy and a marvelous book by James Lincoln Collier called The Teddy Bear Habit that's just been re-released in paperback. It's just a knockout book about these rude kids. Valley of the Dolls and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn were also favorites. In Valley of the Dolls, one of the characters leaves a small town and makes it big in Manhattan. I liked E B White because his writing is so beautiful, so poetic. He says so much in just such a short phrase. I also liked Lewis Carroll I guess because it's all so much fun. I think Dickens is absolutely remarkable, stunning. I reread him, and I like to memorize his poetry. Even now, it kind of entertains me during long staff meetings."

"I joined the Peace Movement while I was still in high school. The atomic scientists had this clock that measured how close we were to atomic war, and we were three or four minutes to midnight back in those days of the late seventies. Even before Regan, we were not doing well. There was a campaign that came to talk to the Paris high school, and I joined with the campaign. As soon as I finished high school, I got on a bus and went down to Toronto and worked with them full time. It was a volunteer organization. We had jobs, and we all lived in this house and worked on politics as well as just keeping ourselves going."

Deborah's involvement in the feminist movement came a little bit later, she explains. "This peace movement group was an organization of men who, by and large, were jerks. Because I had been so isolated, it took me a while to clue into the fact that these guys were jerks. And it took some really strong women coming into the group and telling them off and waking me up. Sometimes I need a real wake up call before I get things, but once I got it, I got it and got out of there."

In response to the question, "When did you know you wanted to be an author?" Deborah replies, "Oh, when I was about 11 or 12. I had been writing for a long time more or less seriously, but being a writer was always something that seemed like a very special thing to be. I could also pretend that people weren't talking to me because I was scribbling in my book rather than the fact that I was not a very friendly kind of a person. Reading great things inspires you to write great things. I got bumped up to high school English when I was in grade eight, and I did a couple of years of high school English back then. That kind of stalled because, when I was 14, I got put into a psychiatric hospital for a couple of years. I used to excel in public school, and then I kind of lost interest and never gained it back academically, but I did manage to graduate." Queried if the experience of being the youngest student in high school English was another isolating experience, Deborah responds, "Yes, but it was also great because once again I could pretend that people weren't talking to me because I was too young rather than because of the fact that I was just not very friendly. It added to my delusions of grandeur I suppose. It got me through it."

Like many authors who seemingly appear to be overnight successes, Deborah describes her route to publication as "long and arduous. Lots of rejections. Tons and tons of rejections. I'm not the kind of writer who sort of picked up writing for publication quickly. It seemed to take a long time to clue in on how to do it. Back when I was 11 or 12, I'd send stuff off and I'd keep sending stuff off. I'd do stupid things such as sending suicide poems to Good Housekeeping magazine. It was no surprise that they got bounced back pretty quickly. I didn't approach getting published with any kind of smarts. It was a long road, but that's the way it is for most writers I think. I guess every time I'd get a book rejected, I'd always have the sense that maybe the next one or the next one after that would be the one that would do it, and that I'd finally break through. But you never know. I could spend the next 10 years being rejected again. It's not a certain profession in any sense."

The writing Deborah did as a juvenile she characterizes as "really bad, all of it, but all different forms, plays, everything." Discovering places to send her writings came about "by chance. I'd see an ad for a contest perhaps, or I'd see poems in a magazine and then send poems into that magazine, things like that." While Deborah no longer recalls what was the first thing she authored that was published, she does remember that when she was about 25 she "wrote a play that won a competition that paid me something like $1500 which was a huge amount of money and so that was a big deal for me." She acknowledges having an adult novel published by a small publisher in San Francisco that "sold seven copies, maybe 12. It's about two women in a small Canadian town who fall in love. They're working against the Ku Klux Klan that has invaded their town, and so it's kind of a political love story kind of thing."

Deborah describes her transition to writing for children as "pure chance. Groundwood was having a contest for people who had never written for that age group before, and that was me, and so I wrote a book to throw into the contest. If they'd had a contest for animal stories, I would have written an animal story. It doesn't really matter. These days I'm mostly writing for that middle reader group which is an exciting age group actually because these kids are not yet sucked into the vortex of the soul sucking world of adulthood and adolescence leading up to it. They still have a chance to be their own people before the system and all that gets to them, and so that's an exciting time in life, a time when they can really make choices about who they are going to be."

