Books by Matt Beam:

Visit Matt Beam’s website at www.mattbeam.com

Matt Beam

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

Matt Beam was born January 11, 1970, in Toronto, ON, and in his youth, he had no idea that he would one day be a writer. “I mostly wanted to be a sports figure. I was a big tennis player, but I also played baseball and hockey and was a runner. One day I’d be Börje Salming, and the next I was Bjorn Börg. I even had a shirt that said ‘Bjorn Beam’ on it. In high school, things switched for me from sports to social life, much like with Darcy in Getting To First Base with Danalda Chase. I played basketball all the way through high school and ran track my first couple of years. Whereas I would say from grades seven to grade 9, it was sports, sports, sports, from grade 10 to grade 13, it was girls and going to parties, that kind of stuff.”

Matt Beam was born January 11, 1970, in Toronto, ON, and in his youth, he had no idea that he would one day be a writer. “I mostly wanted to be a sports figure. I was a big tennis player, but I also played baseball and hockey and was a runner. One day I’d be Börje Salming, and the next I was Bjorn Börg. I even had a shirt that said ‘Bjorn Beam’ on it. In high school, things switched for me from sports to social life, much like with Darcy in Getting To First Base with Danalda Chase. I played basketball all the way through high school and ran track my first couple of years. Whereas I would say from grades seven to grade 9, it was sports, sports, sports, from grade 10 to grade 13, it was girls and going to parties, that kind of stuff.”

But Matt says it was also “around high school when I did start saying that I wanted to be an author, but I didn’t do anything about it for a long, long time.” Matt did, however, take two creative writing courses while in high school. “I think it was grade 11 that I took my first one – ‘Writers’ Craft’ it was called - and then I took another similar class in grade 13. I believe they were option courses, and perhaps at the time I perceived them as being easier, but this didn’t end up being the case. Those courses were just as hard as anything else I did in high school, and I remember really enjoying the work. Even then, at 17 years of age, it was not clear to anyone, including me, that I would become an author.”

Matt remembers several of the stories he wrote at that time. “I recall trying to do way too much. Yeah, it was in that grade 11 Writer’s Craft class that I thought I might actually write a novel, the diary of a Russian soldier in World War I. And then I thought of the mountain of research I would have to do and decided to aim for something a little smaller.” His chosen subject matter wasn’t surprising given the reading he was doing at the time. “It was in high school that I fell in love with reading, especially spy and detective books by writers like Robert Ludlum, Leon Uris, and Lawrence Saunders. I became a sudden bookworm – I was the kid in class with a book hidden inside his textbook.”

But Matt kept the goal of becoming an author in the back of his mind. “I guess I was always unrealistically ambitious in that regard. Even though I wasn’t writing much at all, I began to say aloud, ‘I’m going to be a writer one day – once I sit down and start, I won’t be able to stop,’ and yet while I was saying this, I don’t know if I actually believed myself. I don’t think anyone else did either, and so the ‘being an author’ thing didn’t affect any of my decisions at university.” Because Matt comes from a family of academics, there was a push-pull dynamic going on with his university decisions. Now retired, his mom was an English professor at the University of Toronto, his dad, also retired, was a professor of income tax at Waterloo, and his sister now is a professor of history. “But,” Matt says, “my sister was still a grad student when I was at Dalhousie. I didn’t take a single English course, not one, being the rebellious son, I guess, and I also ended up dropping accounting in grade 13. But I did end up doing a BA in history because that’s what my big sister had done.”

Questioned about what he had planned to do with his history degree, Matt responds, “I had no idea. I wasn’t the most focused of students. I was Mr. B minus, and I was going through the motions a bit. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life, and I’m not one who thinks things through beforehand, and so I was just ‘living,’ or, as I like to say now, ‘researching.’ I don’t know how much of this comes through in my books, but I was the stereotypical athletic son who didn’t do so well in school. I didn’t do poorly, but I basically grew up thinking I wasn’t the intellectual one and certainly not the one to become the writer. It took until I was about 28 for that to change.”

