Books by Mary Harelkin Bishop.

Mary Harelkin Bishop

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

Although Mary Harelkin Bishop has lived in Canada for most of her life, she was actually born in Hillsdale, Michigan, on April 30, 1958. Her father, a Doukhobor from around Langham, SK, had gone down to the United States looking for work, and there he met his wife. When Mary, the eldest of five children, was nine, her mother was killed by a drunk driver, and Mary's father, lacking any local family support, moved his four daughters and one son back to Canada, first to Ontario for about 18 months and then to Saskatoon, arriving there when Mary was four months shy of turning 12.

Although Mary Harelkin Bishop has lived in Canada for most of her life, she was actually born in Hillsdale, Michigan, on April 30, 1958. Her father, a Doukhobor from around Langham, SK, had gone down to the United States looking for work, and there he met his wife. When Mary, the eldest of five children, was nine, her mother was killed by a drunk driver, and Mary's father, lacking any local family support, moved his four daughters and one son back to Canada, first to Ontario for about 18 months and then to Saskatoon, arriving there when Mary was four months shy of turning 12.

Like so many authors, Mary can trace her interest in becoming a writer back to her childhood. "I've been writing since I was nine-years-old, and I started writing because of all the changes that happened in my life. Because of my mother's death and then the moving, I just didn't feel like I had anything that was mine, and I was dealing with all these feelings of losing a parent and change. At the time, I just started writing journals, poems and short stories." Mary also recalls always being a reader. "The first series that I remember reading was Hugh Lofting's Doctor Doolittle books, and, in my memory, it seems to me that there were probably six or eight of them. I was totally thrilled with them. Ellen MacGregor's Miss Pickerells books were another series that I read, and I also loved fairy tales."

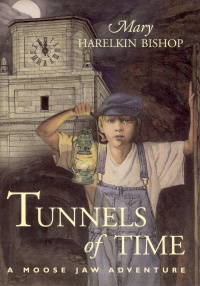

"When I talk to kids in classes, I tell them that I started sending things in to magazines and to book publishers when I was 18. When I turned 24, I hadn't had any success, and so I thought, ‘I must be doing something wrong.' I went to the library and took out books that told me how to submit things properly, and then I went back to work at it. Between the time I was 25 until I was about 39, when I found out that Coteau Books was going to publish Tunnels of Time, I had two poems and one short story published, all in Green's Magazine, a tiny little Regina-based publication. And I was really trying to get published. One manuscript of an adult book, which I still think is a good book, I sent to 50 publishers. I talk to students about the fact that these three published things don't represent a lot of success, and I ask them, ‘What was it that kept me going?' And then I talk about persistence and determination and following our dreams."

From grade six on, Mary took all of her public schooling in Saskatoon. "After high school, I applied to the University of Saskatchewan, and I also applied to Kelsey Institute. Since my family didn't have a lot of money, I decided to go to Kelsey. Because I always knew that I wanted to work with books and with kids, I took the library technician program which, at the time, was only a year long. I was 19 when I graduated, and that fall I got hired on with the Saskatoon Public School Board."

"I worked as a library technician for about 13 years, but people kept saying, ‘You really should do something else.' By this time, I was up at the top of my pay scale, but my decision to change careers wasn't really about the money so much as it was, ‘What else can I do?' The answer was to go to the Faculty of Education at the University of Saskatchewan where I did my B.Ed. One of my fields of specialization within the general elementary program was school librarianship, and the university counted some of the courses from my Kelsey program. As well, I also did a couple of classes in library science in the B.Ed. program."

Following the completion of her B.Ed., Mary returned to work in her former school division, but now she assumed a different role. "I've worked in many schools in Saskatoon as a teacher-librarian. I would always be in two different elementary schools, half-time in each, but this year I'm at Mayfair Community School where I'm not in the library. Instead, I'm doing a special program where I'm called a ‘literacy teacher.' As a result of the Board's looking at the low reading levels in our school division and then deciding to try to do something about it, they hired eight of us as literacy teachers in the community schools. I'm working with students in grades 6-8 who are at least two years below their appropriate reading level. For 90 minutes a day, I work with them in a small group of about 15."

Even though Mary has authored four books about the adventures of a contemporary teenager, Andrea Talbot, and her younger brother, Tony, in the tunnels below Moose Jaw, SK in the 1920's, Mary did not specifically intend to become a children's writer. She says that her various writings have always ranged from things of interest to kindergarten to grade two children right through to adult materials. However, after during a family visit to the tunnels of Moose Jaw, Mary became fascinated by the tunnels and their stories and decided to write about them.