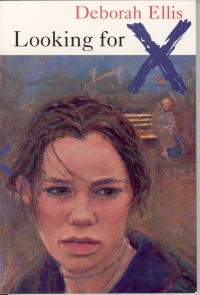

In writing a book, Deborah says she usually starts from a question. Her first book for juveniles, Looking for X "came from the question, 'What would it be like to be the daughter of a stripper?' I can't remember why I was thinking of that question. I knew I had to write the book for the competition, and maybe I was just going around and around in my head of things that would interest me, questions I needed answered, and that was the one that my brain settled on, and the rest of the story came out of that. I spent a lot of time in Regent Park, getting a sense of the place. I think that's mostly what I did as research."

In writing a book, Deborah says she usually starts from a question. Her first book for juveniles, Looking for X "came from the question, 'What would it be like to be the daughter of a stripper?' I can't remember why I was thinking of that question. I knew I had to write the book for the competition, and maybe I was just going around and around in my head of things that would interest me, questions I needed answered, and that was the one that my brain settled on, and the rest of the story came out of that. I spent a lot of time in Regent Park, getting a sense of the place. I think that's mostly what I did as research."

Though Looking for X was actually the runner-up in the Groundwood Twentieth Anniversary First Novel for Children Contest, it did win the 2000 Governor General's Literary Award for juvenile English fiction. Deborah recalls the experience. "It was weird. When you get the GG Award, they harass you about your clothes for weeks ahead of time to make sure you're dressed properly, and so I spent so much time worrying about whether or not I was going to have to wear a dress. Finally I said, 'Screw this!' So that took up all the pre-winning worry, and afterwards I got three books rejected one after the other, and so winning a GG didn't seem to make a whole great deal of difference to my life. The rejections brought me down to size. If I was getting a swelled head from the award, I got deflated very quickly."

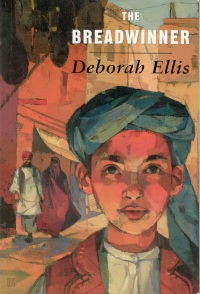

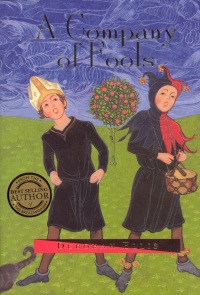

Looking for X is very much rooted in the contemporary world as are Deborah's three novels set in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Although Deborah's previous writings have touched on a variety of genres, she says, "I've never been a fan of fantasy or science fiction. It's never interested me at all." Even her recent foray into historical fiction via A Company of Fools, Deborah again says came about "only by chance. It's the story that kinds of grabs me, and the Plague was such a fascinating thing to write about anyway so that's why that happened. I did The Breadwinner after Looking for X and that got accepted quickly, and then, as I said, the three I did after The Breadwinner, Groundwood sent back very quickly. One of them was the plague book, The Company of Fools. The other two weren't worth it anyway, and I don't know why I wasted my time. An adult book, Women of the Afghan War, came before The Breadwinner. It was published by an academic press, and so the book's hugely expensive and hardly anybody who matters can afford to buy it."

Deborah had established Women for Women in Afghanistan when the Taliban took over Kabul. "I went to Pakistan in the fall of 1997 to see how we could be of more use back in Canada. I thought that, if we could meet with some of the folks directly over there, we could find out what their needs were. I stayed in the camps a lot of the time or in the slum areas in Peshawar, a border town in Pakistan. One of the women who translated for me used to be the principal of the largest girls high school in Kabul until the Taliban chased her out. She was quite remarkable. She'd traveled all over the world for women's rights for Afghanistan during the time of the governments before the Taliban."