Hints of the writer-to-be, however, did come through in Matt’s university papers. “I just loved making things up. As a history student at Dalhousie, the theses of my essays were just out of this world. I was always fictionalizing things and wanting more from my essay than was possible. I wanted there to be some grand scheme, but I could never prove it, hence the B minuses. I really regret my university years because I didn’t put in a lot of effort until late in the degree. In retrospect, I wish I had gone to Whistler for a couple of years, worked at a job and had all that fun. And then, having been in the real world and seeing what it was like to work for a living, I could have then focused more intensely on university and what it had to offer.”

As his university days came to a close, Matt was preparing to see some of the world. “In my last year at Dalhousie, I took an introductory Spanish course where you learn the basics – the verb tenses, some grammar, some vocabulary, that sort of thing. My mother had gone to Guatemala a year earlier and said that she’d had a great time there, but that I would absolutely love it. So I went. I studied Spanish intensively for a couple of months in a tiny school in a town called Quezaltenango, which is also called Xela, the Mayan name. It was one-on-one conversation classes, five hours a day. The school was this beehive of students and teachers, speaking one-on-one in little cubicles. I lived with a local family, and then I did a little bit of volunteering at a school in Antigua, Guatemala, before doing some traveling. That was where my wanderlust began.”

“When I came back to Canada in 1994, I soon moved to Vancouver and got my first teaching job at an ESL school. I loved it, and I thought I’d fallen in love with teaching, but what I’d really fallen in love with was teaching highly motivated, seriously respectful 25-year-old Japanese students how to speak English. I got the job in just three minutes, on little more than my smile. There was no curriculum, nothing, and I had to figure it out on my own, which was wonderful. That experience was the beginning of my love affair with English, learning about the language and how complex it is, and what I didn’t know and what I still can’t exactly explain about how it works.”

“It was actually in my earlier Guatemalan experience that I started to look at language in a different way. It was interesting. In the second language context, I was the student first and then the teacher. When I was the student, I was quite stubborn, and so I would speak Spanish as if I were speaking English, grammatically that is. I wouldn’t believe the teachers that this was not the way the language was spoken. Then, a year later when I was in Vancouver and teaching ESL, I was very frustrated by students who would stick to the grammar and structure of their own language. For example, my Japanese students would omit the article before a noun. It was always, ‘I see dog,’ not ‘I see a dog.’ It killed me.’ I wish I’d taught English before I’d studied Spanish because I think I could have learned that much more.”

“After about a year and a half in Vancouver, I returned to Toronto and started to cast about. I did odd jobs and actually wrote my first unsolicited – and still unread – article about a rock climbing experience I’d had. It was exhilarating, but I still hadn’t seen the light, as it were. So I finally asked myself, ‘What am I going to do with my life?’ I wanted to continue to travel, and I’d heard that you could go to Australia and do your teacher’s degree, and so I did just that in 1996.”

Following the completion of his teacher education program at the University of Western Sydney, which included a once-in-a-lifetime, four-week practicum in Nandi, Fiji, Matt took his newly minted Master’s of Teaching credential and taught grade 8 in New Zealand. And it was there, through an assignment Matt created for his students in South Auckland, that the idea of becoming an author returned.

“It was an editing assignment, and I needed two pages of fiction. All of the grade eights in the school were to read the story and then edit it. I was to create the errors in the text, and the students had to find them -- the spelling mistakes, the missed commas, that sort of thing. When I couldn’t find a two-page story, I thought, ‘Hey, I’ll write one.’ I went home and wrote for five hours, and the story that resulted was called ‘Frankie and Mata.’ Mata is a Maori name, and the story was about two best friends, a boy and a girl, causing a little bit of trouble in class. I just fell in love with the process, and the time flew by. At that point, I had lost control of my class, so I definitely wasn’t enjoying the teaching job. The contrast was amazing.”

“That experience was really it for me. I had finally ‘sat down,’ and I didn’t want to stop. I knew that we, my girlfriend and I, weren’t going to stay in New Zealand forever, and we eventually decided that we were going to return home at the end of the year. At that point, I pretty much felt, ‘Well, I have my teaching degree, so I can be a teacher at some point, but now is my chance. I’m 28; I might as well go for it. I don’t know anything about writing novels, but I’m going to start and try to work it out.”