"As happens when a story forms, my mind started asking questions. ‘How did they get lighting down here? Did they carry torches? Did they have lanterns? What did it feel like to be in this closed space, probably in semi-darkness?'"

"They took us around and showed us another little tunnel that they called belly tunnels. These were even smaller, and you would have had to literally crawl though them. They were pretty much dirt whereas the main tunnels were cement or rocks. You couldn't go through the crawl tunnels as they were too dangerous. Naturally, the idea of these crawl tunnels grabbed my attention. As well, there were just so many conflicting stories about these tunnels. Some of the locals were saying, ‘Oh, the tunnels are just gimmick,' while other people were saying, ‘No, I played in them when I was a kid. I know they've been around.'"

"So, I just started asking questions and trying to talk to people. A lot of people weren't very open to talking about them because, to admit you had a tunnel in your business, would be to admit that somebody somewhere along the line in your family was obviously doing something that you didn't want to talk about. When the first book was coming up, Coteau said, ‘We need a map, and the hardest thing that I had to do was to take it out of my brain and try to put it on a map. According to the people I've talked to, the tunnels did actually run from behind the train station all the way up Main Street and then out either side for a few blocks. Basically none of those tunnels is available now."

"My best writing happens when I carry my stories around in my head for a long time, and they just somehow develop that way. I actually carried this idea for Tunnels of Time in my head for about four months, which isn't long time for me, but, by the time that four months was over and I started to write, I just knew what the characters were like."

"Couteau rejected Tunnels of Time the first time I sent it to them, but they did say that it was a good idea and suggested some things I needed to fix. They were encouraging and said, ‘If you fix it up, send it back to us,' and so that's what I did. One of the things they said was that it was too short, and it was. It was only about a hundred pages. Another thing that they didn't like was the way I portrayed Ol' Scarface. I had a little trouble with that aspect because I purposefully left out Andrea's having to think, ‘Was this somebody she could trust?' I thought that his being kind of nice to her and then not nice to her really added stress and interest and conflict in the story. Coteau's point was that, historically, Al Capone was a bad man and that I really needed to paint him black. That was one of the points that the editor and I never agreed on. She always thought I made him too nice, and I always thought I made him so bad that I took away all that stress and tension."

"What happened with Tunnels of Time is that I signed the contract, and then it sat on the shelf because Coteau wanted to bring it out with a nonfiction book about Moose Jaw. They thought that together the two books would do very well. So, while Tunnels of Time was sitting around at Coteau, it was also going around my school in binders because kids wanted to read it. The kids kept coming up and saying, ‘That's so good. Is there going to be a sequel?' And I kept saying, ‘Well, I don't think so,' because I was worried I was a one hit wonder, and I didn't want to write something just because people were saying, ‘Oh you should write something.'

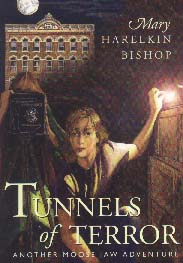

"However, I had ideas for Tunnels of Terror from a newspaper article I had found. Dated February 24, 1924, the article said, ‘Seven constables of the local force facing charges of robbery,' and their names were listed. When I read the article, I thought, ‘That fits. The time is right.' I had that idea, but it just didn't feel like it was enough to carry a whole story. I carried that book in my head for a whole year. I had everything growing, but it just didn't feel like it was enough.‘What else could happen?' I asked myself, but I didn't have any ideas. Then a little girl at one of my schools got sick and went into the hospital really quickly. At the time, I was doing literature circles with her class, and every time I sat down with a group, they would ask, ‘What's wrong with Sarah?' Nobody really knew, and everybody was worried."

"About a week or so later, Sarah came back to school and told everyone she had diabetes. I thought, ‘That's perfect for the story.' I knew Sarah had an older brother, and I began thinking about her family and asking myself questions. ‘Did they just take sugar totally out of their house? How did they deal with snacks? Does her brother not get to have things because Sarah can't?' My first thought was that it would be Andrea who would get diabetes, but then I realized, ‘No, it wouldn't really faze her too much. She could handle that, but Tony would be really very upset, really angry, and really scared.' And so that's how that part came together, and then I knew that it would really carry the story. The other thing about having diabetes in the book is that getting diseases like diabetes does happen to kids, just like it happened to Sarah. I think it's really good for children to read about such things and to realize that not good things can happen to you, but you can still cope with it and find your way around. Like Tony, you can still be angry and upset, but you just somehow hopefully learn how to deal with it. Tony's larger role in Tunnels of Terror just kind of grew from that."