Deborah also visited Moscow in the spring and fall of 1998. "I had heard of this organization in Moscow that was for Soviet women who had been part of the Afghan war, and I wanted to bring their stories together with the Afghan women's stories because I thought it would be interesting. I first went over there to do initial interviews so that I hopefully could get a book contract with that as a basis. Then, when I went back the second time, it was with the contract to do the interviews directly for the book Women of the Afghan War. The Russians had a lot of women working alongside the soldiers. They were there as cooks, engineers, medical staff, and clerical staff. They were not officially part of the army but were subject to army discipline. They were basically under orders to be there, but they weren't eligible for army benefits when the war ended. I met a lot of the Afghan women, wives of those who fought against the Russians, in Pakistan. The ones I met in Russia were current refugees. There's an old soviet holiday camp about an hour outside of Moscow, and it's just chockablock stuffed full of Kurdish and Afghan refugees."

"I spent a lot of time with the people there getting their stories. I went into it kind of naively because I thought that we could bring some of the Russian women and some of the Afghan women together while I was there and have a dialogue, but there wasn't any possibility of that. The Russian women, even with all that they had been through since the war and during the war, still thought of the Afghans as people who needed to be civilized and the Russians were there in order to civilize them. Even with all that they had been through, they hadn't been able to lift that barrier to understanding the other side. The Afghans in Russia had such a difficult time because, whenever they went outside, they were subject to police harassment. Since they didn't have any papers, they'd get arrested and have to use bribery to be released. So I was never able to bring them together."

While The Breadwinner is based on a real character, Deborah has never actually encountered her. "I just met the mother. There was an Afghan women's organization operating in Pakistan at the time, and they had smuggled some women out of Afghanistan to attend an international Women's Day celebration. The Taliban had said that they would cut the legs off anybody who celebrated Women's Day in Afghanistan, and so these women bravely got themselves out of the country for a few days. I got to talk to them, and one of them was the mother of a girl who was still back in Kabul. The woman's daughter had cut off her hair and disguised herself as a boy so that she could earn money for the family. She was doing this incredible thing. I couldn't even imagine it, and it just stunned me when I heard about it."

While The Breadwinner is based on a real character, Deborah has never actually encountered her. "I just met the mother. There was an Afghan women's organization operating in Pakistan at the time, and they had smuggled some women out of Afghanistan to attend an international Women's Day celebration. The Taliban had said that they would cut the legs off anybody who celebrated Women's Day in Afghanistan, and so these women bravely got themselves out of the country for a few days. I got to talk to them, and one of them was the mother of a girl who was still back in Kabul. The woman's daughter had cut off her hair and disguised herself as a boy so that she could earn money for the family. She was doing this incredible thing. I couldn't even imagine it, and it just stunned me when I heard about it."

"Since then, I have heard that there were quite a few kids who have done that same type of thing. I also heard a number of tales about kids who had been taken off the street and who, when they're found or when they show up, have scars. There's a kidney missing, and they die shortly afterwards because it's not done properly. Refugee children are also kidnaped. Boys, because they are small, end up as jockeys in the camel races in Saudi Arabia. They are basically used up and then discarded. Girls get sold into prostitution and domestic slavery and that kind of thing. It would be interesting actually to do a book about that to find out who these kids are." Deborah says that each of the principal episodes in The Breadwinner came from "people telling me that they had witnessed it or they had done it themselves. The only thing that came from another source was the bone digging in the graveyard which I got from Time magazine. I hadn't actually met anybody who had done that."

The Breadwinner is not just selling in English speaking countries. Deborah notes that there is a South American edition in Spanish, and the book has also been purchased for markets in Italy, Greece, Denmark, Germany. Norway, Japan, Croatia, India, Sweden, and Switzerland. While Deborah comments that "a lot of the international contracts for The Breadwinner were signed before 9/11 happened," that tragic event did have some publishing impact. "For example, England bumped up the date of publication, and they turned it around in like three weeks. And then it just flew off the shelves almost before it got on the shelves."

To date, according to Deborah, The Breadwinner has not been perceived as being anti-Islamic in content. "If people have seen that, they haven't talked to me about it. I know that in the Afghan community in Toronto and other Afghan communities it's been very well received which has been a good thing for me to hear. However, I do get criticisms sometimes from adults saying that children shouldn't be reading about this 'tough' stuff, but phooey on them. Who cares? That's the way it happened."