“I began by writing some adult short stories, but I was completely daunted by the audience. I got very wordy and complex and didn’t end up telling a story straight. When I started to write for younger people, I felt more comfortable because I realized that I had just to make it simpler. As is often the case, whether you’re writing essays or writing fiction, you have to start simply. And even if you start simply, it will inevitably become complex if you want it to. The first novel just came to me. In less than six months, I had written my first young adult book, Can You Spell Revolution? ,which finally appeared in the fall of 2006.”

“Negotiating the publishing industry was a long strange process for me,” Matt admits. “I had no idea how it all worked. The book was originally called ‘In Clouds,’ and I sent it into several publishers, including Stoddart and Farrar, Straus, & Giroux in New York. Actually, I sent them both six chapters. Two months later, they both replied, saying, ‘Send the rest.’ FSG eventually rejected the novel, but they were nice about it, saying they were sorry, the book wasn’t right for them, but that they were sure another publisher would want it. Some six months later, Stoddart finally got back to me saying, ‘We like it, but this is what we want to see you do with it.’ It was my first editorial letter.”

“I responded to the letter in a month and sent the revised manuscript back. I didn’t hear from them for another eight months. I was going crazy. The sound of the mail dropping to the floor in our apartment hallway began to have a Pavlovian effect – my heart would immediately start racing. Finally after all those months, I got a call. Actually it was a voicemail because my girlfriend had ordered me to go for a walk so as to stop me from pacing inside the house. I still have the voice mail recording of them accepting the novel, but then, within a month, Stoddart went bankrupt. From there, the manuscript went through an Odyssey-like experience. There are two Toronto Star articles on my website which explain the whole six-year ordeal. As a result of all the delays, my first three books, in terms of publication, got all mixed up. Getting to First Base with Danalda Chase, the first of one to actually appear in print, is really the third book that I wrote.”

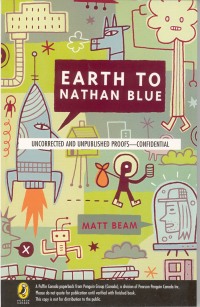

“The second written book, Earth to Nathan Blue, is now the third to appear, and that story has gone through a lot of changes. I was still learning how to write a novel at the time, and I took on a lot with this particular story. It was much much denser in the original version. Nathan’s language was even more playful and complex, and each of the TV products and jingles had different fonts. I acknowledge the many changes in the manuscript at the back of the book where you will find I’ve thanked Kwilcam Zizinger and Esoh Onerom, former names of the protagonist, Nathan Blue. Poor Kwilcam just had to go.”

“But I had created quite a complex world, and, as the story developed, it became more and more tangled. Untangling it, or as my agent called it, ‘throwing it on the ground and cracking it open,’ was a painful but necessary thing to do. It was a lot of work. My real novel-writing education has been in editing these first three books. I’ve learned a lot in the last couple of years - the professional editing process, how to structure a narrative, the importance of character, etc.” Matt acknowledges that he had some “great fun creating the Plutonian words in Earth to Nathan Blue,” and that “at a certain point in the process, the book simply became a book that I could read and enjoy. Actually, with all my novels, I quickly feel distanced enough that I can laugh and cry with the characters as I read through.”

In Earth to Nathan Blue, Matt does some subtle things towards the end of the book to signal the gradual changes that are occurring in Nathan as he moves beyond his imaginative world. One such example is Nathan’s not always using “Imposter” to describe his mother’s boyfriend. Says Matt, “Every single usage of Imposter was consciously considered. I had a copy editor constantly querying, ‘Are you sure you want “imposter” there?’ There’s a moment where Sharon, the young girl he has met at school, has asked Nathan to stop use his whacky language for a while, and for about five pages Nathan becomes a regular kid. There’s a point though that Nathan becomes scared and angry, and so he reverts back to his protected, imaginative world and language.”