A challenge for authors who write time slip fantasy is finding a believable vehicle for transporting the characters back and forth in time. Not knowing that there would be further tunnel books, in Tunnels of Time Mary had Andrea move into the past when she knocked herself out by bumping into a mirror while hurrying through a tunnel. Although this approach worked well in a one-off situation, Andrea, as a continuing character, would be at risk of serious brain damage if she always had to be rendered unconscious from a blow to the head in order to enter the past. Mary acknowledges that finding a solution to the time switch situation was another thing that held up the writing of Tunnels of Terror. "Once I had the Tony idea, then my question became, ‘How do Andrea and Tony get back into the past? As they're driving to Moose Jaw, are they in a car accident?' My solution, the ‘magic' armoire, is kind of like The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe."

"I did some research on the police corruption because you always want to try and get your facts correct. From the reading I did, it appeared that the police chief was deeply involved, but he never got indicted for anything and managed to keep himself really ‘clean' even though there are lots of instances about money disappearing and then reappearing a couple of days later when somebody would ask, ‘Where's all that money gone?' I was going with the police chief in the original version of the book, but Coteau said, ‘You could get sued for libel because his relatives probably still live around there.' Consequently, the chief became an anonymous sergeant. My inclusion of the police hiding stuff in the tunnels was more speculation but based on stories I heard of the ‘My great-grandfather's best friend's brother said' type of stories. I guess I tend to believe such types of stories."

Observant readers will notice that all of the titles in the "Moose Jaw Adventure series" have an alliterative "T of T" structure. Says Mary, "Originally, I had entitled Tunnels of Time ‘It Happened One Night in Moose Jaw' because the book's action occurs basically, but not quite, in a little more than 24 hours. I gave the manuscript to a group of boys and girls at Brevoort Park School in Saskatoon, and I said to them, ‘It Happened One Night in Moose Jaw' is an OK title, but it's kind of boring. What can you come up with?' They read it and suggested ‘Tunnels of Time.' Because publishers have a say in titles, Coteau called saying they wanted to name it ‘Running Out of Time.' I replied, ‘I don't really like it. It doesn't hug me.' And just as I was getting off the phone, I said, ‘Here's a great title - ‘Tunnels of Time.' ‘No' was the reply, but a couple of days later my editor phoned me back and said, ‘That title stuck in my mind.' That's what you want a title to do, and they decided to go with Tunnels of Time. I was really happy for my boys and girls.

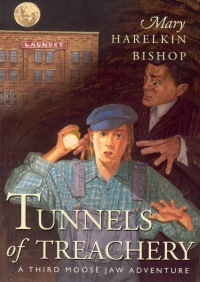

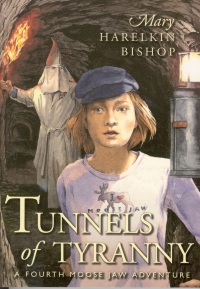

"With Tunnels of Terror, the publisher came with a contract and five titles and asked me which one I liked. I selected the one with the alliteration. As I recall, Coteau pretty much let me name Tunnels of Treachery, but Tunnels of Tyranny was interesting because I wanted to call it "Tunnels of Trepidation." Not only would the alliteration be maintained, but (and this is silly and it's just my kind of thing) the word after the "Tunnels of" would continue to increase by one syllable. "Whose going to know what trepidation means?' asked the publisher who then came back with, ‘What about tragedy?' ‘That's too black,' I replied. ‘Then, what about truth?' they asked. ‘That's a little bit cliche,' I responded. "Torment, tumult?' they suggested before, ‘What about tyranny?' I said, ‘Well, tyranny fits the theme of the book,' but, as I've found, you should try to explain tyranny to grade five students. It's a lot easier to explain trepidation to them. However, it is a great title and works very well."

As Mary was writing Tunnels of Terror, she had considered that Tony might find something in the tunnels related to Chinese immigrants. "After I did some research, I decided that idea would be a book on its own. I went back and read about the national railway, and I tried to read it more from the Chinese perspective. There's at least one Chinese man buried for every mile of track across Canada. There's also the whole head tax thing which started off at $50.00 and was continually raised until it reached $500.00. For a man to bring his family over, he had to have the head tax available for each of his family members when they got off the boat. The Chinese who immigrated were restricted to just four types of jobs. I also read a book from the perspective of Chinese women, just little vignettes, of their lives or their grandmothers. I thought, ‘In Canada, we don't talk a lot about our prejudice and our discrimination towards people," and so Tunnels of Treachery came about because I thought this aspect of Canadian history would make a really interesting story."