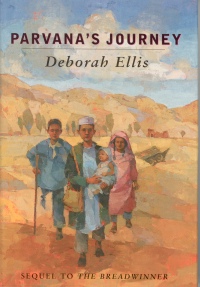

"The Breadwinner's sequel, Parvana's Journey, came more out of my imagination and trying to imagine how these kids would survive in this landscape of war rather than from incidents that I'd actually heard about. My dad wanted a sequel to The Breadwinner, and he kept asking when I was going to write it, and I said, 'Alright, Dad, I'll write the thing.' Then he wanted a third one. So, one more for you, Dad, and then that's it. I'm done. A lot of Mud City's money is going to the Street Kids International organization because the story is a little different. It's more an urban survival story."

"The Breadwinner's sequel, Parvana's Journey, came more out of my imagination and trying to imagine how these kids would survive in this landscape of war rather than from incidents that I'd actually heard about. My dad wanted a sequel to The Breadwinner, and he kept asking when I was going to write it, and I said, 'Alright, Dad, I'll write the thing.' Then he wanted a third one. So, one more for you, Dad, and then that's it. I'm done. A lot of Mud City's money is going to the Street Kids International organization because the story is a little different. It's more an urban survival story."

The royalties for both The Breadwinner and Parvana's Journey Deborah has generously donated to Women for Women in Afghanistan. "I got the statement from the group out in Calgary that gets the money, and it's presently over $150,000. I think it would have been an act of 'incredible generosity' if the money had first come to me and I had to continue to make the decisions to hand it over. But it isn't that big a deal because all I figured I was handing over was the $3,000 advance that Groundwood was going to give me. Beyond that, I hadn't expected the book to go anywhere. It might have been harder if I had to make that decision today. But you know, I have a day job, I don't have kids, I don't have concerns, and hopefully I'll keep writing, and continue to make money."

"So, donating the royalties is not that big a deal, especially when I ask myself the question, 'What would I have done with the money here?' I could have done some neat things for myself, but, over there, we've built women's centers, we've built schools, we've put kids into education, and we've put women to work. We've done so much more over there than I could have done here, and, hell, that's fun. That's a lot of fun. When's a schmuck like me ever going to be able to do that in the world? And that's just a real kick! We're spending some of the money in the camps as is needed, and now we're being able to start doing stuff inside Afghanistan too. There's a large number of people going back to Afghanistan. I don't know if it's slowed down or not. Probably over the winter it has, but also we're hearing some really disturbing things from the areas outside of Kabul where the warlords are in power and where they are burning girls schools to the ground again and threatening women with the same old things that the Taliban did. It's hard to say what's going to happen."

"So, donating the royalties is not that big a deal, especially when I ask myself the question, 'What would I have done with the money here?' I could have done some neat things for myself, but, over there, we've built women's centers, we've built schools, we've put kids into education, and we've put women to work. We've done so much more over there than I could have done here, and, hell, that's fun. That's a lot of fun. When's a schmuck like me ever going to be able to do that in the world? And that's just a real kick! We're spending some of the money in the camps as is needed, and now we're being able to start doing stuff inside Afghanistan too. There's a large number of people going back to Afghanistan. I don't know if it's slowed down or not. Probably over the winter it has, but also we're hearing some really disturbing things from the areas outside of Kabul where the warlords are in power and where they are burning girls schools to the ground again and threatening women with the same old things that the Taliban did. It's hard to say what's going to happen."

A Company of Fools had an unusual genesis. "I was working on another novel when I bumped into the term, 'a Company of Fools.' I like talking about the book, A Company of Fools, because it's such a happy book in comparison to the war stuff. It's so much more fun. It's a little bizarre to say that it's fun, but I've never met any plague victims, and so that makes it a little easier. I was actually planning to write another book, and I was doing some research for it when I came across a little line that talked about this group called 'A Company of Fools' that entertained people who were dying during the Black Plague in 1348 Paris. The title, itself, is so fabulous - A Company of Fools - it's just great, and I knew I had never heard of any books of what it had been like to be a child during the Black Plague. I wanted to find that out, and I wanted to put the kid in with this Company of Fools so I could find out what their lives had been like and how people had responded to them. I had to do a lot of research for A Company of Fools, but that was so much fun. The Middle Ages is so great, and you could spend days reading up about just the food alone."

