Postscript: "I have indeed simplified my life (in some respects). While I'm still teaching my course at Ryerson and doing a little freelance writing on the side, I've left my position at Lorimer to spend at least a year concentrating on my second novel and a nonfiction book for yung adults about public space, which will be published by Kids Can Press in fall 2008." Books by Hadley Dyer.

Hadley Dyer

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

While Hadley acknowledges Halifax, NS, to be her "official" birth place on September 12, 1973, she says that location was more due to the fact that Halifax was where the "big" hospitals were. "I was raised in Kingston which is in the middle of the Annapolis Valley. When I graduated from high school, I moved to Halifax to go to university, and, because my parents moved to Halifax a few months later, I never really went back to the Valley until recently. I have a sister, Rachael, who's just a year older than I am, and I have a brother, Adam, who's about five years younger. Adam was our 'pet', and when he arrived, Rachel and I were like, 'Oh, good. Something to put makeup on.'"

While Hadley acknowledges Halifax, NS, to be her "official" birth place on September 12, 1973, she says that location was more due to the fact that Halifax was where the "big" hospitals were. "I was raised in Kingston which is in the middle of the Annapolis Valley. When I graduated from high school, I moved to Halifax to go to university, and, because my parents moved to Halifax a few months later, I never really went back to the Valley until recently. I have a sister, Rachael, who's just a year older than I am, and I have a brother, Adam, who's about five years younger. Adam was our 'pet', and when he arrived, Rachel and I were like, 'Oh, good. Something to put makeup on.'"

"I think I did always want to be a writer. Of course, whenever I had a favourite teacher I wanted to be a teacher. When I was kid, my dad was a lawyer, and, because I was very argumentative, I thought I might want to be a lawyer. Like everyone, I fantasized about doing other things, but I think from the time I was about eight or nine-years-old, I knew writing was something I would like to do if it was something that you can do when you grow up. My mom was very encouraging of my writing from the time I was pretty young. I didn't know if I was going to be able to be a full-time writer of books some day, but I thought I would want to do something with writing or words."

"We did a lot of writing in school. We had lots of contests - poetry, short story, and speech writing contests. In fact, one of my earliest memories of writing seriously was a poem I wrote in the fourth grade. I remember it because my teacher accused me of copying the poem. I also remember it because of my mother's rage at this teacher and also her pride in my poem. Because I knew that, because this was important to my mother, it must be important in a bigger sort of way."

"I was always taking care of children. My mother took care of my father's law partners' kids when we were growing up, and so we always had kids in the house. When I was a teenager, I nannied all the time, and, while I was in university, I did too. When I first went to the University of King's College, which is affiliated with Dalhousie University, I took journalism thinking, as so many writers do, that journalism is writing, and, of course, it's very different. I started working at Woozles, a children's book store in Halifax. Once I really started working at Woozles, I ended up going to school part-time. I think my career path was set almost from the moment I walked into Woozles because I started writing reviews for Children's Book News and then Quill & Quire. That then led to more writing, and I thought to myself, 'If I need the journalism piece of paper, there's a one-year program I can do,' and so I switched out of journalism and into a B.A. with a major in English. I really cut my teeth on children's literature at Woozles which was my first big job. I eventually became the assistant manager there, and I learned so much from Trudy Carey about not just what makes a good book but about how kids respond to books, why they like the books they do, and why people choose books "

"I then moved to London, ON, where my boyfriend was doing his Master's degree at Western. Again, I worked at a book store, Chapter's. It was a very good experience because it was their first big year. By the end of that year, however, the book selling landscape had changed so significantly, but during that year the president of the company would still come to store openings and events."

"After that year, I went to Toronto where I took contract work for a community newspaper at the University of Toronto. At the time, I was living on five dollars a day. I'd go to a Chinatown and get a three dollar dinner. I'd have half of it for lunch and then the other half for dinner. On January 2, 1999, just before my contract with the newspaper was over, I was hired by the Canadian Children's Book Centre as the library coordinator. Charlotte Teeple, the Executive Director, said, 'Your job is to be the in-house expert on children's books. You're the resource and the one we'll call and say, 'Which book has this theme in it?' or 'How many books has this person written?' My job was to read, and for three years I read voraciously. As well, I worked with Gillian O'Reilly on Children's Book News, and I managed some of the book awards that are administered by the Centre as well as the annual Our Choice publication. It was a very good experience at the Book Centre but very, very busy."

