Rosalind Allchin

Profile by Dave Jenkinson.

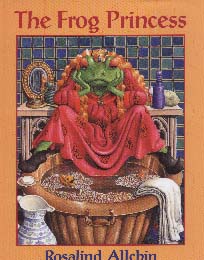

The creator of The Frog Princess, a delightful fractured fairy tale, Rosalind Allchin describes herself thus: "I think I'm an illustrator who writes stories. I start off with some kind of visual image, probably of a character. Although I've never had any formal art training, I've always been interested in the visual arts. When I was in my teens, we used to go family camping in Europe, and visiting the art galleries in Italy was a wonderful introduction. However it's only relatively recently that I've taken up a brush myself."

The creator of The Frog Princess, a delightful fractured fairy tale, Rosalind Allchin describes herself thus: "I think I'm an illustrator who writes stories. I start off with some kind of visual image, probably of a character. Although I've never had any formal art training, I've always been interested in the visual arts. When I was in my teens, we used to go family camping in Europe, and visiting the art galleries in Italy was a wonderful introduction. However it's only relatively recently that I've taken up a brush myself."

Although presently a resident of Ottawa, Ontario, Rosalind was born in West Sussex on the south coast of England on March 26, 1949, the second of four children and the only girl. "We all went to the local primary (elementary) school, and those years I remember as a lovely period in my life, full of painting and reading stories. However at eleven all that changed. In England at that time, secondary education was a two tiered structure, and if you passed the national exam and went to a grammar school as I did, you followed a very rigid curriculum of academic subjects. Art was nowhere to be seen."

"In my final two years at school, I specialized in History, English and German, and after a year spent working London, I went to Manchester University to study sociology. In those days, nobody paid school fees, and the majority of students also got grants covering living expenses. We didn't know it at the time, but we were so lucky. Very few ended up with the vast debts of today."

"After graduating, I really didn't know what I wanted to do. Ironically, the path I eventually took, teaching, I didn't even consider. Both my parents were teachers, and rejection of the well-meaning assumption of adults that I would follow in this tradition was firmly ingrained. It was only after working for a few years as a social worker and having a temporary placement in a school for disabled children that I realized that teaching was what I wanted to do. And after a year's training in London, I was a primary school teacher on and off for the next 20 years. Teaching was very different then. It was before Margaret Thatcher and soon after the Plowden Report which opened up education and which, really for the first time in a large scale way, took where the child was as the starting point rather than imposing ideas downward. There was also money going into education."

"I taught in a Church of England school in Paddington in London. It was a small school in an interestingly mixed area drawing children both from nearby embassies and from the rather rundown hotels used by Social Services to house recent immigrants. This was, I suppose, the mid-Seventies, and there were quite a lot of Iranian refugees and families from Bangladesh although over the ten years I taught there the population was ever changing with a high percentage of children entering the school with very little English. While I did a bit of infant teaching, I mainly taught 7 to 9-year-olds. I think it's a perfect age group because they're still really enthusiastic about school and prepared to accept the teacher as a person rather than an authority figure."

"In 1987, my husband Alan and I came to Canada for the first time. My husband's an academic, law and sociology, and he was invited to teach at Ottawa's Carleton University for a year. Before we went back to England, Carleton offered Alan a permanent post. We thought about it and decided, ‘Why not?' Higher education was not a happy place in the UK at that time, and Carleton was really expanding."

"We went back home and gave in our notices and put our London house on the market. Unfortunately our timing couldn't have been worse. It coincided with a massive slump in the housing market, and houses became increasingly difficult to sell. To add to our problems, our house developed cracks in the front wall. London is built on clay, and following three very hot dry summers, the London clay had shrunk. A lot of these old Victorian houses were built without much foundation, and, as the clay shrinks, the house sinks and cracks. It took three years of monitoring before the insurance company would commit to specific remedial action. During this period, I was working as a supply teacher and flying over to Canada for holidays, but for one year I did a house swap with some friends from Ottawa who wanted to spend a sabbatical in London"

"Through working in schools, I'd become familiar with and impressed by a wide range of illustrated children's picture books and decided I'd really like to try to create one myself. Now, with a year free from teaching, was the time to do it. Not feeling confident about writing a story from scratch I chose to illustrate my own version of the Wide Mouthed Frog joke, nice visually because you can introduce a wide range of animal characters. I saw this as a picture book for youngish children, and I decided what I would do was make the frog perform various types of actions: she hops, she climbs trees, she jumps, she swims, she crawls, and she meets lots of different animals. Right from the start, I worked it out visually so there's a clue hidden in the preceding picture as to what the next animal's going to be. It was great fun doing it. My object was really to see if I could illustrate and maintain one character right through."

"I was using watercolours which I hadn't really had much experience with, but I love the brightness of the colours and the way the light shines through. The first illustration I did was a double spread of the frog leaving home. I had her sitting on a lily pad surrounded by her family, and I wanted to paint a background wash behind her. Now, the books will tell you how to do a watercolor wash, which is fine, but they nearly all tell you how to do it if you're going straight down an open page. It's quite different when they are things that you've to paint around. Water color dries very quickly, and, when it dries, it often leaves a line which is difficult to get rid of. Three times I meticulously drew out this picture and tried to paint an even wash. You learn as you go along, both techniques and how to overcome mistakes, but it's a lengthy process."