"Writing A Company of Fools was a real wild ride because it took me a long time to get the voice right and to get the story right. I have a great deal of affection for that book. I had many false starts, and I rewrote it completely many times just because I couldn't figure out exactly what the story was and who should be telling it essentially. Sometimes it's really hard to figure that out, and sometimes you know right away. I never found another reference to the Company of Fools. The whole book is all created. I based the monastery on monasteries I had seen over there with the labyrinth in the floor and things like that. The story's a lot of fun, even with all the death. Who would not want to play ghost jump? It's such a fun game. And they don't let you do that in Westminster Abbey. I know they don't because I tried it. They're pretty strict about stuff like that."

In talking about her writing process, Deborah says, "Usually the beginning part goes through a whole bunch of different drafts while I'm trying to find the voice and the structure of the story. Then, at a certain point, it becomes an endurance contest, almost like an end run. I'm usually able to do the final few chapters almost with one draft because, by then, I know so much about what's happening and what's going on and whose there that I don't have to keep rewriting it. When I'm writing, if I'm trying to 'control' the characters, the book doesn't seem to go anywhere. Usually, if I'm blocked, it's because I'm trying to force a square peg into a round hole by making somebody do something that they're not supposed to be doing."

"For example, there were lots of times in A Company of Fools when I tried to get Micah to do something that he was just not interested in doing. Micah's another character I would like to have been. Isn't he great? He's kind of like the Ghost of Christmas Present. That's how I see him - just larger than life and just embracing everything that comes to him because it's probably not going to be there tomorrow. I like the scene where Micah and Henri are in the infirmary and Micah feeds Henri the soup and he sort of needs to be told almost how to do that. I like it when people in books treat each other well. I don't think you necessarily have to have people hurting each other all the time for it to be a good story. There can be just as much drama the other way. In Parvana's Journey, I think Assif brings out the good parts in Parvana because she get a little boring in my mind, and so she needs somebody like Noria or Aasif to rub up against her."

"For example, there were lots of times in A Company of Fools when I tried to get Micah to do something that he was just not interested in doing. Micah's another character I would like to have been. Isn't he great? He's kind of like the Ghost of Christmas Present. That's how I see him - just larger than life and just embracing everything that comes to him because it's probably not going to be there tomorrow. I like the scene where Micah and Henri are in the infirmary and Micah feeds Henri the soup and he sort of needs to be told almost how to do that. I like it when people in books treat each other well. I don't think you necessarily have to have people hurting each other all the time for it to be a good story. There can be just as much drama the other way. In Parvana's Journey, I think Assif brings out the good parts in Parvana because she get a little boring in my mind, and so she needs somebody like Noria or Aasif to rub up against her."

Regarding her own approach to writing, Deborah observes that "Kids in school are taught to plan their writing. That's just a lie. I think it's some way the teachers have of marking them, but that's all it is. It's just an exercise. It doesn't have anything to do with writing. Also, if you plan your story out, you already know what's going to happen, and so why bother to write it? You've already answered all your questions. Consequently, I don't plan too much. You have to kind of let it grow."

To date, Deborah has handwritten her manuscripts because, as she explains, "I hate typing. I did that very badly for a while as a temporary secretary. No employer could have stood having me employed with them for very long because I just didn't care enough to do a very good job. For instance, when I was on reception, I'd cut people off if I didn't like their tone. I'd misfile things out of spite. Consequently, I wasn't very good at being a 'temp.' I have just bought a used laptop, and so I'm trying to figure out how to turn it on."

Questioned about what aspects of her childhood have come into her writing, Deborah points to Looking for X. "I think Kyber is who I would have liked to have been. She's rude and independent and angry and doesn't care what people around her, that she doesn't care about, think about her. But she's also fiercely loyal to the people that she does care about. Those are all great qualities, and so I wish I had been more like Kyber. I was much too wimpish and not nearly as strong as I could have been."