"When I was ready to leave the Book Centre at the end of 2001, I didn't know if I would go into the promotion side or the editorial side of publishing. I had been writing, and I had worked as an editor at this community paper. As well, Stoddart had given me an opportunity to do a project. Originally, I applied for the managing editor's position at Groundwood, but I didn't have enough experience. A few days later, Patsy Aldana called and said her marketing manager's position was available. Marketing and publicity weren't for me in the end, but I feel that, as with Woozles and the Children's Book Centre, I've been incredibly lucky experience-wise in my career. I was able to spend a year at Groundwood, arguably one of the best publishing companies in the country. I share Patsy's philosophies around the types of books that she publishes and why she does so. Being able to have observed Nan Froman, the managing editor, and Michael Solomon, the designer, at work firsthand has influenced everything I've done since."

"I was glad to have the opportunity to work at Groundwood even though I don't know if I was a great publicist. I had just started when the events of Sept 11th happened, and Groundwood had, I think, the only English language children's book about Afghanistan, Deborah Ellis's The Breadwinner, and here I was, the publicist. Suddenly we had the Washington Post and Time for Kids Magazine calling. There was a moment when we thought Deborah might actually get on Oprah, which led me to think, 'I've been here for four weeks, and I've peaked. I can retire because I've done it all!' It was definitely trial by fire but again an amazing experience to have."

"While I was at Groundwood, I had continued to do some freelance writing on the side. I'm always paranoid that everything's going to go away. Consequently, even when I had a full time job, I was still doing freelance writing while trying to write fiction also on the side. By the end of my first year at Groundwood, I was not only becoming aware that I was in the wrong department but also that I was getting really, really tired. By that time, I had already been working in the business for 10 years, but I was really burning out. When a half-time editorial position became available at Lorimer, I jumped at it. It was scary financially, and the first few months were difficult. At that point, I was also President of IBBY-Canada, and I thought, 'All I'm going to do is focus on learning my new job as I have a lot to learn, and I'm not going to accept any additional freelance work. I'm just going to do my new job. I'm going to work on behalf of IBBY (which was at that point was more like 20 hours unpaid a week), and I'm going to write my book.' Financially, it was disastrous, but, of course, I'm still reaping the benefit of that period. It was worth it in the end."

Asked how she learned to be an editor, Hadley explains, "I now teach an overview to children's publishing at Ryerson University, and the first thing I say to the class is that the way that I became an editor is probably not how they're going to become editors. I'm part of that last gasp of people who work in publishing or in journalism who didn't need a certificate to get in and where the sum of my experience had value. I was lucky that Jim Lorimer looked at the totality of my experiences and said, 'Yes, I would like an editor who has some editorial experience but also marketing experience and who has worked as a writer (as obviously you would learn a lot of editorial skills being a writer) and who's been a bookseller. Those are qualities I want to have in an editor.' Today, it is more common for someone to do their degree and then go and get a publishing certificate, become an intern and then an assistant editor and go from there. It's my career 'luck' that sort of brought me where I am."

"My course is just a half-credit, and it touches on everything. One week, for instance, we do editorial, on another, marketing, and another, rights, and so on. It's unfortunate that we can't do two different versions of the class with one being for people who know absolutely nothing about the publishing industry and another for people who are already in the business. Having the experience in class is sometimes handy. I had someone who worked in the rights department of HarperCollins, and I was able to pause and say, 'Would you say this is typical in a contract?' and she would say 'Yes' or 'No'. I love doing the course, but unfortunately so many of the class want to be editors, and they only have one week where they're getting into the guts of editorial work and a separate week on acquisitions. As I said, these days the typical route to becoming an editor is as I described, and the person would do a certificate which might include a course like mine followed by an internship. As for me, when I joined Lorimer, I wasn't a trained copy editor or proofreader, and these were things that I had to learn. So many editors go by the 'feel good' method. I knew how to craft a good sentence, but I had to make sure I knew why. Mind you, we do hire freelance copy editors and proof readers to handle a lot of the technical stuff. My job is really more acquisitions and substantive editing, but still I'm self-conscious about it, and so I work harder."