Although the broad strokes of the history behind Tunnels of Treachery are true, Mary acknowledges that the story, itself, is not based on any real happenings. She explains the problem she encountered when she tried to do primary research about the Chinese connection to the tunnels. "I work with a couple of teachers who are Chinese-Canadian, and what they basically said to me was, ‘Write what you want because the Chinese people will never agree or disagree with you. They will never talk about it.' One woman even told me, ‘I don't even know how old my parents are because they are very private. To admit that you lived in the tunnels would be very embarrassing to them. Even if my grandparents had lived in the tunnels, I would never know because they would not have talked about it. As well, you have two problems right off the bat. Firstly, you don't speak the language, and so right then they wouldn't trust you. And you're not Asian; that's another problem.'"

Tunnels of Tyranny, the most recent book in the series, also has its roots in a newspaper article, this one dated June 8, 1927, that spoke to a Ku Klux Klan rally in Moose Jaw. "I read two different accounts. One said 6,000 people attended while the other put the numbers at 8,000 people in attendance. The article talked about special trains that brought people from all ever Saskatchewan but, mainly from Regina. When I read that article, I was really surprised and shocked because I didn't realize that the Ku Klux Klan was (a) in Canada and (b) as big as the article was talking about. I thought, ‘There's another instance of "Whoever talks about that?"' I guess, because I work in a school culture where we promote peace and multiculturalism and acceptance of other cultures and here, with the Klan, we have a situation in which somebody would look at you and decide just by the colour of your skin that they didn't like you, made me think, ‘Kids need to know that that was going on and how terrible that is.' I started the book off by having Andrea go to that rally and just be horrified by everything that was happening. The whole ghost thing in the book comes about because, when I look at the costumed Klansmen in pictures, they are very scary looking."

The ending of Tunnels of Tyranny sees the death of Andrea's and Tony's grandfather, Grampa Vance, and his death suggests that the fourth book could be the terminal novel in the series. Says Mary, "There's one more coming, and its action is going to occur a few months after Tyranny. I'm 90% sure that this book, whose working title is simply ‘Tunnels Five,' will be the end of the Tunnel series. In this one, Vance gets kidnapped by his original dad, a hood with the whole Capone organization, and he takes Vance down to Chicago to be part of the group. The timing is 1929 and the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre. Andrea and Tony have to go to Chicago to save Vance from being a part of mass killing in which Vance could have been one the people dressed up in the police uniforms and doing the killing. I've just done the first rough draft of that book, and, of course, I need to lots of editing. I don't know why I've got this thing about Capone. I've done a lot of reading on him, and he was really an interesting man actually, but he was definitely a criminal who would kill you in the blink of an eye. To some people though, he was the nicest, most generous man who gave lots of money away, but you just could never trust him."

When Tunnels of Time first appeared, the Moose Jaw tunnels really weren't too well known in other parts of Saskatchewan. However, because of the book and its sequels, the tunnels now get many tours from the province's schools, and a Moose Jaw M.L.A. even rose in the provincial legislature to acknowledge the impact that Mary had in publicizing what he called "One of the best and most interesting vacation spots in this province." Jokingly, Mary suggests that her contributions to publicizing Moose Jaw could be simply recognized by putting her name on one of the rooms in the spa, "a room that I could use every time I went there."

Being a mother and a full-time teacher meant that Mary had to find time to write. "When my kids were little, I would get up at 5:30 or 6 o'clock in the morning and write. I still do that once in a while. I would also write late at night. Now that my son, who's in his twenties, no longer lives at home, and my 19-year-old daughter is out a lot, I can write after work. If I'm working on something, I make use of the summer holidays. During the school year, I can do the couple of hours a day, but, all of a sudden, I'll get to a point where I have to get this done and I have to get it out of my head. That's what happened with the fifth tunnel book. I pretty much took a whole weekend where all I did was basically get it out of my head."