“I think my books must obviously be about something that I experienced when I was a kid. For example, with Earth to Nathan Blue, I didn’t or couldn’t express myself the way Nathan does when his parents split up. I was five when my parents broke up, and I ended up living with my mom and my stepfather, and so maybe writing for me is trying to go back and alter a few things and then seeing what might have happened. It was not at all conscious though. I’m always surprised when I look back at novel and think, “Hmm... that situation looks very familiar.”

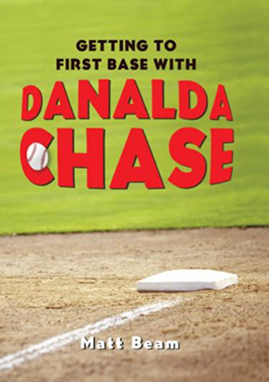

“With Getting to First Base, it’s clear where the subject matter came from. I loved baseball. It’s such a fastidious sport, and the stats are so important. As a kid, I compared myself to the Blue Jays players. George Bell is batting .334, and I’m batting .567. Not bad! I was a pitcher and had every pitch you could imagine - a fastball, a curve, a knuckle ball, a knuckle curve, and a change-up. My coach was not happy about all my pitches. He’d step out of the dugout and say, ‘Beam! Just throw a fastball.”

“Getting to First Base is coming out in the U.S. with Dutton. I was asked to make many changes to the novel, and it is definitely a different book. In the American version, everything takes place in six months as opposed to a full year, spring to spring, and so we start the story with Darcy, Dwight and Ralph sitting by the side of the baseball diamond looking at Danalda in the fall of grade 7, instead of the spring of grade 6. Anything that happened in that six-month time period, I flipped over, if it worked, but not everything did, and so there were several significant changes that had to be made.”

“I was working with Dutton first, and then HarperCollins Canada, and then Dutton again. By the end of it, I’d probably done nine to 10 fairly substantive edits. There was one small but significant change for the Americans -- No ‘goddamned’ from Grandpa. I ended up replacing ‘goddamned’ with ‘gall-stoned.’ Grandpa Spillman is the one who says it most of the time, so I guess it makes some sense. I learned a lot about compromise in that edit. But I don’t feel as attached as perhaps some writers do to their manuscripts. For me, the love affair is the initial writing, and then at a certain point, it’s like a child. Even though I love it, it is separate from me. At that point, when I hear a suggestion and it’s good, I’ll do it. That said, I think I’m getting better at standing up for myself and my work, and so I’ll likely be a bit more stubborn next time around.”

Asked about his approach to writing, Matt says, “One draft of a novel that I wrote recently was very tightly crafted. I knew what I was doing almost all the way along. That’s not how I usually approach my writing. Often I have little idea what is going to happen next. Actually that’s not true. I tend to know the hook, the beginning of a story, and I have some idea how it is going to end. In my presentation to students, I’ve introduced this concept as a metaphor, with the help a PowerPoint presentation. I show a trailhead with a sign that I’ve manipulated in Photoshop to say, ‘Matt Beam Trail.’ I say to the students, ‘When you start a hike, you’re at the head of the trail, and you know where you are beginning. This is like me and my writing. I always know the beginning of my story. I have a sense of who this character is and what his or her purpose is.’ Then, when you are at the trailhead, you take a couple of steps back, and you point at the mountain peak -- I show a prepossessing mountain peak image -- and say, ‘That’s where I’m heading. That’s the end of my story.’ So I always know my beginning and my end, but in between, I have no idea. Now, of course, there are markers along a hiking trail. Not on my writing trail. It’s lots of bushwhacking and discovery. I often take a wrong turn and find I have to head back in the direction of my ultimate goal.”

“I have a few confidantes that I will show my work to, but they are not writers, just very good readers. I think I have this tendency to not want to be influenced by anybody, so this is hard. I’m very stubborn. I read a lot of nonfiction, but I have trouble reading fiction of any sort because I don’t want to be influenced. I’m sure there is a lot I could learn from other writers, but I just don’t want to lose my almost naïve approach to a narrative. Having done all these edits, I now understand the craft much better, and I now find I’m in a bit of a battle between craft and art. I know more of what I’m doing, and I have more skill as an author, but I believe part of the reason why I’ve had success so far is that I didn’t have anything holding me back. I just went with what I wanted to write, second by second.”