Hadley's first published book came about via Rebecca Sjonger who was an editor at Crabtree Books and another former Canadian Children's Book Centre employee. "I thought I would do more freelance magazine work once I had written a draft of my novel, and I had just got to the point where I thought, 'OK, I can do the freelance stuff now' when I received an email from Rebecca Sjonger saying, 'We're looking for some writers, and I think you could do this.' It was a wonderful arrangement while it lasted. Just from the perspective of managing your workload, it's much simpler to do two or four Crabtree books a year than eight or ten freelance articles where you're constantly pursuing the work and juggling multiple projects."

"I really liked working on the books, but as I said to my mom, it was really like being doomed to write science fair projects for the rest of my life. I recalled all those nights at the kitchen table with my mother standing over me going, 'Good students do outlines,' and now for a living I was doing outlines and redoing outlines." After doing a dozen books with Crabtree on a flat fee basis between 2004 and 2007, Hadley says, 'I was ready to focus on other things, but the Crabtree books were fun to work on.

"Crabtree would come to me, and they often give me an option for a couple of topics I could work on. Depending on the book, I was listed as a researcher or sometimes I shared authorship with Bobbi Kalman. Actually, as ana editor, I think I learned so much from writing those books.. Firstly, when you're a writer and you work with a variety of editors, you learn all of these different practices and what works and what doesn't and what's important and how you like to communicate. Crabtree was very, very good at taking what was sometimes very difficult information and making it accessible at a grade two, three or four reading level. I was always amazed that I could look at a section for quite a long time and work at it and work at it, and then I would send it in and say, 'Help,' and they would know how to phrase something or how to cut something down so that it was at the appropriate reading level. I learned a lot as an editor from observing the Crabtree editors. I found it to be very helpful now that I'm working on hi-lo books for Lorimer because I have learned the discipline of writing about difficult things for a lower reading level."

"If the topic was in an existing series, Crabtree would send me copies of those books so I could familiarize myself with their house style for that series. I would do the research and generate first an outline and then a manuscript. Sometimes, it went very smoothly, and I would do just one draft or two and we'd be done. Sometimes we had a topic that was a little more complicated, and it might take a few more rounds to get it right and to find a way to fit it into the format of that series. Again, it was very good discipline for me as an editor to say, 'Alright, we need a certain number of visuals. We need a certain number of captions. It needs to be at this reading level. If the topic doesn't fit exactly, well, we'll find a way to make it fit, or we'll have to find a way to adjust that format.' Crabtree would always bring in a consultant who would be an expert in that subject who would do fact-checking. Part of my job was to suggest the visuals for the book, and that makes sense because, when you've done the research, you know roughly what's available and what you need to see. I would make a long wish list of all the illustrations that they might want to include, but Crabtree had an in-house photo researcher who took care of that, and they would hire the illustrators themselves."

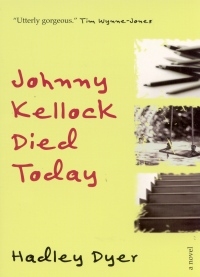

Regarding her first book of fiction, Johnny Kellock Died Today, which was named the 2007 CLA Book of the Year for Children Award and an Honour Book for both the CLA Young Adult Book Award and the TD Canadian Children's Literature Award, Hadley says, "I think I had the idea for this story back when I was living in Halifax about 10 years ago. I probably scribbled some notes to myself as far back as then. Then, when I was at the Children's Book Centre, I wrote a couple of chapters, but I really didn't start working seriously on it until I moved to Lorimer. With the half-time job, I was able to devote myself to completing at least one very bad draft of the book. I wrote that draft in three months, but that was because I had been percolating on it for a long time. Then I rewrote it four more times."