Asked to talk about her approach to writing, Mary explains that "I carry my stories around in my head for a long time, and what I do before I actually write it is plot it out. I have to know exactly how it's going to start right down pretty much to the very first words that are going to come out of my mouth, and how it's going to end. I like to know down to the last scene, sometimes down to the last paragraph, how it's going to end. In the middle, I have ideas where I want it to go, but I don't set that in stone so much because sometimes when you're working your way through something, it'll just kind of take off and you say, ‘Yah, that works.' So I don't pin the middle down a lot, but I do have an idea of where I want it to go. An example of where the middle changed occurred in Tunnels of Terror where Tony and Beanie are standing in the tunnels, and, for me, it was ‘Now what?' I kind of had writer's block, something I don't get a lot because I know generally what's going to happen. All of a sudden, Beanie hears a sound, and then that whole part about Andrea's being kidnapped happened. I hadn't planned that, but I let it go because I thought it was great. I think that's what makes really good characters, too, if you can really put a life around them. It's like they're my relatives. They live in my brain."

"I think my approach to revising is actually changing. With the first four books, I wrote them and then I started doing all the editing and revising. With this fifth book, the one I'm working on now, I didn't just write it to get it out and then do the revising. I've been kind of revising it as I go along, and that's different for me. It feels a little uncomfortable, and yet it feels good, so I don't know. We'll see what happens."

Not initially intending to write a series, Mary found that authoring one brought demands beyond those connected with writing just an individual book. "The third one, Tunnels of Treachery was the hardest. How do you make it exciting and interesting and different and feel dangerous when the reader and the character had been there already. That was one where I started several times. Even though I had the whole story in my head, I still didn't have the beginning. I thought I had the beginning the way I wanted, and I started writing it, but I didn't like it. Thankfully, it finally came together."

"Another part of writing books in a series is being factually consistent between books. Kids can tell me things about my books that I don't even recall. I've been trusting my memory, but that's not good. That thing called writing in the moment where you just make it up is really bad. I need to go back and check on physical details. Another challenge is that I don't want my characters to see themselves in the past. For example, I don't want Grandpa Vance to come and see himself, and so I'm really careful not to go anywhere near that kind of thing."

Tunnels of Tyranny closes with the opening page from Grampa Vance's journal and writing notebook in which he sets out his thoughts on writing. Mary acknowledges that Grampa's words are really her statement about writing and that it was prompted by her having read Jane Yolen's collection of essays, Touch Magic. "The book is Yolen's statement about the importance of fantasy, and she says that writers, even though they probably don't realize it, or even want to admit it that much, are in everything that they write. I knew that to some extent, but once she said that I started thinking, ‘Where am I in here? Which part is me in all those?' Tyranny is definitely me."

To the observation that her novels, which range between 238 and 300 pages, are longer than the average middle years book, Mary comments, "I don't think I'm a short story writer. I need a lot of room to say what I need to say and to develop my characters. I have trouble with a lot of young adult fiction that's out there because I think it's trite. I think there isn't a message. I don't like it when authors are writing down to kids. They're not bringing the readers up to a higher standard, which is what literature should do. To write down to where they're at doesn't help kids expand their minds nor does it show them the wonderful world of literature that's out there. Literature needs to show kids that they what they can hopefully aspire to and grow into, so that they are the ones who are going to the public library and using the bookstores. If you're writing the other kind of stuff, basically you're writing what kids see on TV."

"I do a lot of writers workshops with kids. I've worked with students from about grade three all the way up to grade 12. I've found that a lot of kids are fabulous writers, and so I just talk about six or eight steps to writing, such as, first of all, keeping an idea journal, then how to start to write, and how to make your characters come to life via colorful, descriptive things." One of the things Mary shares with classes is her own love of language. "I love playing with words. It's an interesting thing because I'll be sitting down working on something, a manuscript, and then something funny will happen at school or will happen to a friend, and I will just write a poem. That's ‘recess' for me, just playing with the words, especially rhyming poetry because that restricts you because you have to be really creative with the words you use."

"When I go out and do my author thing, just talking to classes, I tend to talk about the types of things I'm talking about in this interview, a bit about my life history and being determined and following your goals and how everybody has gifts. You just have to figure out what your gift is. I try to help them figure out what their gifts are."

Although reviewers tend to characterize the tunnel books as being "time travel adventures" or time slip fantasies, Mary says, "I think time travel is a fascinating way to look at history, and I don't consider my books fantasy. I consider them historical fiction using a method to get back to that time period. I actually thought about having Andrea just be a 1920's character, but I think that the books are a lot more interesting because of the fact that a modern kid goes back in time and can stand there and say things like, ‘Look at all these cool cars.' If Andrea had been born in that time, she would have been used to the things around her, like the cars, and they wouldn't have the same effect."

Looking at what may be next, Mary says, "I have lots of ideas. I have a fantasy that's really playing around in my head. I hope to have time to write it soon."

This article is based on an interview conducted in Winnipeg, May 17, 2005, and updated and revised January, 2006.