Groundwood sent Deborah to Israel and the Gaza Strip to research a book, a nonfiction oral history, about Palestinian and Israeli children. Deborah explains: "Women of the Afghan War is all oral history essentially, and I really like that medium. Studs Turkel is one of my heroes, and I think oral history's an incredibly powerful medium because it gives a voice to ordinary people talking about their experiences in a way that shows that they are not ordinary or unimportant. I don't think there has been a lot of oral history of kids talking about their experiences, and I think that's something I'd like to do a lot of in my life ahead. I was over there interviewing Israeli and Palestinian kids about how they felt about the war and each other and their lives and all of that stuff. The book's to be out in the spring of 2004."

The summer of 2003 was to see Deborah off to Africa, likely Malawi and Tanzania, to do an oral history of kids whose lives have been affected by AIDS. Asked to explain how she connects with her human subjects, Deborah replies, "It's not that difficult. You start out with contacting a number of organizations through the networks here and over there. Then you just meet people, and they introduce you to other people, and they know other people. I did a lot of barging into places, just kind of walking in and blabbering until someone found me a child and chased me out of the room. In some cases I use interpreters. With the Israeli and Palestinian interviews, I just roped whatever adult I could grab to interpret for me."

"I'm doing the AIDS book with Fitzhenry and Whiteside. It's something I wanted to do because I want to know who these people are. I want to know who they are and why they're dying off at such an incredibly criminal rate. In some ways, collecting their stories and finding out who they are before they die seems like an awful thing to do. In the absence of being able to stop them from dying, at least it's a sense that we can show to the world that, yah, they existed. They were here, that it meant something, and that they were alive. It's just criminal that they are dying because they don't need to be dying. This is not necessary. It all goes back to adults. War continues because people make money off of it. Hatreds continue to ferment into war because somebody's selling them the weapons, and the situation in Africa continues because it is more profitable for someone to allow it to continue than to fix it. I mean, hell, we have this absurd view of children in this planet that some children need to be protected and coddled and cocooned, and, at the same time, we are very, very happy to let most of the kids around the world drink poisoned water. That's fixable. It's fixable to have clean water for everybody. It's fixable to stop the rampages of AIDS. We just don't want to do it. They're just not important enough to us."

"When you look at the reasons why people die of AIDS, the little bit that I understand, a lot of it is getting infections. The body isn't able to fight off things very well, and so, if someone is HIV positive and they drink bad water or they can't fight off malaria properly or they get some other kind of infection, that's going to kill them faster than it would over here. They don't have a proper diet, and again that weakens their immune system,. All of those things are fixable. We just choose not to. For example, malaria is on the rise because of war that forces people to move out of where they are usually living and live in places that are more heavily infested with mosquitoes, and so a lot more people die. You can trace so much of it back to simple profit."

"While I was touring, a kid out in Winnipeg asked me if I'd write humour, and it would be nice to get away from war and pestilence and stuff for a while. I've got some heavy books ahead of me, and so I'll have to think of something fun to do afterwards as an antidote. I have some ideas that would be fun." Looking ahead to more juvenile fiction, Deborah says, "I like the notion of kids as con artists. I have some ideas around that, trying to earn a living as con artists, and I think that would be fun to explore. I'd also like to do a sequel to A Company of Fools and have some kind of a Christmas story in mind, but I'm not quite sure what's going to happen with that. I'd like to bring both characters back together again somehow, and so I'll have to figure that one out."

Regarding her non-author life, Deborah says, "I work as a counselor in a psychiatric group home for women. My shifts are all over the place, Sometimes day, sometimes evening, sometimes night shifts." When asked when she finds time to write, Deborah's response displays the mischievous sense of humor which is also part of this committed social activist. "I find the time to write because, alas, I have no social life. Wait, that might not be the best answer - kids will think that I'm a loser. Better say something more profound, like we all find and make the time to do the things that are important to us."

On a more serious concluding note, she offers, "Writing isn't magic. I mean, hell, if I can do it, anybody can do it. Kids can do it. When they write down their stories, it means that people can read them 10 centuries from now and know who we were, and that's a wonderful, wonderful thing. What a blast! We can know what Plato and all those people were thinking back in those days, and generally they weren't thinking anything too terribly more interesting than what we're thinking now. We're thinking the same things and have the same questions."