"I was very worried about how I would place the manuscript because I thought, 'All of these editors are my colleagues, and the last thing I want to do is to be at a committee meeting six months from now with five out of the six people around the table having rejected my manuscript.' I just thought it was a terrible position into which to put a friend in or an acquaintance. What I did first was make a list of the houses where I thought the book belonged. Then I thought about other things, such as suitability for a publisher's list, which editors I would like to work with, and who did I think could do a good job of promoting the book. While I was considering all these things, I had a friend working at HarperCollins. For at least a year, she'd been saying to me, 'Whenever you finish your book, give it to Lynne Missen. She's a wonderful editor, and you'd have a wonderful working relationship.' I knew Lynne well enough to phone her up, but not so well that she'd be in an awful position if she said no, and so I phoned and asked, 'Would you like to look at my manuscript?' I was very lucky that she said 'Yes', and we've had a wonderful working relationship. My friend didn't reveal that she knew me until after my book was acquired."

Asked if being an editor herself impacts the author part of herself, Hadley replies, "I think because I've worked in the industry and I've helped usher other people into publication, just having a book published is, for me, no longer enough. I've seen my name in print in newspapers and magazines and in the Crabtree books and that doesn't give me the same 'jolt' that it used to. To publish a book prematurely would destroy my editorial credibility. Ten years ago when I started writing seriously on the side, I just wanted to be published, and by the time that happened, the fear was, 'Is it good enough? Is my writing group right? Is my editor right? Is my mother right?'"

"I think that, because I was not in a hurry to get the novel published, I did hold myself to a certain standard. The HarperCollins production editor came to my class at Ryerson as a guest speaker, and she asked me if it was OK if she brought some of the materials from my book. I agreed, and she held up the original copyedited manuscript, and it was covered with electronic sticky notes from me to the editor saying things like, 'Do you think this is cliched? Is there a better word choice here?" But at the same time I was 'editing' myself, I needed the editors I worked with there. It doesn't matter how much experience you have as an editor, and it doesn't matter if you're a best-selling or an award-winning author, I think you never gain so much experience that you can do without a very good editorial eye. Lynne is extremely talented and also very modest. She's always joking around and saying that she didn't need to do anything on my book, but that's absolutely not true. Her feedback was so critical to the way it turned out."

"Johnny Kellock Died Today was the book's original title. I hoped people would see the title as deceptive. I've had people say, 'Well, it's a coming of age story, and not so much a mystery,' and that's a fair argument, but does the title misrepresent what's in the book? I love the idea that you can have a title that's part of the narrative, and so you have a claim even before you've read the first sentence of the book, and you spend the entire story waiting for that claim to prove or disprove itself. I thought that would be kind of interesting (and I couldn't think of anything better as a title)."

"The basic premise for Johnny Kellock came from an event in my mother's family. My mom was the youngest member of a large working class family living in the north end of Halifax in the 1950s. She was almost 20 years younger than her oldest sister, and she has nieces and nephews that are just a few years younger than she is. She had a cousin who left without much explanation when he was a young man. I guess he died in the 1980's, and I remember when I was a kid that that's sort of when we found out what happened to him. We received the death certificate, and I think my grandmother, as his next of kin, must have received a few of his belongings, but we never really did know the details of his life. While my mom had very strong memories of him from when she was a child, I didn't go back to my family and find out more. I wanted to explore that idea of 'Why would somebody leave?' through the story."

"And, of course, as with so much fiction, you start off and you 'steal' things from life, but the resemblances become very superficial in time. As a result, the mother in Johnny Kellock no longer looks or sounds like my grandmother, and Rosalie became her own character. Nonetheless, my family on my mom's side still persist in reading the book and going, 'Ok, Young Lil is ....'"