"It's interesting about style. When I look at the style of the artists I really like, they're often very freeflowing and spontaneous, but that is not how I paint at all. My illustrations are very detailed and busy. I think it's partly finding a technique that suits my current capabilities. Children's book illustrators, like Tenniel and Rackham and Sendak, have such a confident line, something at present I can only aspire to. I do like detail. I like putting in little visual jokes, clues, parts of story that aren't necessary to the basic storyline, but that add something extra." Laughing, Rosalind adds, "Also, the more space you fill, the less you have to put a wash in. I know from doing Medieval art history studies, they had this thing called horror vacua [horror of the vacuum], and I think I have that. I like pattern; I like color."

"I completed the wide mouthed frog although it took me over the year to do so. Then I started down the long trail to getting published. Luckily, the first publishers I approached in London gave me some encouragement, enough at least to keep me going through all the subsequent rejections."

"The Frog Princess is my first published book, but it is my third finished manuscript. The second story is about a family of vegetarian dragons who are sent a princess in lieu of a cargo of peaches. I'm currently rewriting this story, and I've also written a sequel. I've got increasingly interested in writing, although it's often a struggle to find the words to say something simply but interestingly. While supply teaching in London, I attended a writing course which was a great help. The most important advice was to just sit down and keep doing it."

"When I got over here finally in 1995, it was a time when they were actually laying teachers off in Ottawa, and, having had five years of supply teaching, I wasn't sorry. I decided I would carry on writing and illustrating."

Rosalind experienced an interesting form of cross cultural differences when she came to Canada and began sending her manuscripts to Canadian and American publishing houses. "In England, you have letter slots in the door, and so you can have any size manuscript coming back to you. Over here, there were these little tiny metal boxes attached to the wall, and no way could an illustrated manuscript be put into one of those. My first job was building a letter box to fit my manuscripts."

One of the Canadian publishers to receive Rosalind's illustrated manuscript was Kids Can Press. "I think I had a really lucky break. My manuscript hit the right spot at the right time.

Reflecting on the origins of The Frog Princess, Rosalind says, "I think it came partly from the wide mouthed frog. I really enjoyed painting the frog. And partly I think it came from Princess Diana and the idea that being a princess might better remain in the realm of dreams. So I proceeded to think of all the situations where life as a princess might pose problems for a frog. The biggest cause of the Frog Princess' problems resides in her inability to assess the context when she applies the ‘rules.'"

"The manuscript of The Frog Princess that I sent off to Kids Can was the completed work, text and pictures, and they accepted it as a whole. We, an editor and I, did a lot of work on the text, but the pictures were not changed except for the opening pages. The publishers felt that they wanted something stronger for the opening pages, and so I produced what you now see in the book. In the original of this particular picture, the royal family were all absorbed in eating and so, with the exception of the queen, they were actually all looking down. The editorial response was that they didn't want all these ‘closed' eyes. I tried to open eyes, but watercolor is not a medium that facilitates change, and it was not a great success. And so I was really glad that I had sent off completed pictures for the bulk of the book. I don't think I could have gone through that with every picture."

Another change that Rosalind did make involved the book's closing ballroom scene. "I have a great fondness for frogs, and I wasn't happy about having frogs legs on the platter. I had had sort of caviar-looking frog eggs, but the editors were right. It was too subtle."

Earlier, Rosalind had mentioned that one aspect of her illustrating style was her penchant for adding little visual jokes to her illustrations. In The Frog Princess, one such visual joke involves the fact that at the story's outset the frog has missed her breakfast. However, Rosalind has added something food-like, at least for hungry frogs, in various pictures, such as the fly in the carriage [p. 19] or the Prince's maggot fish bait [p. 25].

Another visual joke, as introduced on page 10, involved the frog's inability to find any "princess" shoes that will fit her large, frog feet. Observant readers will note that one of the frog's attendants is looking towards the shoes of a male servant, and when the readers next see the servant again [p. 16], his shoes are gone from his feet but appear on the frog's [p. 17].

In talking about her approach to illustrating, Rosalind says, "I tend to complete each picture before moving to the next one. Sometimes there are perspectives that I can't work out. For example, the picture on page 14 in which the Frog Princess is jumping down from the royal balcony took me ages. I actually made little sculpture clay heads of the prince, his bodyguard and the queen. Faces look so different from different angles. I've learned of the magic of mirrors. Sometimes a drawing just doesn't look quite right, but it ‘s difficult to see quite where the error lies. But viewing the drawing differently, through a mirror, magically jolts the perceptions and the problem is revealed."

Picture books, even fractured fairy tales, require research. "Out of interest, I borrowed a lot of library books on costume. Over five hundred years of medieval life, styles changed dramatically, not to mention differences between classes and between countries. I've actually mixed periods."

"I work a lot, but I guess I'm really slow. I go up to my desk every day except one day a week when I pot, a wonderful therapy. I rent space in a studio which is nice because I meet other people. I have a wheel and am hoping in the near future to buy my own kiln. It's good to have something constructive to do when I'm having problems writing or drawing. I have a lovely attic space where I work. I'm gradually acquiring all sorts of amazing things, like a scanner which will make sending off manuscripts easier. I used to photograph the art or get color copies made which is very expensive."

"I have four or five stories more or less written up. I find the writing quite hard in terms of creating language that is clear and simple and yet interesting. It's so easy for it to fall flat. My initial writing tends to be much too long winded, and I am getting better at ruthless cutting. As soon as I've got the story idea worked out, I play around dividing it into pages and thinking about the pictures and how I can have a different action or setting on each page. Right from the start really, I'm working the two things together."

Books by Rosalind Allchin.

This article is based on an interview conducted in Ottawa on April 5, 2002.