“For instance, in the original version of Getting to First Base With Danalda Chase, there were probably double the amount of characters, and as you would go along the trail of the narrative, every single character had stats. And I don’t just mean secondary characters - we’re talking tertiary characters from the fringes of the story. I was completely free in my writing and didn’t feel like asking myself, ‘Is this character really going to count?’ I’m happy the book was edited because it became much tighter and readable, but the heart of the story comes from this freedom I experienced in my first draft. That freedom causes all kinds of problems, too, but it’s the price I have to pay. In truth, I’ve started to ask myself the same types of tough questions asked by my editors, but at an earlier stage. As I said, it’s been a bit of a battle in my head¼ Welcome to writing.”

Matt had studied to be a primary school teacher (K-6), but he ended up teaching grade 8 and so, in part, that experience influenced the ages of his protagonists. “I started there because I was teaching that age. I came back from New Zealand with all of these students’ voices in my head. When you read Can You Spell Revolution?, you quickly see that it’s very much about school life, and I think it wouldn’t be hard to guess that I was once a teacher. I had a very intense relationship with teaching, and it was almost addictive in a way. And I wasn’t sure if I wanted to sign myself up for a life of such intensity. What a tough job.”

“In the same way that writing is obsessive and endless, as a teacher, there is a mountain of work to do, and you can never be good enough. With a class of 34 kids, there’s no stopping – I worked so hard. I didn’t have all the skills or experience yet, and so it was a real challenge. School in New Zealand was also a bit different. The kids all wore uniforms, and everything was lineups and protocol. I often found that I was ‘with’ the kids. They would say, ‘This sucks!’ and I’d be like, ‘Sorry. Yah, it does.’ A lot of what Can You Spell Revolution? is about is power, and who has it and how they wield it, in the school context, inside and outside of the classroom. The questions my grade eights often asked me began with the word ‘Why’ – as in, ‘Why do I have to do any of this stuff?’ And I didn’t always have the answer. By the end of it, I was just responding with a conversation-ending, ‘Because!’ I became quite a tyrant as a teacher. I started to not like myself.”

Matt now has to deal the realities of the writing life. “I was excited about my first book coming out, but people were saying, ‘You can’t make a living at this.’ I’m not sure I believed them, but I do now. Life is the best teacher, and so is an empty wallet. I used to write journalistically - sports, travel, popular culture, and my pieces have been in The National Post, Toronto Life and the Toronto Star, but I slowed down with journalism about a year and a half ago. The pitching is so much work, and I didn’t feel like I could do both the fiction writing and journalistic writing for the number hours a day I could work. Now I mostly do research for magazines. It actually pays better than writing the articles, or at least it’s more consistent. I’m also thinking about getting back into ESL teaching and tutoring.” Matt has the time for other work because his fiction work only takes a portion of his day. “I write for about two to two and a half hours a day, and half of that is editing what I wrote the days before. When I am really going at a clip, I can do three to four pages a day, five days a week. At that rate, in three months I can pump out a first draft.”

“I’d also love to teach an editing class at some point, because I feel that that’s what I like about writing. Editing turns a stack of pages into a manuscript, a manuscript into a novel. I do like the slapping down of the ‘raw materials,’ but I love coming back to something I’ve already written and just making it better. About two or three years ago, I interviewed a childhood favourite of mine, Gordon Korman, and he said he wrote longhand and that, for him, when a sentence was down on the page, it was pretty much done. It’s completely the opposite for me. I’ll probably go over the same sentence 25 times and then throw on another 10 more edits when the pros get in there. I’m just constantly preening -- I love that process. I think the problem some hopeful writers have is that they feel like they have to write it perfectly on the first go ... or that’s all they actually want to do. My argument is, ‘If you don’t like editing, then you don’t like writing.’ Having brilliant ideas is one thing, another is getting into the trenches and working.”