"David Flynn, the Gravedigger boy, is made up. At one point in writing the story, I got very frustrated because I felt like I had a beginning and a middle and an end. I knew what the major episodes were going to be, and I'd written the climax of the story and everything, but I felt like Rosalie was an observer. Everything was happening around her, and she was reacting to it. Actually, I think it's OK to do that, but you don't want that to be the case in every children's book. You want your protagonist to be active. That's just good fiction, but it's also true that children aren't always in control of what's going on around them. However, from a literary standpoint, I wanted this to be more her story than it was, and this boy, David, just appeared and I thought, 'Well, I'll just go with this.' I'm a big believer in just forging ahead and seeing if it works, and the story came together.' I'd written about a character like him before, and I am going to write about a character like him again I'm sure. There was one boy from my childhood that the Gravedigger reminds me of, but he was younger."

"That separateness of schools that's found in Johnny Kellock was very true of what my family's experience was in the north end of Halifax. There really was a Catholic school next to an Anglican school, and they really did hurl taunts at each other across the school yard. One of my aunts said to me that it was great when they were teenagers because you could go to a community dance and there would be a whole bunch of new boys that you could dance with because you went to separate schools."

"When I was writing Johnny Kellock, I thought, 'How can I write about the north end of Halifax without writing about the African Canadians who have been there for hundreds of years.' The reality was that when my mom was a kid, there was a lot of segregation, and unfortunately it's true that she would rarely have seen a black student in the summer time because they lived on different streets in different neighborhoods, and, at least in my family, there was no mingling outside of school. I decided that, to represent it otherwise, would be to rewrite history. I really wrestled with this issue, and I actually wrote scenes with Black Canadian characters, but I ultimately decided that I was forcing them into the story."

As to what's next, Hadley says, "I'm trying to finish the first draft of a new book, but that's very difficult to do while working in the book industry because there's lots of other demands on my time. It has a lot of similar themes to Johnny Kellock but it's all writ a little larger this time. I'm returning to that idea of friends again. I grew up in a village, a very small place. Your after-school friends weren't necessarily your school friends, and your summer friends weren't necessarily your winter friends. It was just that geography brought you together, and your experience of that person would be completely different in a different setting as well. As adults, I think it's very easy to forget that. I remember the relief of going to university and being able to choose my friends. I think I have some stuff I need to get out of my system, and then I hope to go off and write just funny books. I'm going through the highs and lows of the first draft. Some days are wonderful, and I love to be with these characters. I'm hopeful that this will be a better book than the first book. It's important to me to progress, and so perhaps I put too much pressure on myself to try and improve in this next book. As a result, some days I feel good about it, and other days I'm just trying to get it done."

"Four days a week I'm at Lorimer in the afternoons, and then Fridays I flip, and so they get one morning where I'm a little more alert. In theory, I write in the morning, and especially when the light comes up so soon as it does in the summer, sometimes I'm up at 5:30 or 6 o'clock and write before the day gets away on me. That's the only way I know how to do it. If I'm having a really good week, I might go back to writing in the evening, but I never ever count on it. I just don't work that way as I rarely produce my best work in the evening. Sometimes I'll reread what I've written, and then I'll get sucked in. Then I can write a little bit more, or at least I work at a problem, but on typical weekdays and weekends I try to get up and write. It is very hard because the editorial work I do uses the same brain cells as writing, and teaching and correcting assignments do too. So much of writing is evaluating what you've put down on the page. As well, I still write magazine articles. I hope to get to a point in the near future where I can simplify my life a little bit and just focus on writing fiction and editing and do less extra work."

"We're trying to restructure my job at Lorimer now. I've been working with some freelancers for so long, and they're quite good. Jim wants me to work more on development and acquisitions, and so I'm going to be relying more on freelancers to take over projects earlier and to see them through. They will be the editor and have a relationship with the author, and I think that will work very well as the freelancers like working at home. It's lovely to be able to hand over a book and trust that it's going to be alright. Jim would love it if I were to come in full-time, and we talk about it every now and then. I think the experiences I've had recently as a writer and as a teacher too have really been to the benefit of the company. I"m very lucky because, as a teacher, I once again have that nondenominational role, and I can talk to my colleagues and stay in touch with what they're doing and their procedures and practices, and so I learn even as I am preparing to teach my students. Things like that would be hard for me to give up."