Matt describes his ideas for books as coming as answers to questions, and the question is usually a "What if...” question. “It’s basically creating a scenario. So, for example, ‘What if a boy who loves baseball really doesn’t know what 'getting to first base’ means and suddenly wants to get there?’ I actually have more ideas than I’ll ever be able to write.” Many of his ideas come when he is walking, whether it’s in the city or the mountains. “If I go on a hike, I won’t see a thing around me, whereas my partner’s the exact opposite. She sees the world in its finest details. She’s taught me how to look around which is nice, but, on my own, my tendency is just to think things through. Recently I went to Spain and had jet lag. I passed out at five p.m. and woke up at 11 p.m., and then I was up for the rest of the night. By the time the sun came up, I had three novel ideas, although I don’t know if they’ll ever come to fruition.”

Asked how he selects one idea around which to build a novel from all the ideas he has, Matt replies, “I don’t know. I guess it just has to last. With ‘In Clouds,’ (the original name of Can You Spell Revolution?) long after I had written a first draft, I was cleaning out some old files on my computer, and I found a small Word file which contained just one small paragraph. I guess I had written this paragraph about a month and a half before I actually started writing ‘In Clouds.’ It was the beginning of a novel, and in it, there was a character who was the doppelganger of Clouds McFadden from ‘In Clouds.’ Some small details were different, but it was basically the same guy. So, a character will hit me, or perhaps I just have to ‘see’ them and believe that they’re ‘there,’ that they actually exist in some way. And then, once I’ve assembled a cast of characters in a story, it feels like the rest is almost determined. One person says one thing, another responds, and you’re off to the races. Although there are definitely ideas which never make it onto the playing field.”

“Another writer recently said to me that he can’t start writing until he has the character’s voice. I don’t know if that’s exactly the same for me, but I guess I have to feel the character in a certain way. Actually, all the books I’ve written so far have been in the first person. There’s a reason for that, I think. When I was about eight, I was just getting into chapter books and I read my first first-person book. After reading the first page, I fled down the stairs in tears. I found my mom and demanded to know who this ‘I’ in the story was. She tried to explain, but I insisted, ‘I am I. I am I!’ I didn’t get it, and I felt like my young, self-centred world had been turned upside down. And now ... I write first person books. I am ‘I’. I’ve had a little trouble writing in the third person. I’m not saying I won’t ever do it, but I somehow don’t believe it. It’s almost the reverse from how I felt when I was a child. I try to write in the third person and think, ‘Who is this telling the story?’ I seem to viscerally ‘get’ the first person, a truly subjective perspective.”

Asked about what to expect from him in future, Matt says, “I wouldn’t say that I am a purely comic writer, but I’ve been thinking a lot about humour’s place in fiction. I think it can be very powerful. You can get to a lot of difficult places with it. I could also get a bit darker in my work. I definitely have ideas important to me that are perhaps for an older audience. I have a couple of books on the go. I’ve written a draft where the protagonist is a little bit younger, and one where the protagonist is, I think, at least a year older, in grade 9. I have more ideas than I know what to do with, so who knows what the next thing will be.”

In addition to Matt’s being a writer and a teacher, he also is a photographer, shooting what he calls “abstract colour photography. I’ve been doing it for about five or six years. My recent show is called ‘citypaint.’ Five years ago, the City of Toronto used to spray just orange paint to mark their activities for their underground water and pipe systems. Now, for whatever reason, they’re using every colour in the neon palette, and so my show consists of various images displaying these odd markings in various colours. Before this show, I was doing something even more abstract and macro, which means really close-up. I often compare my work to the close-up photos at the back of Owl magazine where you had to guess what it was in the image.”

Matt began a certificate program in photography at Ryerson, but says, “At this point, it’s mostly a hobby because, when I started doing it, I was younger and I was still asking myself, ‘What am I going to be?’ I finally decided I wanted to be a writer. Hanging around with other photographers, I realized how much passion they had for what they were doing. At the end of the day, you have to choose your battle, and mine is with the keyboard.”

This article is based on an interview conducted in Toronto, ON, on April 24, 2006, and revised November, 2006.