"As I said, the magazine writing is my having a little gig on the side just in case everything else falls through. I have a small, but fun, job writing the family listings for Toronto Life magazine every month. I write up all the kids events going on in the city. I have to do a little research, but over time so many of the venues and the arts groups have started coming to me. Like all the writing I've done, whether it's a press release, an article or whatever, this Toronto Life column has actually helped my fiction. By the third time you write about a pirate play and you have a hundred words in which to describe it, you have to have very punchy prose to make it engaging in a small amount of space. It's a real discipline that actually gets more challenging with time. For about eight years from the time I was in London, I had a column with Canadian Family Magazine. I wrote about technology, something about which I knew nothing. Every month I would ask myself a question like, 'What is a cell phone?' or 'How do you get your printer to work?' Then I would go and find out. I still occasionally do an article for Owl, and that's about it these days. It seems though that, no matter what I write, I benefit from it in the long term."

"My practice has been to write directly on the computer, but just recently I've tried to start writing by hand again. I think it's a great way to 'steal' time if you have 10 minutes and a cup of coffee and you're waiting for an appointment or whatever. It's much easier to do that if you write by hand. A couple of timesp;&nb recently I've been in bed and mulling something over and I've written it down by hand. Then, when I've gone to the computer the next day, I've popped off a thousand words because I've managed to 'think' on paper. However, I think it comes much more naturally for me to type because I don't think in a very linear way (or some people might say I have a short attention span). Typing allows me to capture my thoughts as they come out and then to reorganize and reorganize and reorganize."

"If you look at my office at Lorimer, everything is very contained. It's not that there isn't any clutter. It's just contained clutter in that often I just put a certain type of clutter in one pile or preferably in a box or a file, and then I can manage it. It's funny, but that's how I write too. I don't, I can't, I would love to, but I seem quite incapable of writing a story from beginning to end. Writing is often a pleasure, but it's not always. It's work, and sometimes it isn't going very well. The problem with my approach to writing is that, down the road, I'm faced with the question, 'How do I stitch this complex thing together?' which is what I'm trying to do now with the project I'm working on. If you look at the manuscript on my computer, you'll see how I'm trying to arrange my thoughts and the clutter by moving things through different phases and having different files for them. I have a record of everything, but I can't help the fact that I have a very messy mind. Sometimes I'll write a sentence, and, if you were to look over my shoulder, you would see two seemingly disconnected phrases or words and then another sentence. As it comes to me, I have to put it down."

"I do think I owe a lot to my writing group who are my first editors. Kathy Stinson, Paula Wing who's a playwright and Lena Coakley who's published two picture books so far and hopefully a novel soon. I so value the input that they give me, and each brings different strengths to the process. They get their paws on my work as it's developing. In all honesty, I don't think I would have finished the book, and I don't think it would have been the book it turned out to be without their input. Every few weeks, we get together and read our work out loud, a practice which I think is very useful. When you read your work out loud, you handicap your adult reader who is evaluating the work and who can't go back and reread what's been written. It's like tying one of their hands behind their back. If they miss it the first time, they've missed it, and they are confused. Actually, as an editor, I can often recognize when I've received a manuscript from somebody who has a writing group, especially if it's from an emerging author and is very nicely put together. You can tell somebody has already put them through their paces."

"I took Kathy's Stinson's writing course once or twice while I was working at the Children's Book Centre, and I took Peter Carver's once. It was while I was taking Peter's course that I read the first two chapters of Johnny Kellock. This was in 1999 or so, and then I hardly touched the book for the next however many years, but it was because of Peter's class that I actually started putting thoughts on paper for that story. He's been a huge influence on me as editor too, especially his philosophy about what makes a good book and being committed to the quality of the literature and making a work that is accessible and also relatable to a young audience. All of these things are more important than any other consideration, including sales."

With Bobbi Kalman

This article is based on an interview conducted in Toronto, ON, on June 8, 2007 and revised in December, 2007.